Sustaining League of Legends

With LoL esports still on the rise, the brain behind the UK's biggest competition explains how regional leagues can help keep its growth going.

Typically, an esport's popularity comes and goes. Real-time strategy franchise StarCraft, once the biggest esport in the world, has gone from filling arenas with tens of thousands of people, to being eclipsed by larger games like DOTA and Overwatch. Each of these games has had its moment in the spotlight, but no esport has managed to maintain mainstream appeal.

There is an exception, however.

League of Legends is a Multiplayer Online Battle Arena, or MOBA.

Since its release in 2009, it has become the world's most popular video game. In 2020, 115 million unique people played LoL, more than the combined populations of the UK and Spain.

So why is it so popular? The number one reason is the endless, fast-paced replayability of the game: no two games of LoL are the same. The second is its esports scene, with the game’s developer Riot Games putting its own money into producing tournaments, rather than relying on third parties.

These two main factors have resulted in LoL becoming the world's biggest esport. The 2020 World Championship received a peak concurrent viewership of 3.8 million viewers, with Europe’s premier esports league – the LEC – reporting record viewing figures for the 2021 Spring Split.

But there's a big question mark. With popular esports following a trend of popularity before falling into obscurity, many feared LoL would head down this path. However, with the esport still growing in popularity ten years on, there’s much to suggest it will be around in the long run.

An important factor in contributing to sustained success in any sport is the grassroots game. Players who aspire to be at the very top have a clear path in front of them to help them get there. LoL esports’ European Regional Leagues (ERLs) are a key component of this, and are only getting bigger.

"It's all about the story."

That's the attitude of Petter Sten, product manager of the UKLC, the UK's premier League of Legends competition and a key ERL. Sten is also responsible for the NLC, which sees representatives from the UKLC and Nordic regional leagues battle for a place in EU Masters.

He believes the "fixed" nature of the seasons, which are divided into a "spring split" and a "summer split" help these storylines to emerge.

“We need to understand the esport so that it’s not cannibalising on itself," he added. "Right now, we have a spring split, we have a summer split and we have some competitions in between.

"As a sports fan, you can relate to that concept; it’s very fixed. People can relate to the tournament system itself and what it means to compete in League of Legends. That’s the core foundation that it is resting on, and what has built the success and the continuity. People know what to expect, whether you’re a fan, a player or an aspiring pro.

"So that has also been a vehicle for players to get that confirmation of growth, and that’s one path to getting scouted and actually reach pro player status.

"Knowing what to expect each year is a very strong position to have as an esports publisher, rather than being left wondering: 'will there be another tournament?'"

The Import Problem

Over the years, western teams have been criticised for importing talent rather than fostering rookie European players developed in ERLs.

While each LEC team is limited to only two import slots, if each team were to max these out, 40% of players in Europe's top league would be Korean.

Due to the reliability of Korean esports player development, partially due to esports being funded by the government-backed organisation KESPA and South Korea's high-speed internet, bringing in an oven-ready Korean player has been seen as a much less risky option than relying on a complete rookie.

By 2017, 22% of the players in LEC were Korean. This was not just an issue in terms of restricting opportunities for European players; the overall result of importation was uninspiring. For example, Vitality’s Ha ‘Hachani’ Seung-chan was winding down his career, while H2k's Shin ‘Nuclear’ Jeong-Hyeon ended up using his opportunity in Europe to springboard a move to a top Korean team.

While they might ensure a team's survival, these imports would never help European teams compete with the big wigs at international level, nor develop European esports in the long-term.

Europe leads the way

However, the franchising of LEC in 2018, coupled with the emergence of ERLs as commercially viable entities, has given teams more flexibility, eliminating the threat of relegation and giving them the breathing room to take risks on European talent.

This has resulted in Europe achieving its best results internationally, with Fnatic reaching the 2018 World Championship finals and G2 Esports echoing the feat in 2019, as well as winning that year’s Mid Season Invitational. Both teams consisted entirely of European players.

This trend has continued, with only one Korean import in the LEC: Misfits’ Shin ‘HiRit’ Tae-min. The 2021 Spring Split champions, MAD Lions, debuted two rookies on their roster. Elyoya and Armut were complete rookies at the top level, while Carzzy and Kaiser both came through regional leagues in recent years. With ERLs supplying a constant flow of emerging talent, teams are no longer compelled to spend big on uninspiring Korean imports.

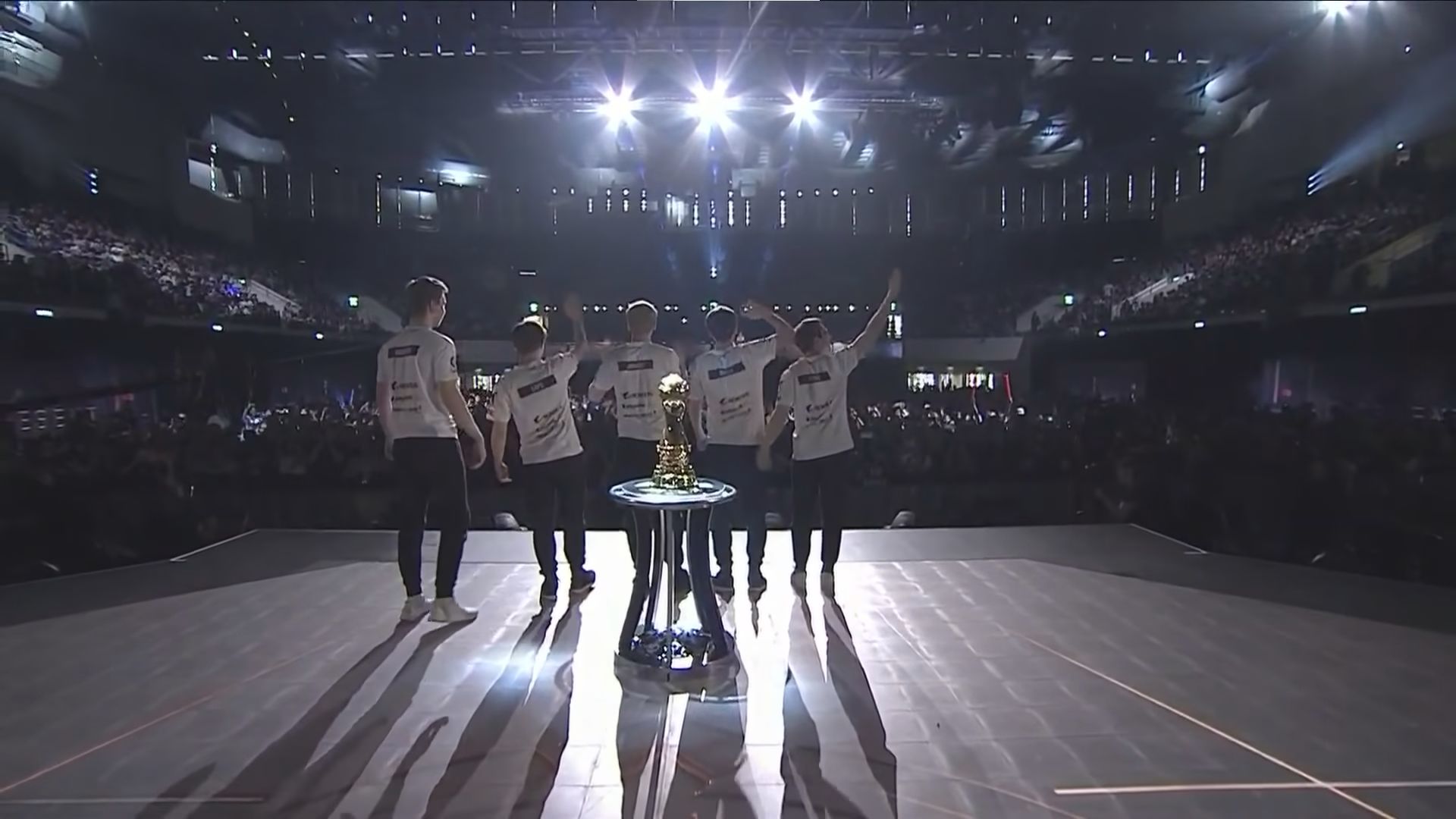

MAD Lions celebrate winning the 2021 LEC Spring Split.

“We had an LEC finals where we had a great deal of rookies, as an effect of Riot investing into structuring this system,” Sten explained.

"The European Regional Leagues (ERLs) have a purpose of being a talent factory. What you get in the ecosystem and circuit of League of Legends is knowing that you have a spring split, you have a summer split, and when you’re starting off you have connections in your region.

“What the NLC and UKLC offers is having that regional connection. You have the brands of the teams that are active in the region and also want to benefit this talent development for their own competitive gain.

MESDAMES ET MESSIEURS,

— Karmine Corp (@KarmineCorp) May 2, 2021

LA KARMINE CORP REMPORTE LES #EUMASTERS 2021 SPRING POUR LA PREMIÈRE FOIS DE SON HISTOIRE ET RÉALISE LE DOUBLÉ EUM & LFL ! 👑

QUELLE ÉQUIPE 💙#KCORP #BLUEWALL #KELAWIN pic.twitter.com/pT5vWev6QI

French favourites Karmine Corp won EU Masters for the first time in 2021, as they continue to develop some of Europe's hottest talents.

"But there’s also the option of selling these players on to an LEC team for a profit. That’s a big part of these organisations and a big part of the ecosystem.

“In the long run, these teams and leagues are the only physical thing that players, their families, their friends can see as tangible.”

LoL esports is also starting to permeate mainstream media. A key part of the UKLC's establishment is its broadcasting deal with the BBC, which Sten believes adds "legitimacy" to the competition.

"The BBC has been one of these platforms where we make it more approachable as a game and as a league, and it makes its way into the living room of the regular UK and Irish person.

"We have families watching. It makes a huge difference to players when they can say to relatives 'I’m playing in the UKLC and you can watch it on the BBC.' That’s a very powerful vehicle for us to grow the UKLC brand.

"We just want the brand of the UKLC to grow, but it has been a pleasure working with them; it’s been great for us as an organisation and the UKLC as a product."

There are whispers of Riot Games abolishing the rule that forces all LEC teams to have an academy team in the ERLs. These academy teams are intended to encourage investors to develop new talent, but with the success of ERL teams like Karmine Corp in producing new talents, this may no longer need to be made compulsory.

With an abundance of talent and stories to invest in, and viewership increasing with every game, ERLs are helping to keep LoL esports around for the long run.