Tell me where it hurts

living with chronic migraines

WHAT IS A MIGRAINE?

A migraine is a serious neurological condition which can have debilitating effects such as pain, nausea and visual disturbances. Migraine attacks can last several hours or several days and can be a whole-body experience.

It is estimated that around 10 million adults in the UK are affected, with 190,000 migraine attacks experienced every day in England.

Migraine is the third most common health condition in the world. It is more common than diabetes, asthma and epilepsy combined. Around one in five adults in the UK may be living with migraine.

COMMON SYMPTOMS INCLUDE:

- head pain,

- problems with your sight such as seeing flashing lights,

- being very sensitive to light, sounds and smells,

- fatigue,

- feeling sick and being sick.

The Migraine Trust, the only UK charity dedicated solely to understanding and helping people with migraine, estimate that up to 60% of the reason people get migraine is because of their genes. These genes make people more sensitive to changes in their environment such as lifestyle factors and triggers that can bring on an attack.

I spoke with Dr Peter Goadsby, 73, an Australian neuroscientist who, along with his collaborators, won the 2021 Brain Prize for their groundbreaking work on the causes and treatment of migraines.

He said: "Migraine is an inherited tendency to have headaches with sensory disturbance. It’s an instability in the way the brain deals with incoming sensory information, and that instability can become influenced by physiological changes like sleep, exercise and hunger."

INTERESTING FACT

Under the Equality Act 2010, if a person's migraines are severe enough, they are considered a disability.

MY STORY

I always imagined a life-shattering event would be big, apocalyptically big. I was wrong.

On the 13th of November 2020, the pandemic was still in relative infancy. The UK was in its second lockdown of the year. Supermarket shelves were empty. Zoom was in, and I was at home enjoying a respite from years of higher education.

My zoom call with friends went into the early hours, I had some sweets and a coffee to keep me going. That was it. My life-shattering event.

When we signed off, I had a headache and felt sick from the caffeine, sugar, and the long time in front of a screen.

The next day, I vomited five times on a beach walk. The next day, my head still like it was being split open by hammer and nails. And the next day. And the next. Months of near continuous vomiting, vertigo, the constant feeling like I'd drunk a whole box of wine to myself.

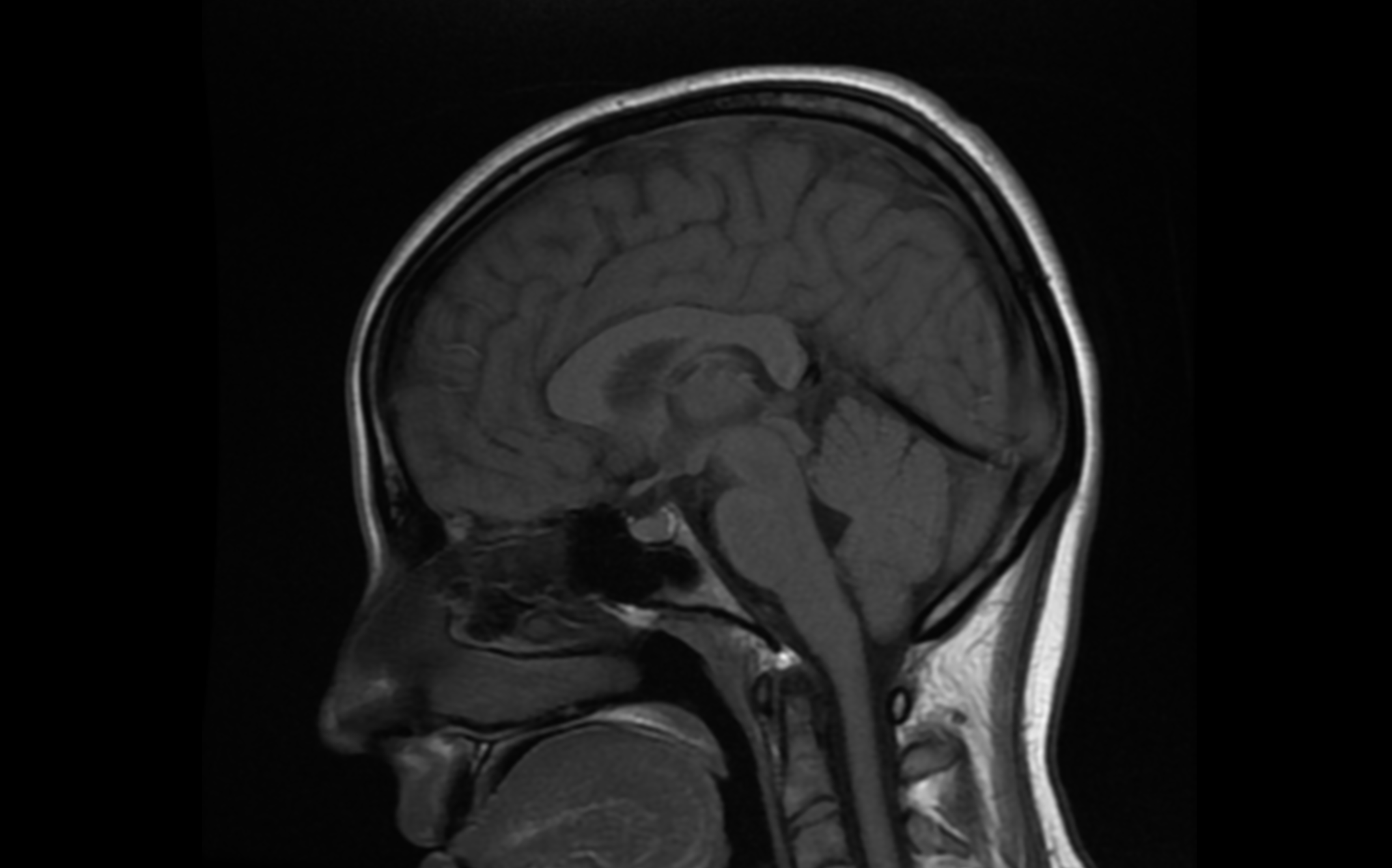

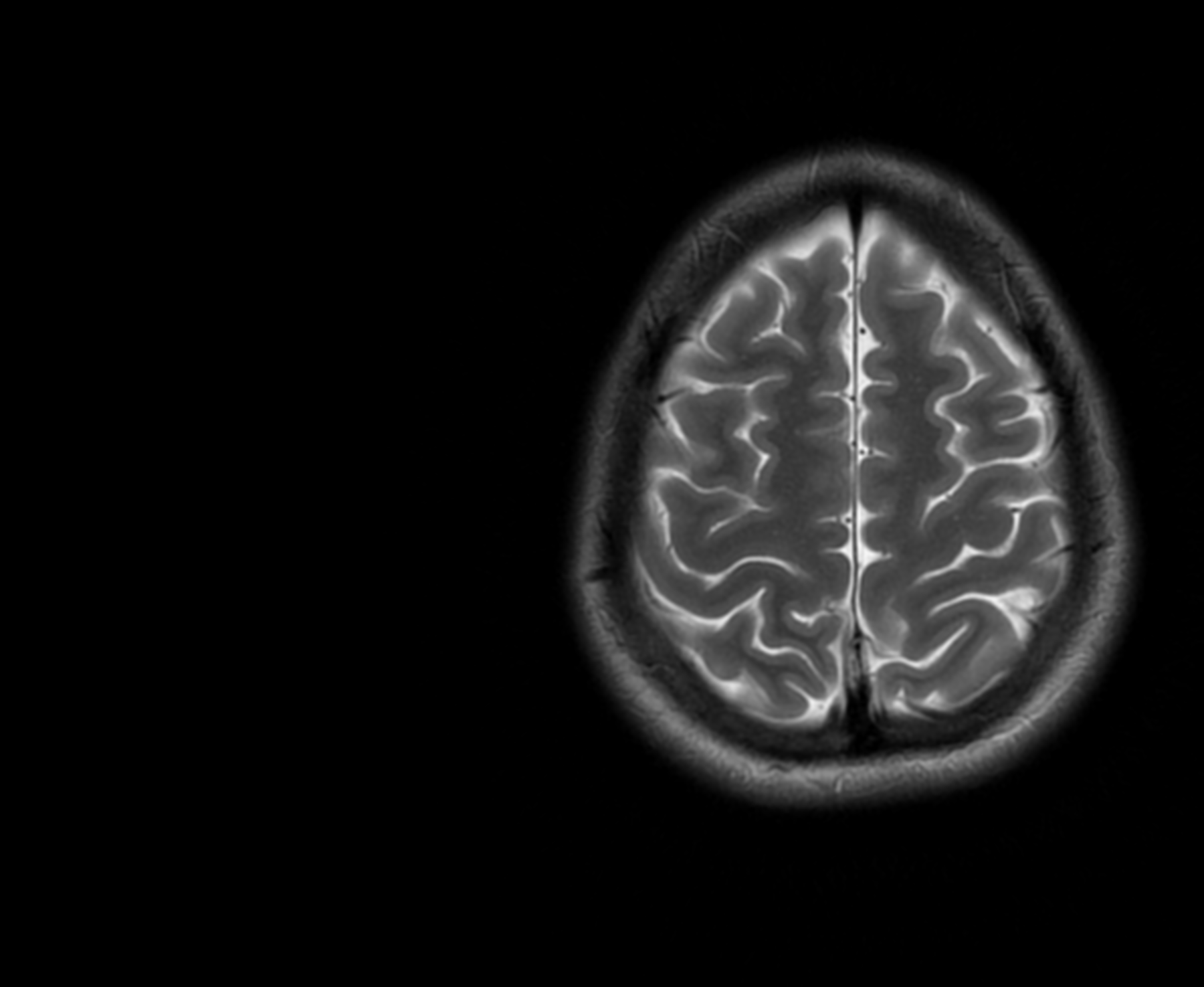

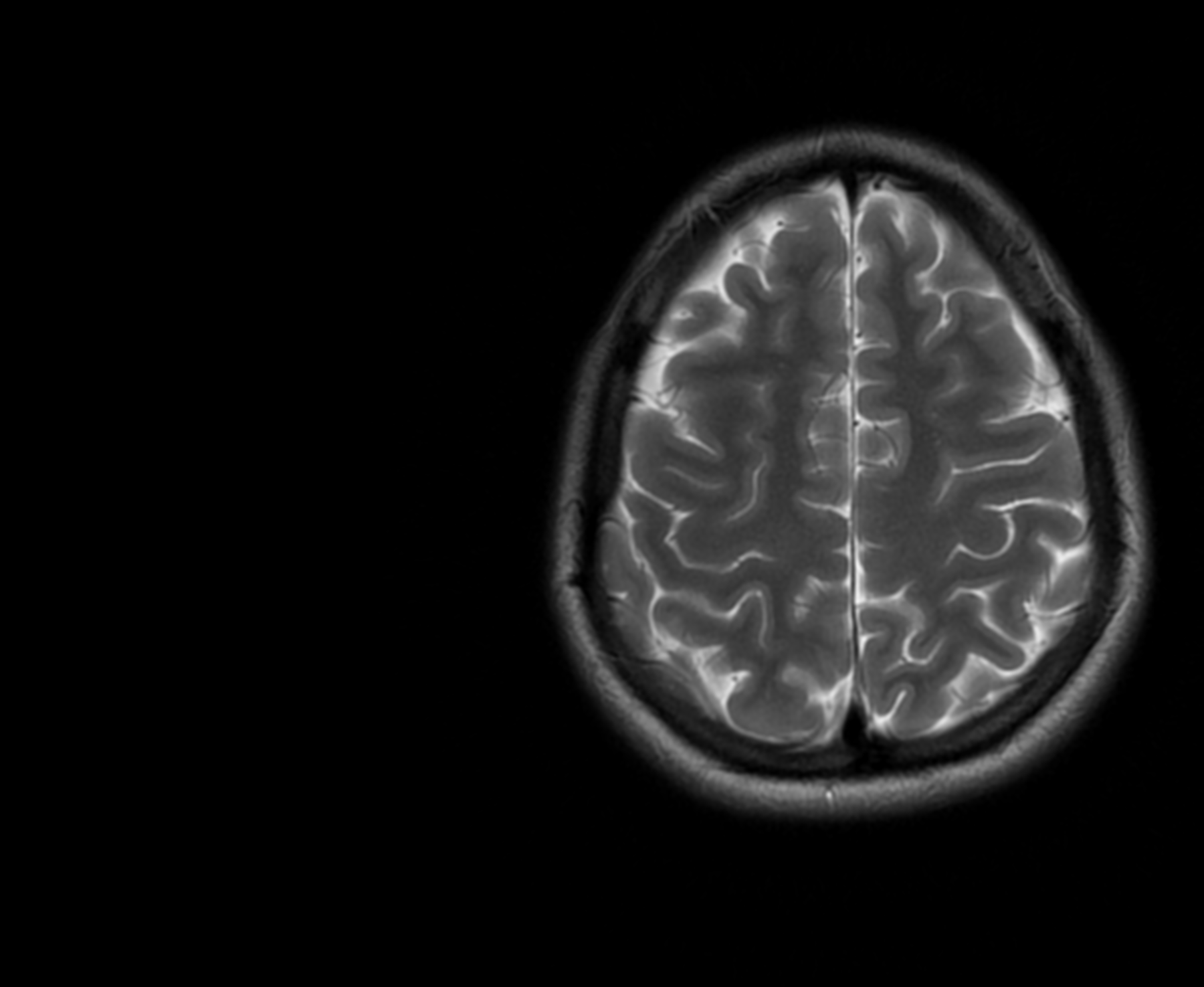

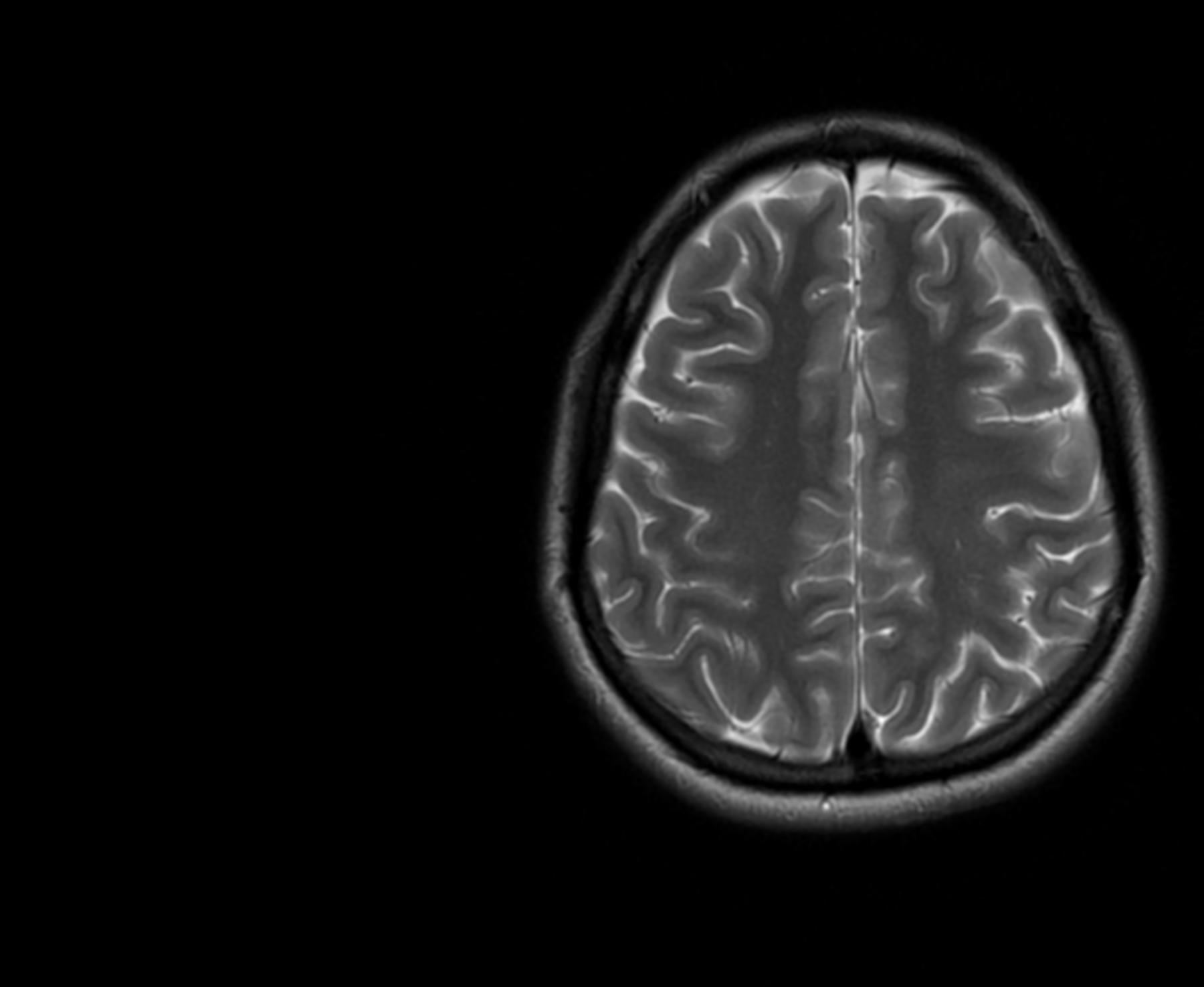

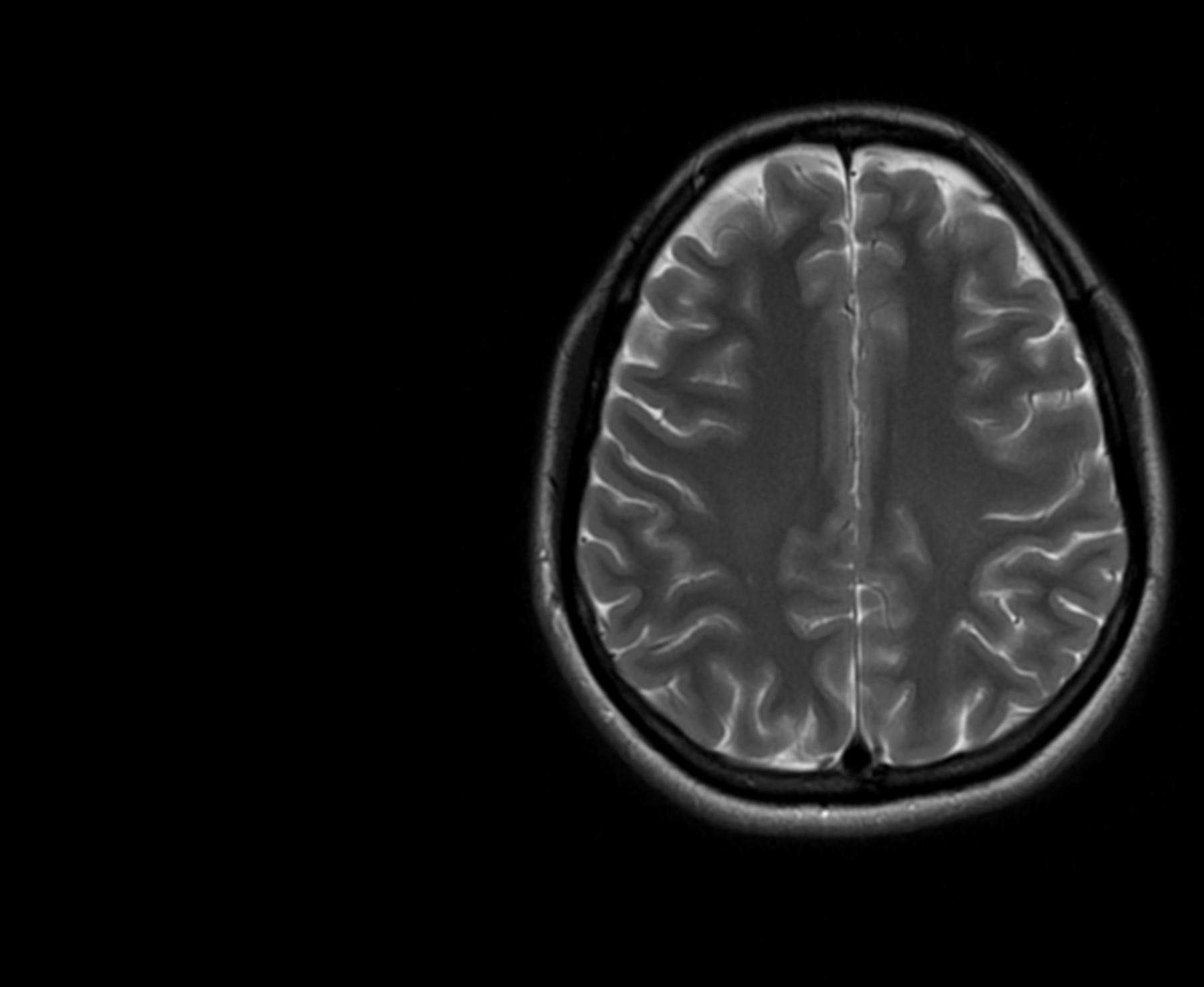

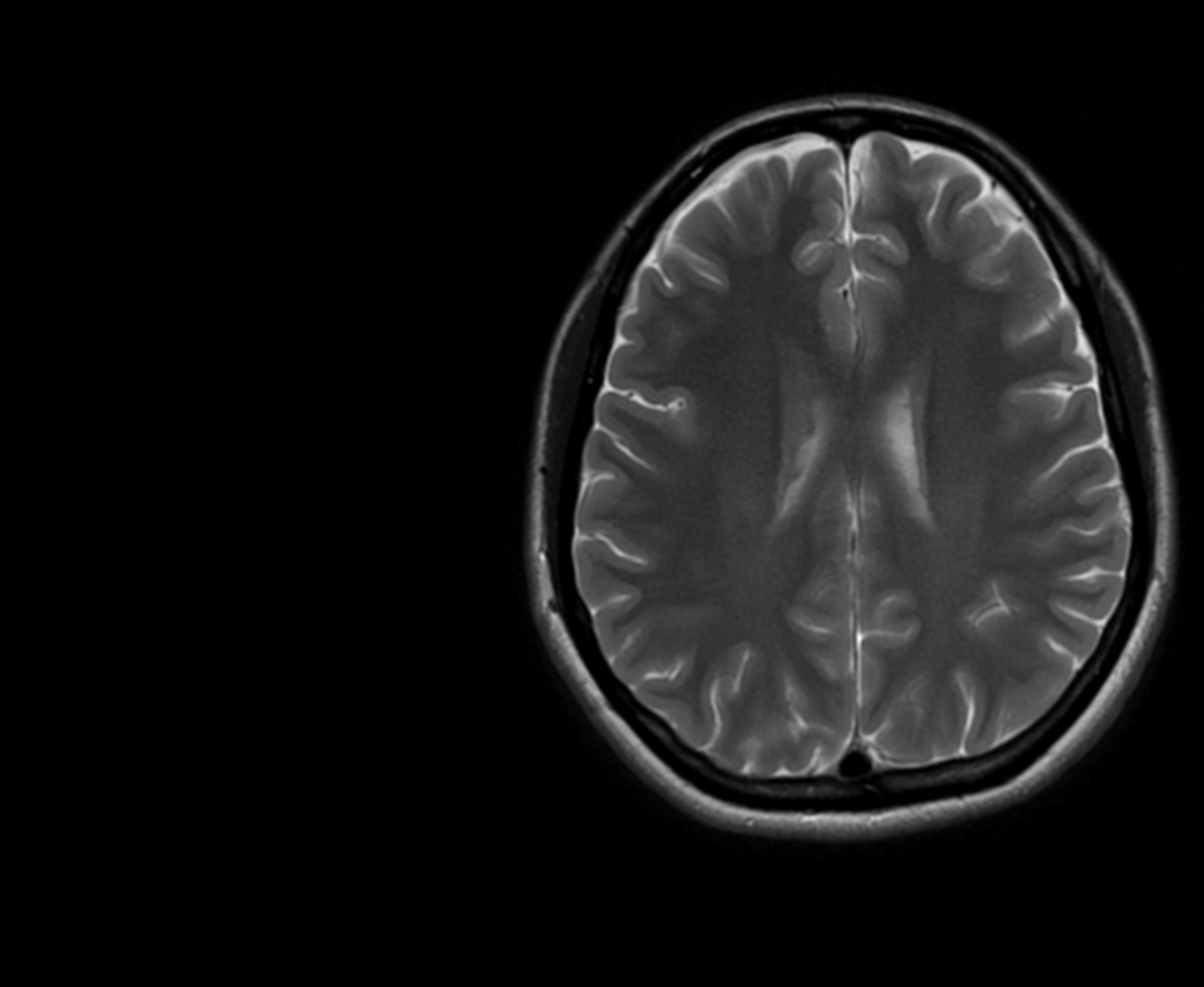

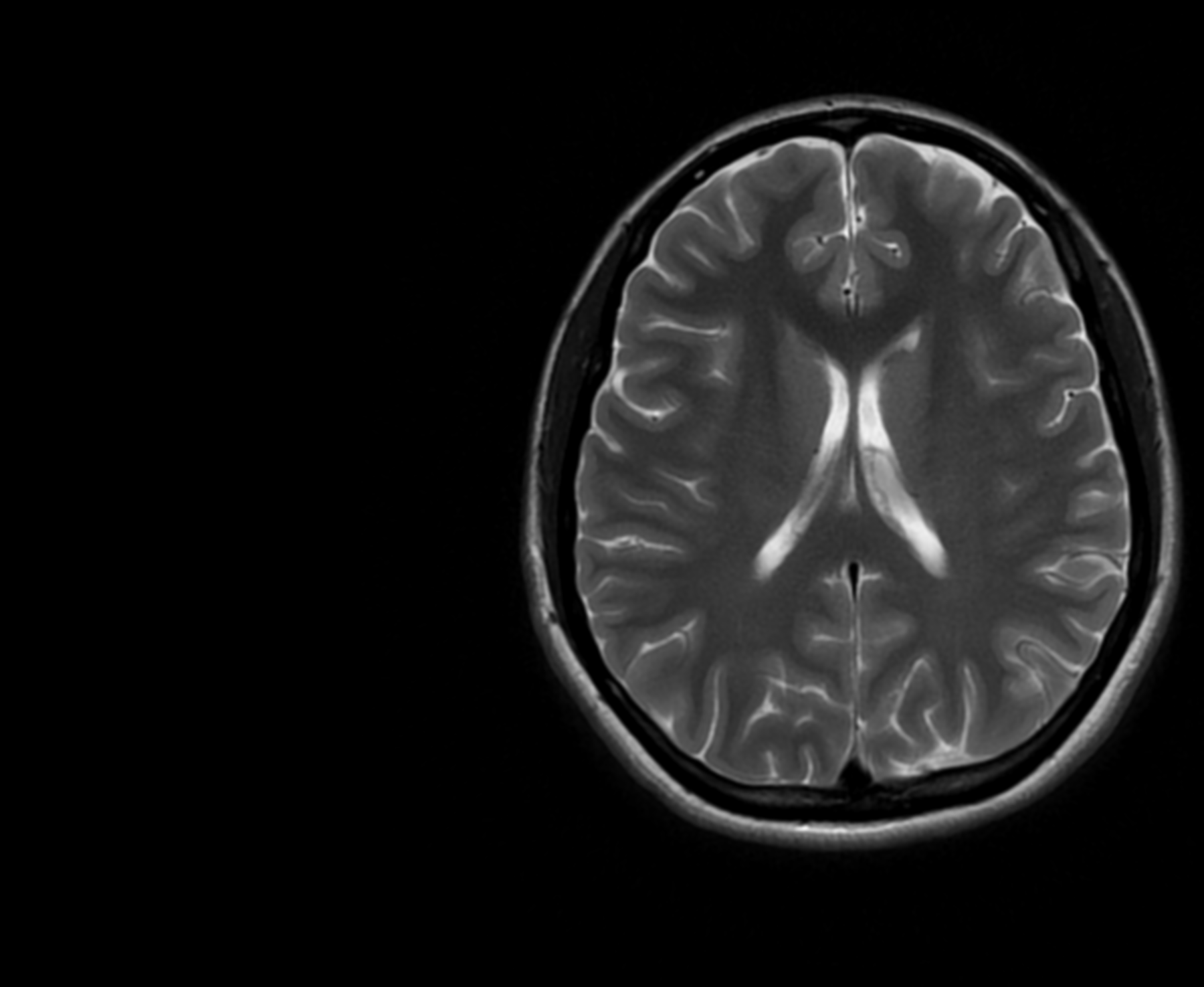

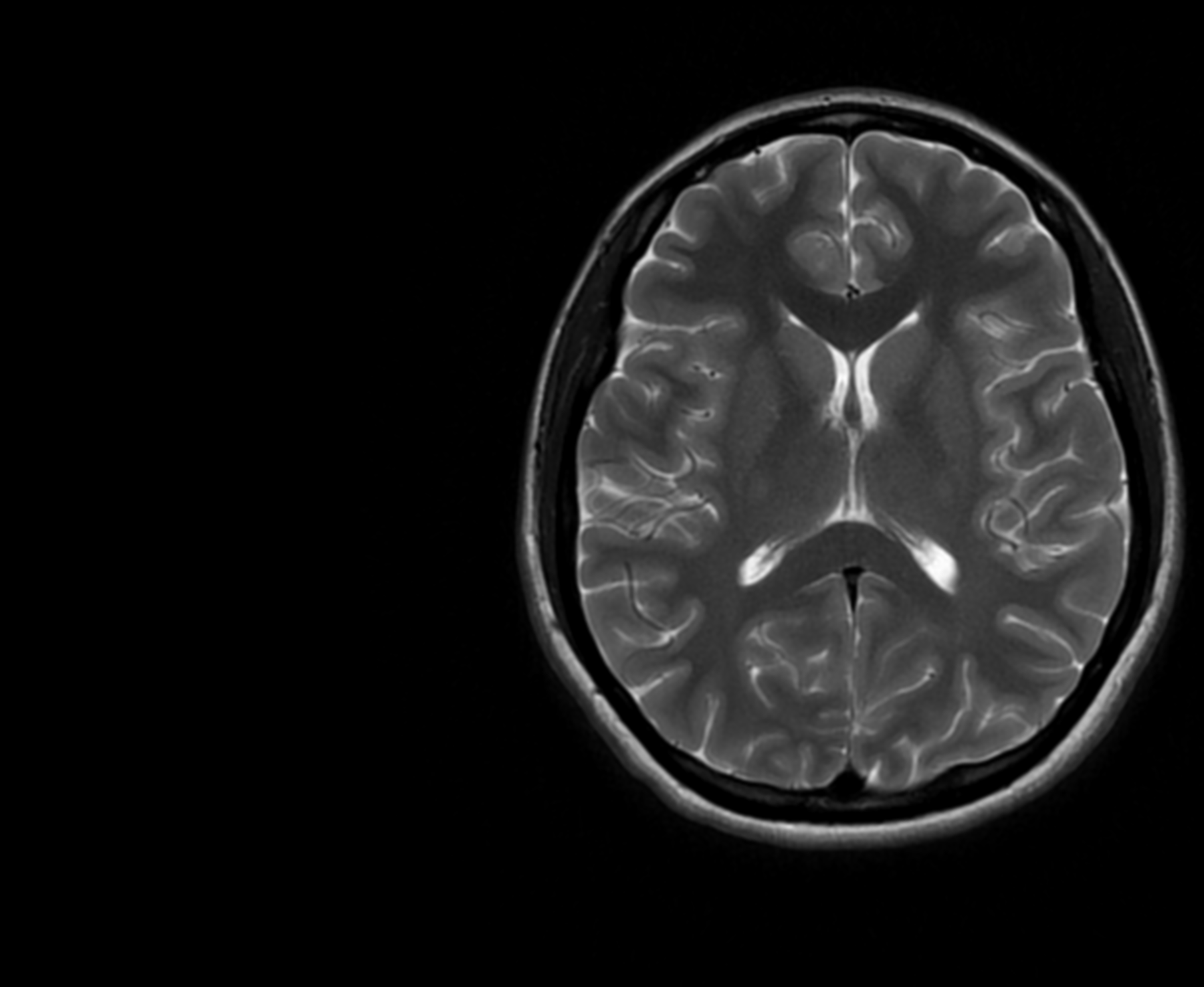

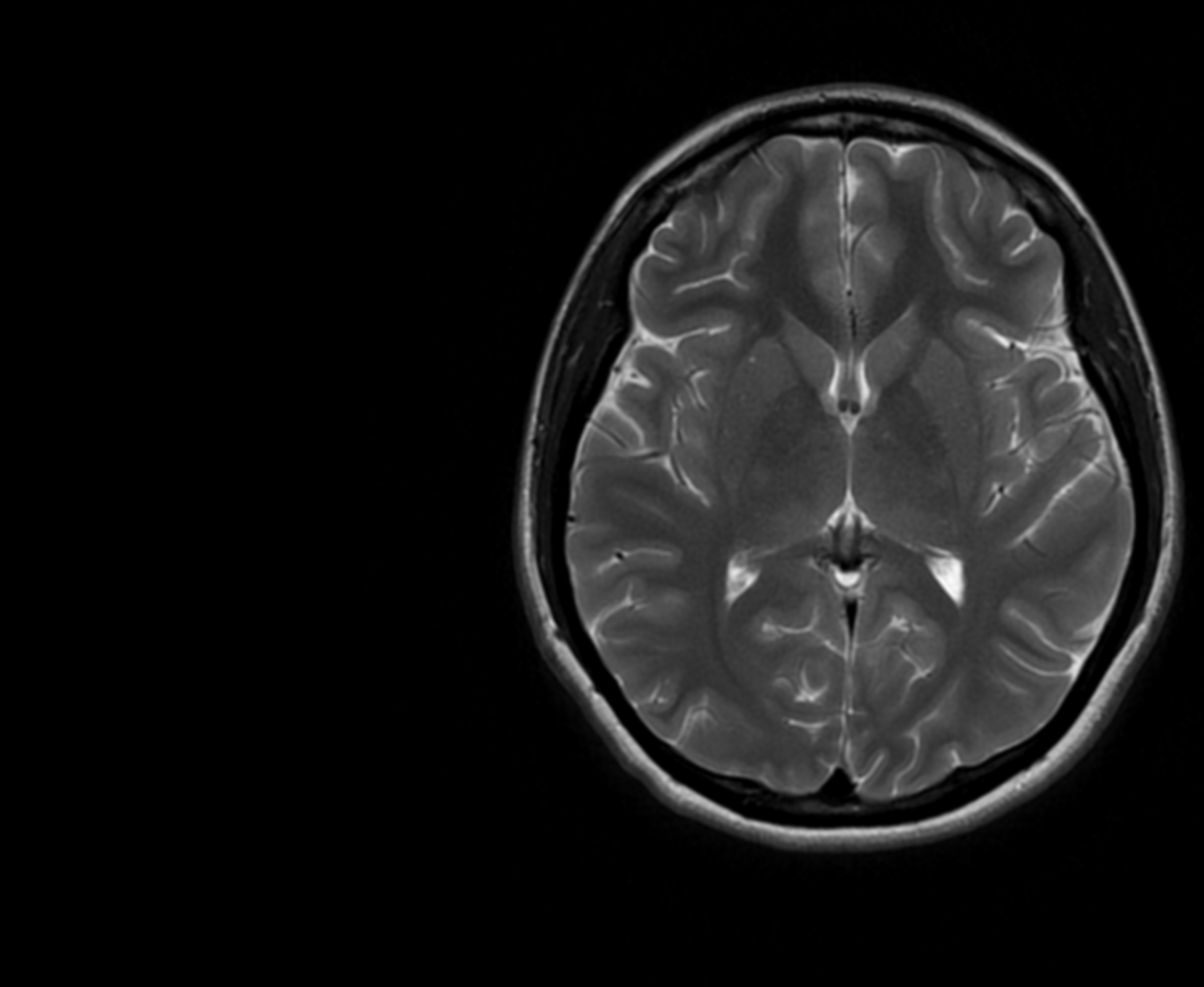

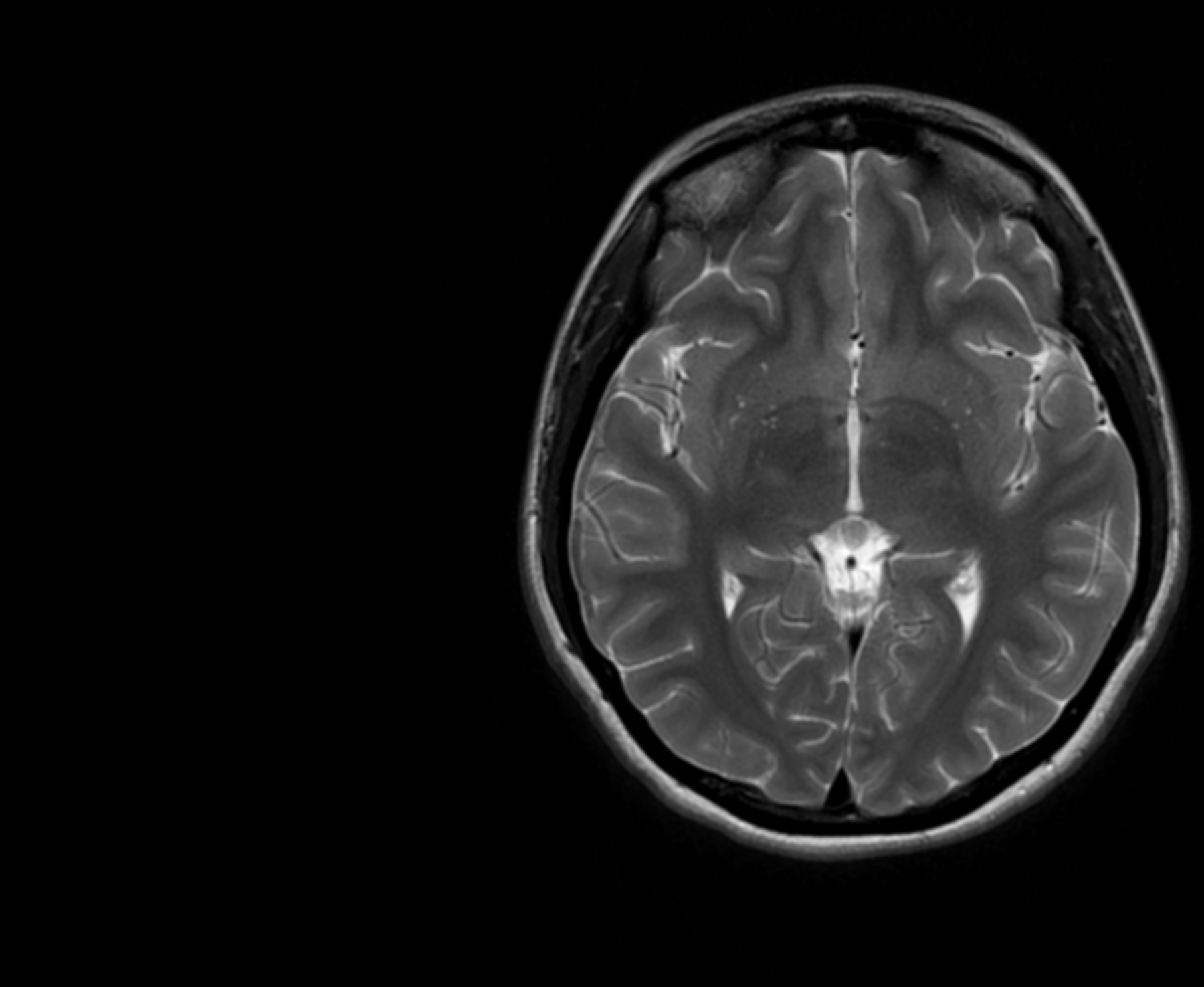

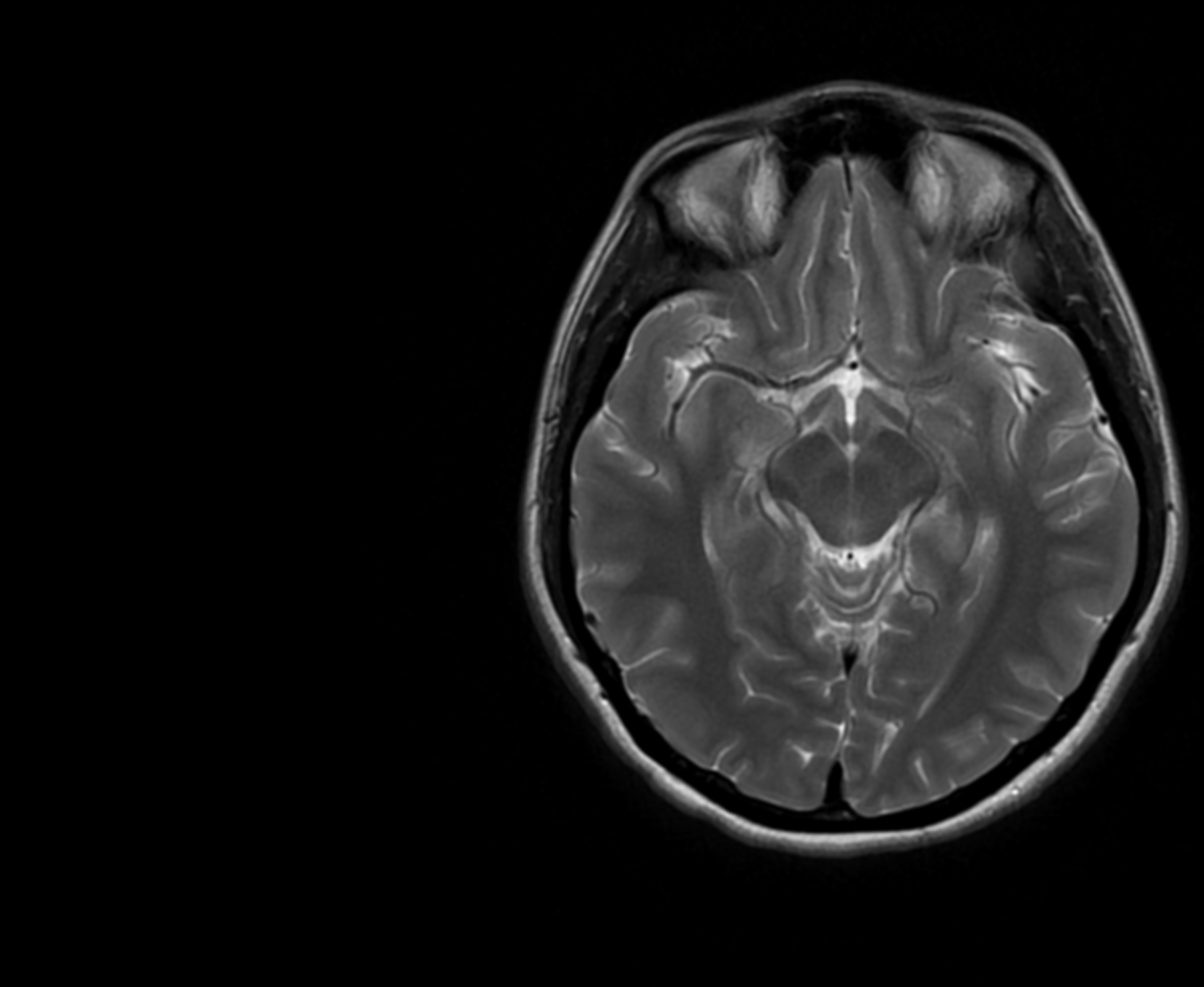

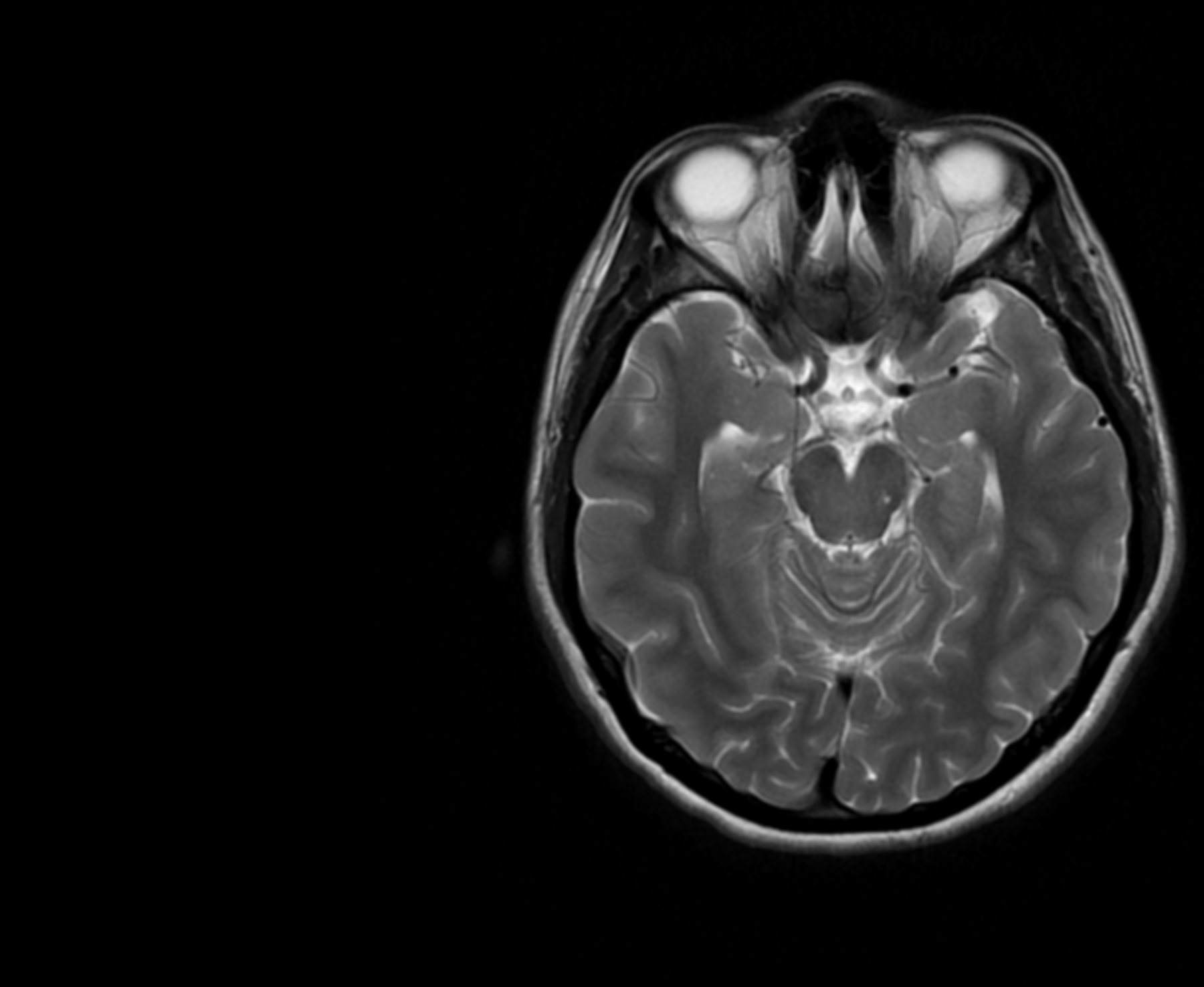

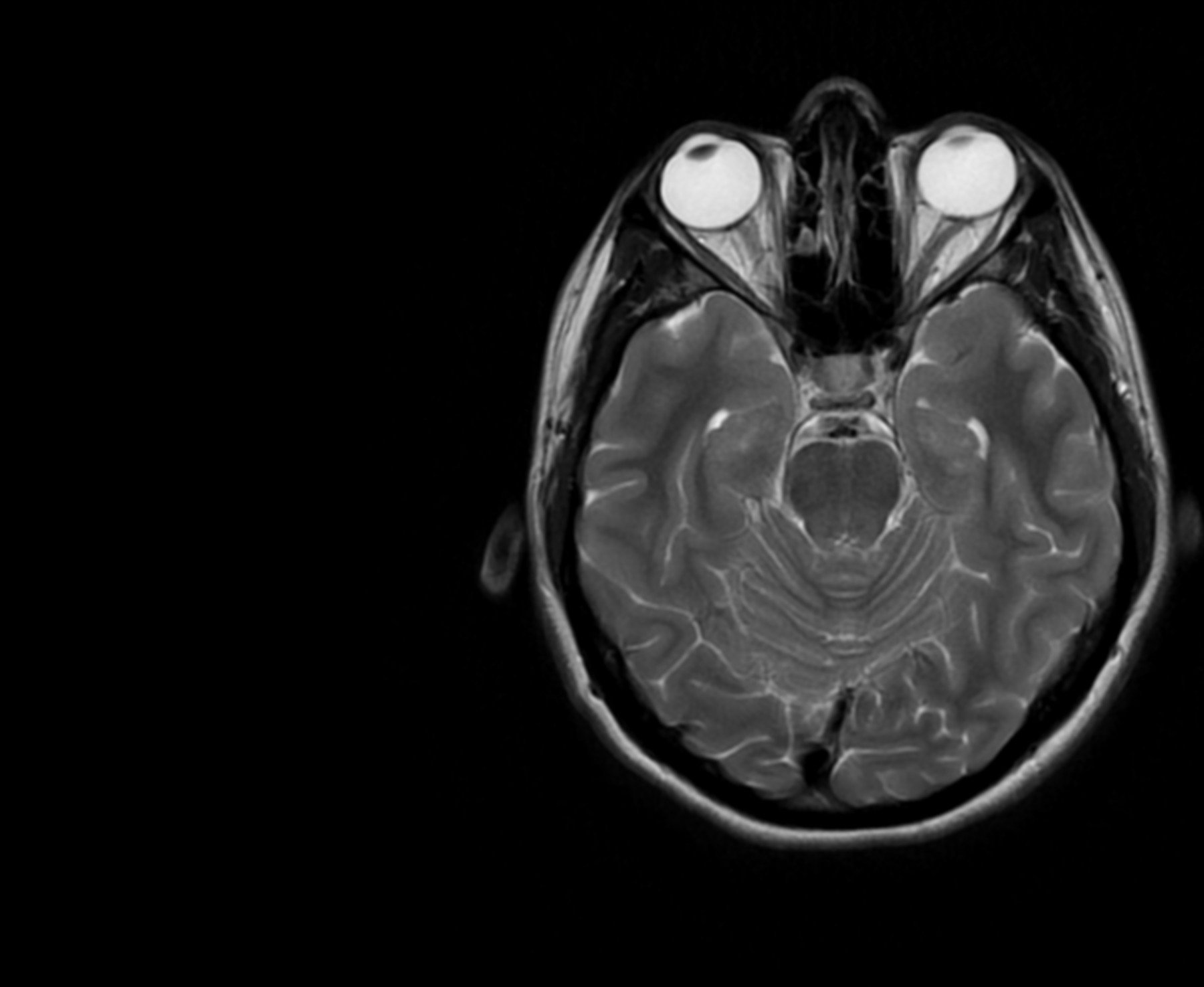

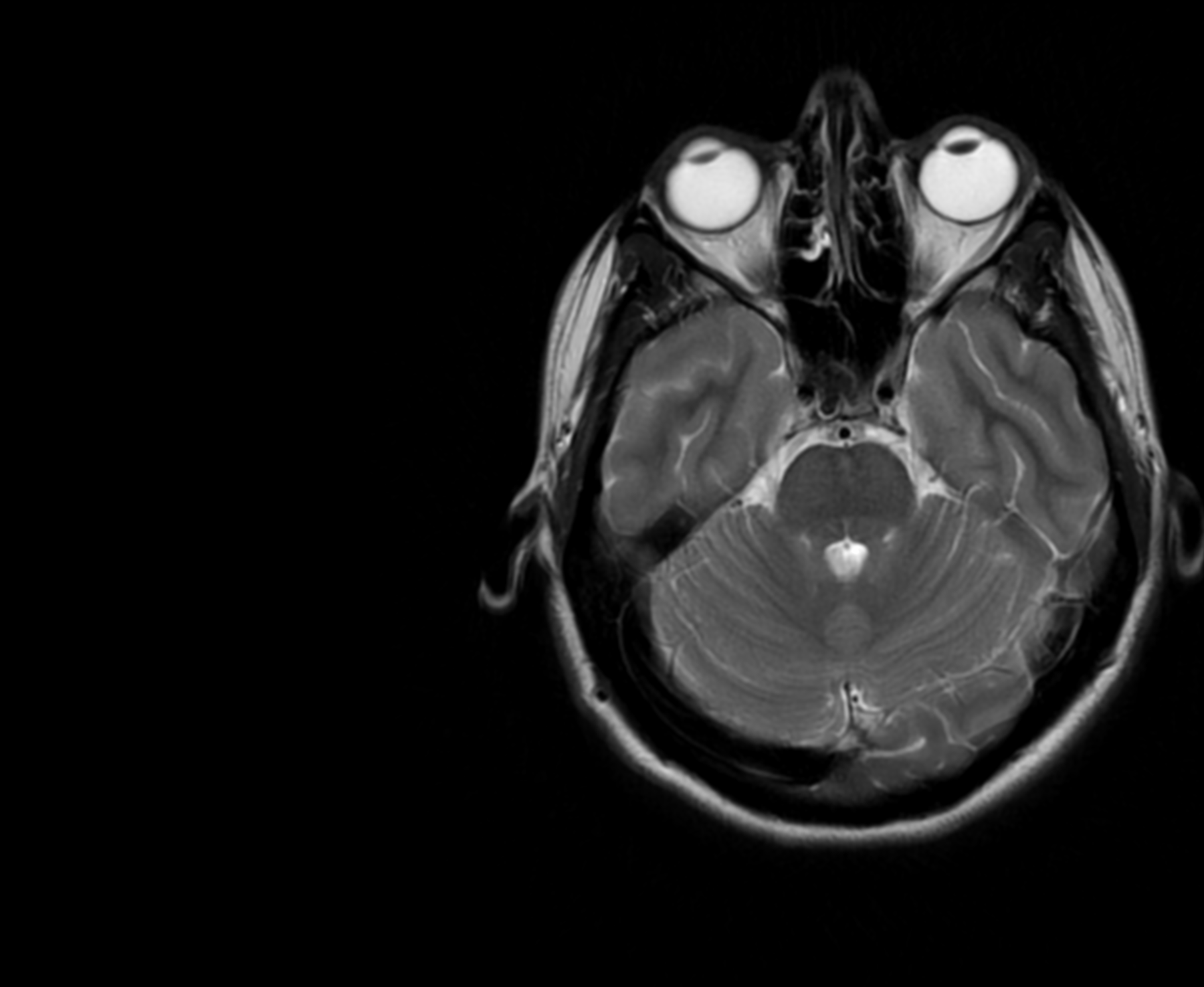

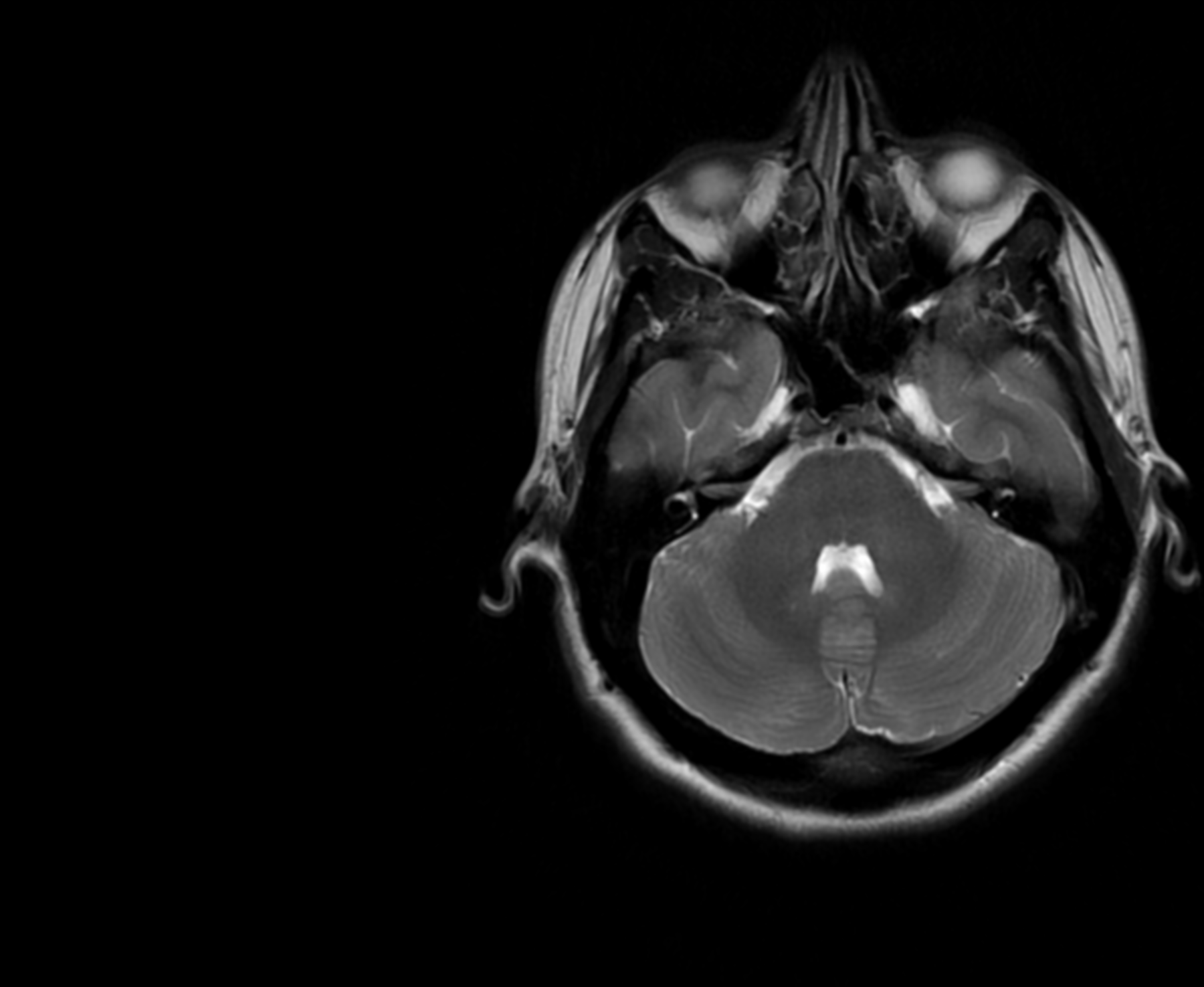

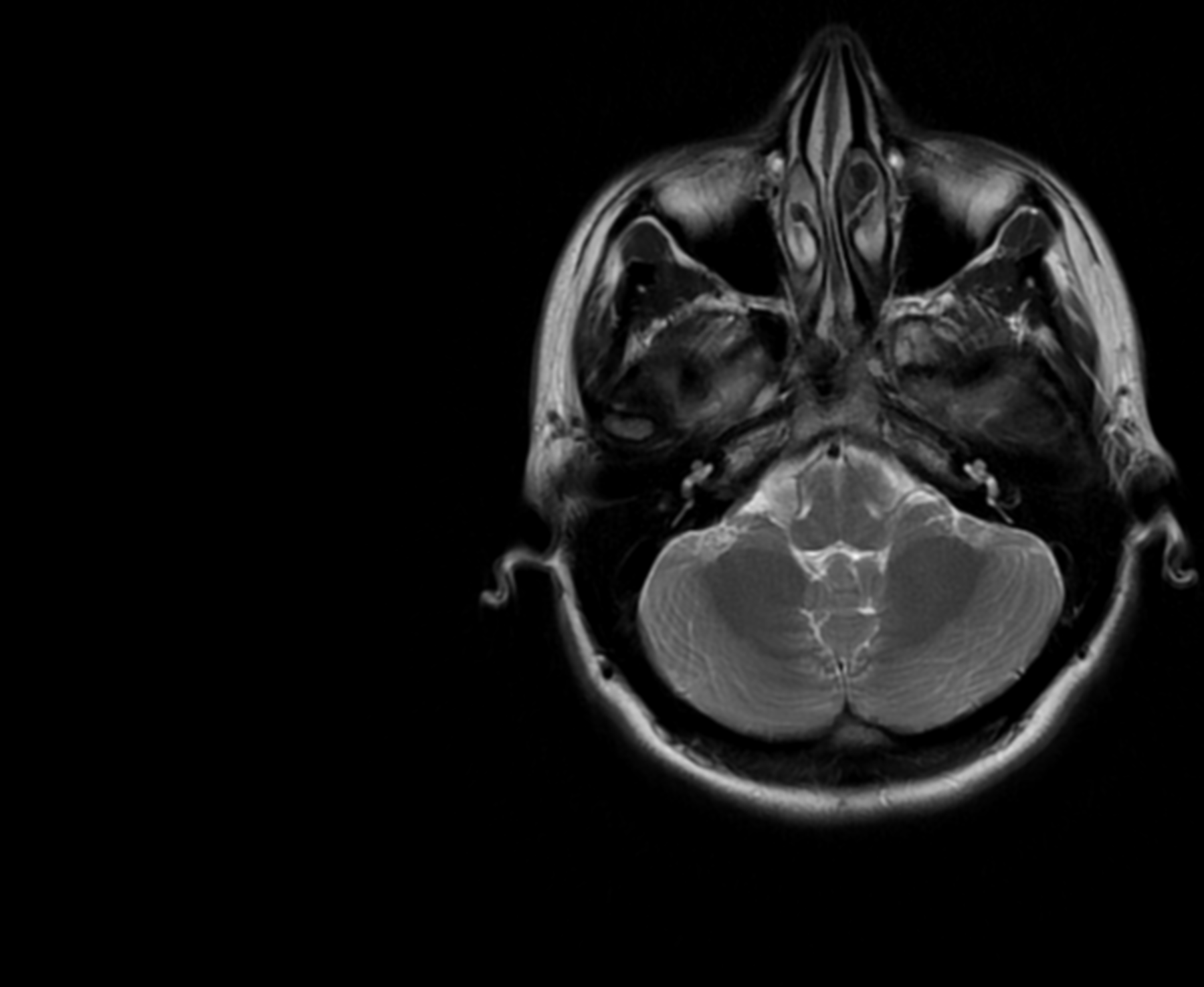

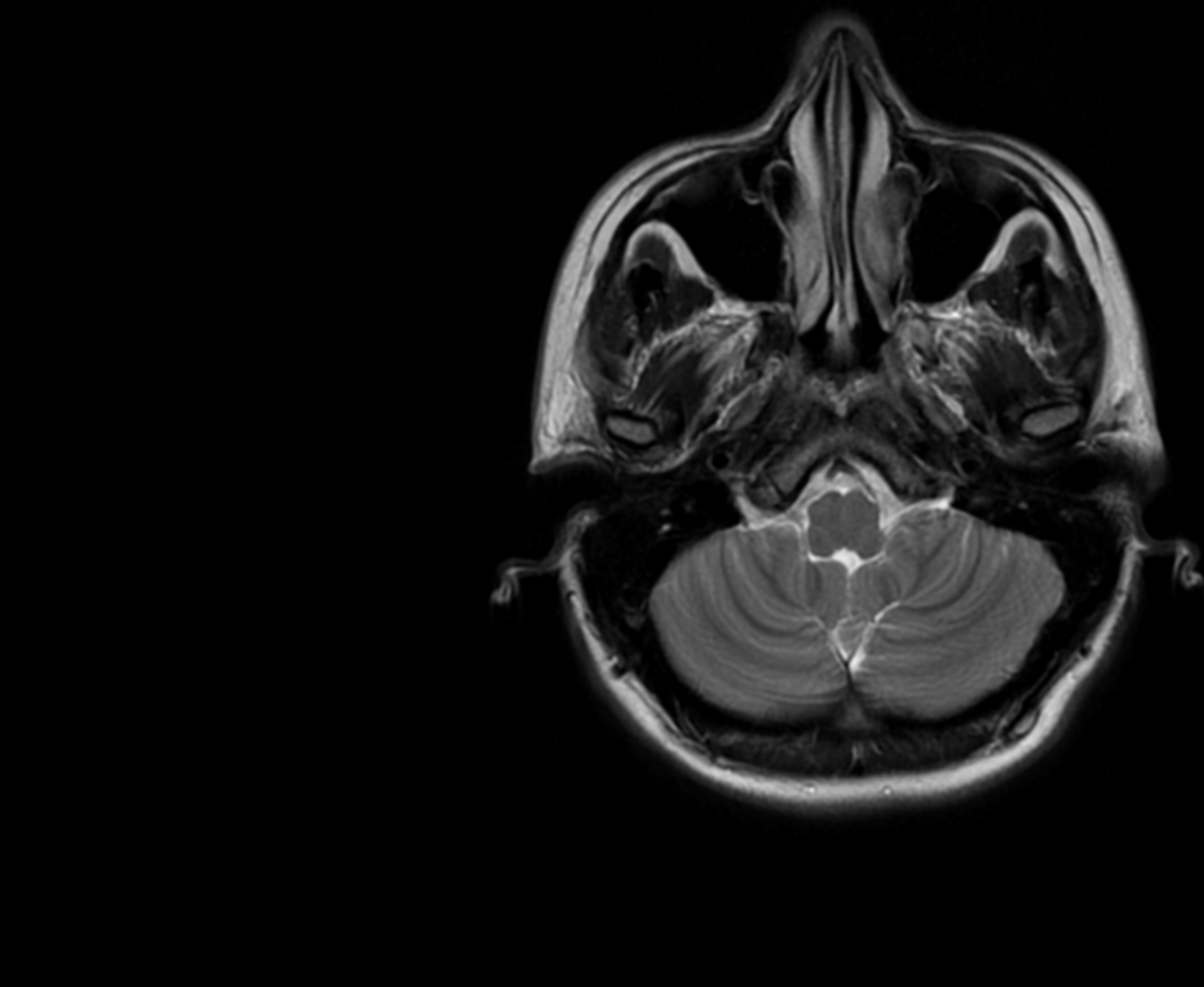

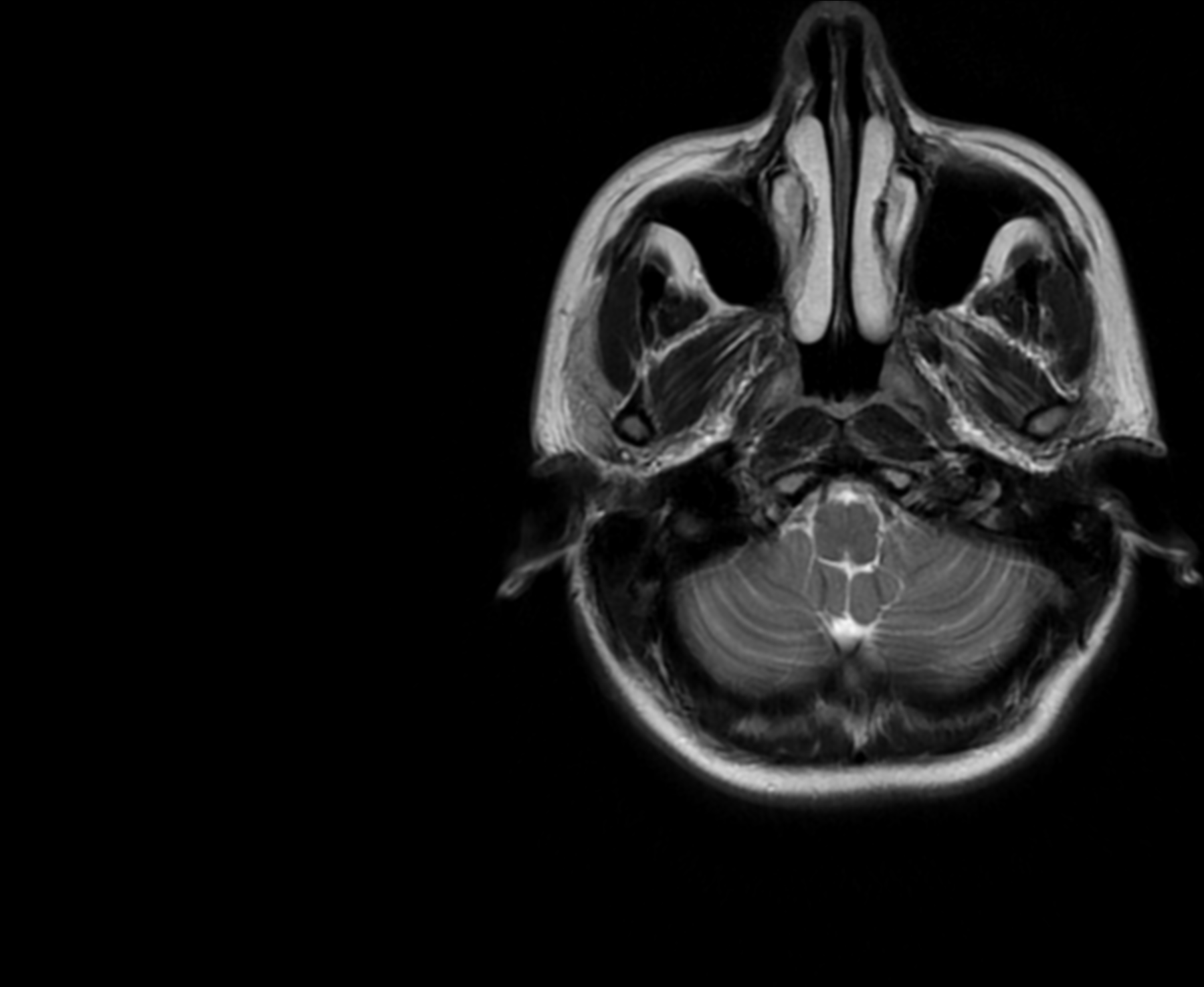

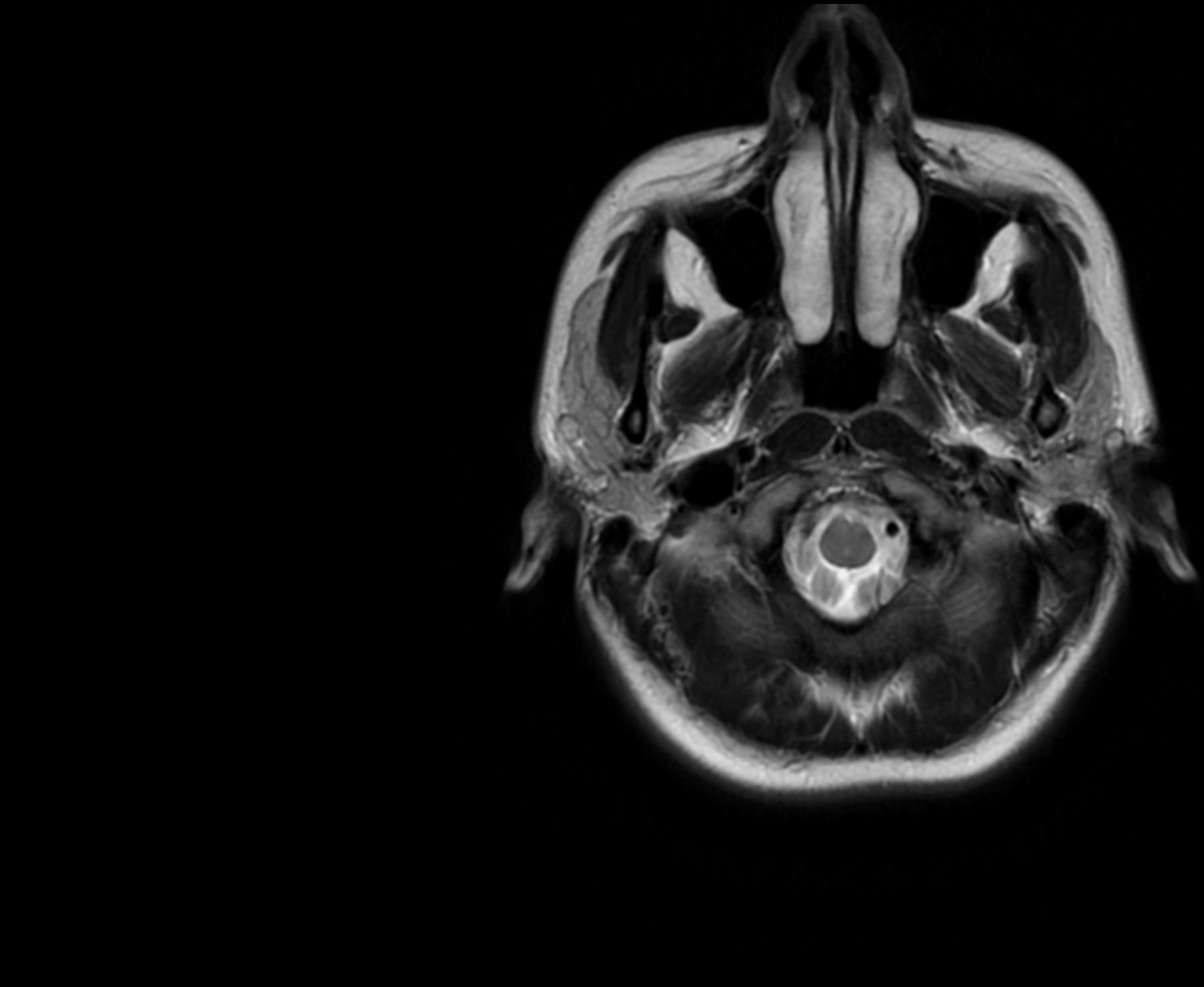

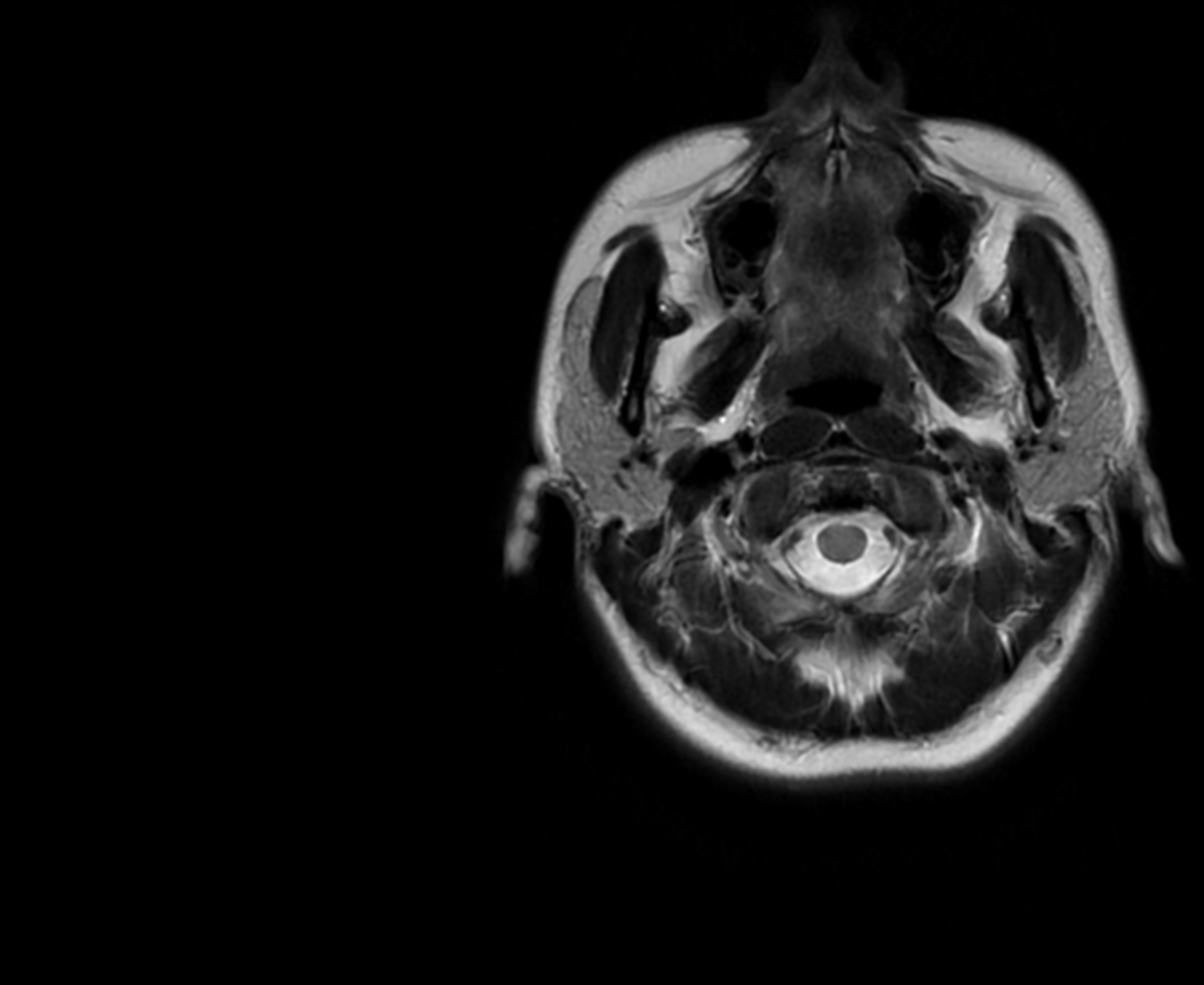

My mum worried it was a tumour (and as a nurse, her worry was hard to get). After an MRI scan, a four-day hospital visit, many tried and failed medications, I was diagnosed with chronic migraines on New Year’s Eve 2020; a neurological condition I may have to live with for the rest of my life.

Migraines are not new to me. I had abdominal migraines as a child, which, after puberty, became more typical. I experienced painful headaches, auras (a sensory disturbance which were a blurry blind-spot for me), nothing a quick nap couldn’t fix. These migraines were episodic, (episodic migraines are classified as someone who has less than 14 headache days a month), and I had very few of them.

But my chronic state was different (chronic migraines are classified as someone who has more than 15 headache days a month). It didn’t present like my previous migraines had. I had no aura, there were times I didn’t even have a headache. Instead, I was mainly suffering from nausea, vomiting, vertigo. My GP prescribed me a cocktail of drugs, none worked, and after a month of constant calls and visits, my doctor referred me for an MRI scan. It was all clear, but I still had no answer.

My doctor grew so concerned she called the hospital and got me on the list to see a medical consultant. But this was late December 2020, the hospitals were busy, and something went wrong with my referral. I wasn’t on any list. So, after a long wait, an A&E doctor saw me. The difficulty is, while I felt terrible on the inside, compared to everyone else in A&E, I looked fine. Migraines are invisible; they don't even show on scans. The A&E doctor asked if I’d drunk enough water. I said yes, a month into headaches and vomiting, I had made sure I was hydrated.

He said take some paracetamol and sent me home.

One week later I was back in hospital. This time I was admitted. I hadn’t been able to keep down any food for two days. I was kept in for three nights and was supposed to be seen by the neurology team, but they were all off sick with Covid. On Christmas Eve, I was told that if I could keep a sandwich down, I could go home. Thankfully I could, and I was released as a neurology outpatient. I still haven’t been contacted by the neurology team, two years later.

Luckily, as I was under 25, I was still on my parent’s private health insurance. We managed to get an appointment with a neurologist on New Year’s Eve and he quickly diagnosed me.

Over the course of the next few years I learnt that the majority of medications used to prevent migraines weren't designed to do so. Most migraine medications are borrowed from other neurological treatments, like anxiety and depression, and have been repurposed to treat migraines.

However, in the last five years, thanks to the ground-breaking research of Dr Peter Goadsby and his collaborators who identified CGRP, a protein released in the brain during a migraine attack which causes inflammation and thus pain, antibody injections have now been developed to target this protein and help prevent a migraine attack.

Under NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines, for patients to qualify for these specialist treatments they have to first try, and fail, three mainstream medications (it should be said that some patients find these medications to really help their migraines, I just wasn't one of them).

This process of trial and error can take a long time, but as I was being treated privately I could essentially fast-track the process. I would try one of the medications for several months and when it was clear it wasn't working, I could quickly change and try a new one. Even going privately, it took me over a year to qualify for specialised treatment.

If I'd had to go through the NHS it would have taken me a lot longer.

This shocked me. If I didn’t have the privilege of private health care, how long would I have been bounced from doctor to doctor until I got my diagnosis? How long to get treated?

Even with my diagnosis, I struggled with the shame of being chronically ill with an invisible condition. I worried that it wasn’t that bad. That I was exaggerating. When I was admitted to hospital, I was relieved. Not because I was going to be treated, but because it felt like proof that I was really ill. That people would have to believe me now.

For the majority of 2021 I was completely house, or rather sofa, bound. I experienced first hand the difficulty of getting diagnosed (and I'm one of the lucky ones) and of the little treatments available for migraines. Then in August 2021, I had a severe reaction to one of the medications I was taking for my acute nausea and vomiting. I developed a second neurological condition: tardive dyskinesia (a movement disorder characterised by uncontrollable, abnormal, and repetitive movements of the face, mouth, tongue, torso, and/or other body parts).

At the hospital, the nurse thought I had dislocated my jaw it was so twisted. Again, I was treated, and the effects have reduced but not disappeared. I now have to be very careful of what medications I take.

It felt like I was collecting life-long neurological conditions.

I'm now 27 and I never imagined I would end up having to live with a chronic illness. These years have taken me to some dark places so I wanted to write this article to share my experience and shed more light on chronic migraines and the millions of people in the UK living with them.

There are four stages of migraine:

prodrome, aura, migraine attack and postdrome.

Some migraine sufferers do not experience the aura stage.

STAGE ONE: PRODROME

The migraine prodrome is the very first stage of a migraine attack. This stage can last up to 72 hours. The symptoms can be physical changes and/or mental changes, and you might not even notice them. They can include:

- Feeling tired

- Yawning more than usual

- Food cravings

- Changes in your mood such as feeling down or irritable (high or low)

- Feeling thirsty

- Neck stiffness

- Passing more urine (wee) than usual

While subtle, it can be a good indicator of an impending migraine attack. The prodrome stage is the best time to try and stop the migraine setting by treating it with migraine medication, like triptans, or by non-medical methods, like sleeping in a dark room.

STAGE TWO: AURA

Around a quarter of people with migraine have aura. A migraine without an aura does not include this stage.

This stage can last from five to 60 minutes, and usually happens before the headache.

The aura of migraine includes a wide range of neurological symptoms. These symptoms include:

- changes in sight (visual disturbances) such as dark spots, coloured spots, sparkles or ‘stars’, and zigzag lines

- numbness or pins and needles

- weakness

- dizziness or vertigo (sensation of spinning and poor balance)

- speech and hearing changes

Some people experience memory changes, feelings of fear and confusion, and more rarely, partial paralysis or fainting.

Aura is the result of a wave of nerve activity that spreads over the brain (known as cortical spreading depression).

As this electrical wave spreads, the nerves fire in an abnormal way and this range of reversible neurological symptoms (aura) develop.

It is possible to have the aura symptoms without the headache, this is often referred to as ‘silent migraine’.

STAGE THREE: MIGRAINE ATTACK

This stage involves moderate to severe head pain. The headache is typically throbbing and is made worse by movement. It is usually on one side of the head, especially at the start of an attack. However, you can get pain on both sides, or all over the head.

Nausea (sickness) and vomiting (being sick) can happen at this stage, and you may feel sensitive to light, sound, smell and movement. Painkillers work best when taken early in this stage.

This stage usually lasts between 4 and 72 hours.

Interview with Dr Goadsby

Interview with Dr Goadsby

STAGE FOUR: POSTDROME

This is the final stage of an attack, and it can take hours or days for a drained, fatigued or ‘hangover’ type feeling to disappear.

(For me this was the strangest stage. I would feel incredibly hungover, as if I'd drunk several bottles of wine the day before even though I'd had no alcohol for months)

Symptoms can be similar to those of the first stage (premonitory). Often, they mirror these symptoms. For example, if you lost your appetite at the beginning of the attack, you might be very hungry now. If you were tired, you might feel full of energy.

Interview with Dr Goadsby

Interview with Dr Goadsby

KIM'S STORY

"Your life can change, you can be a normal person to a disabled person in a blink of an eye."

Kim Hughes' life changed forever 16 years ago in 2006.

As a teenager, Kim suffered with migraines but they disappeared only to resurface in her early thirties.

In 2006, Kim was a 33-year-old clerical officer for the Liverpool police when her suffered a stroke and developed hemiplegic migraines, a rare form of chronic migraines.

Hemiplegic migraines are characterised by their stroke-like symptoms; a migraine headache, aura, and weakness on one side of the body.

Kim, 50, gets very little warning of a migraine attack. First, she'll have an aura and a strange feeling in her head, then half of her body goes completely numb.

To this day, Kim does not know whether her stroke caused the migraines, or if her migraines caused the stroke.

She said: "There's always been that worry, after all these years, that I'll have another stroke."

Due to the stroke-like symptoms of her migraines, Kim worried every attack was another stroke. She was sent back and forth to the stroke unit, and had several CT and MRI scans, which revealed nothing. Her doctor said the headaches were just side effects of the stroke and kept sending her home.

Kim's story is a full of dismissal. First, a doctor dismisses her stroke as a migraine and then another doctor dismisses her migraines altogether.

It took Kim three long years to be diagnosed with hemiplegic migraines.

The mother of two young girls, aged eight and ten, Kim struggled with day-to-day life, sometimes struggling to get out of bed.

In 2006, Kim had only been married for three months when she had her stroke.

Kim said: "After my stroke, that was it then. He didn’t want to know after that. He didn’t want a sick wife.”

She was still working as a clerical officer for the police, but she said: "I was so ill, I had to have a bin next to my desk because I was throwing up every day.

“I don’t call it a life; I call it a half-life. It’s a half-life because most of the time you’re in a lot of pain and you can’t function.

“That’s what people don’t realise. Your life can change, you can be a normal person to a disabled person in a blink of an eye.”

On her fight to be diagnosed, Kim said: “You have to be persistent because you know there’s something wrong in yourself. You know your normal painkillers aren’t working.

"You know spending days in bed isn’t normal. You know being sick when you get them, isn’t normal. You know the loss of functionality in your life, isn’t normal."

In the end, Kim went to the Walton Centre , a specialised neurology hospital in Liverpool, and spoke to a doctor there. He wrote a referral letter to the Walton Centre where her condition was finally be recognised.

Kim explained: “I felt sad and lonely and unheard. Was it just me making it up? The doctors didn’t believe me even though I kept coming back with the same problem. Why didn't they take it seriously?

"You start to doubt yourself. Is it as bad as I’m making it out? Other people have migraines, but they don’t seem as bad. I just wish someone could look inside your head and see that pain, feel that pain.”

Kim started working for the police in 2001 but in 2014, after eight years of trying to work through her chronic illness, she made a difficult choice and was medically retired at the age of 41.

“I had to think, do I really want to retire?Never work again? The hardest thing is knowing I’ll never retire again. Work was my entire life.”

Instead of working, Kim dedicated herself to trying to help others suffering with migraines. She formed her own migraine group in The Brain Charity which became her second home.

“It’s easy to think you're on your own, that nobody understands knows this pain or understands what its like. But then you meet other people who know exactly what you’re going through. Who knows the pain. Somebody to give you a hug and say, ‘I know’.”

While chronic migraines can be a lifelong condition, and something Kim has been suffering with for 16 years, she hasn't given up.

She told me: “It really is hard but there is hope.”

LISA'S STORY

“I could go out with a full face of make-up but inside, I would be crumbling."

Lisa Mould’s life was changed by migraines long before she was diagnosed with the condition herself.

When Lisa was just 13-years-old she had to act as nurse to both her mother and father. Her father had just been diagnosed with cerebellar ataxia, a form of MS which affected his movement, speech, and ability to swallow. At the same time, her mum was diagnosed with migraines and often couldn’t leave her bed.

Lisa said: “To see mum so poorly and sick was horrible. It came down to me and my 10-year-old brother to look after mum and dad.”

It wasn’t until her mother was 53 that she received a full hysterectomy and thankfully, hasn’t had a migraine since. Lisa added: “She can drink till the cows come home now.”

Lisa with Mum, Antoinette

Lisa with Mum, Antoinette

Lisa, now 42, works as a Recruitment Consultant in Tamworth.

It took her 11 years to be taken seriously and receive proper treatment for her condition.

When Lisa started her period, she began having migraines every three months, but it was after the birth of her first daughter, Alice, at 27, that her condition became truly incapacitating.

Lisa explained what a migraine attack looks like for her: “It disables me. I can’t move, can’t lift my head off the pillow. I would be vomiting continuously, and even the tiniest bit of light was painful. The pain, it was so bad I’d just want to ram my head against a brick wall."

Lisa soon had another daughter, Rosie, and she explained how difficult it was to raise her children while suffering with migraines: “It was so hard, but I had to keep pushing through for the kids or else I would have been in bed every day.”

Lisa’s migraines are hormonal driven, triggered by too much oestrogen in her body. Due to the nature of her cycle, with both her period and ovulation, there would be no let up. Lisa would have just one week a month migraine-free.

She went to her doctors continuously for 11 years, only for her condition to be dismissed as general headaches and given non-prescription pain relief.

It took Lisa having a migraine seizure while on holiday in Dubai in 2019, for her doctors at home to listen. In the final days of her holiday, the left side of Lisa’s face completely dropped, she lost vision in her left eye, and was hospitalised for two days. Doctors feared she’d suffered a stroke and sent her for an MRI. Upon returning to the UK, Lisa’s doctors revealed years of migraines had caused significant scarring on the left-side of Lisa’s brain.

Lisa in hospital in Dubai

Lisa in hospital in Dubai

She was finally referred to a neurologist in 2019 and prescribed sumatriptan, a medication which is part of the triptan family. The triptans are designed to alleviate symptoms of a migraine attack but they are not a preventive treatment.

At this time, Lisa was taking up to eight medications a day. She said: “I felt like I was a pharmacy rattling around. My husband, James, said you can’t keep on like this.”

After being given a Prostap injection which stopped Lisa’s usual hormone production for six months, her neurologist diagnosed her with hormonal migraines.

The neurology referred Lisa to gynaecology, where she was told she qualified for a complete hysterectomy, but the waiting list was six years. Lisa was so desperate she decided to go privately instead.

In September 2022, after 15 years of truly disabling migraines, Lisa had a total hysterectomy, just like her mother before her.

Lisa’s only had one migraine since.

When asked what living with migraines was like, Lisa said: “When you say to people you have a migraine, they think it’s just a headache, but it literally disables the life out of you. It is like having a disability.

“I could go out with a full face of make-up but inside, I would be crumbling. Because it’s a condition people cannot see, it’s like a disguise when you’re actually crying out for help.”

Lisa’s advice to anyone reading who is suffering with migraines was this: “If I can help anyone, it would be to say keep on at the doctors and get your diagnosis. Don’t let them fob you off.”

MIGRAINES, A WOMAN PROBLEM?

Shame and a lengthy, difficult diagnosis seems to be characteristic of migraine sufferers.

I asked Una Farrell, Communications Manager for The Migraine Trust, why diagnosis takes so long and why ground in treatments have only recently been made.

She said: "The condition itself is invisible, so people can’t see it. And because everyone gets headaches from time to time so they might think they know what migraine is but they don’t.

"It's also not just that migraines are invisible, but in between migraine attacks sufferers are usually able to what everyone else can. It’s part of the issue of migraine visibility: sometimes someone presents physically well, and then when an attack happens its highly disabling."

Una added:"Because migraines affects women disproportionally to men I think that is likely to be a factor in its historic dismissal."

I asked Dr Goadsby the same, here's his response:

According to a paper published in the BMC, Bio-Med Central, migraine is three times more common in women than in men and is the 4th leading cause of disability in women.

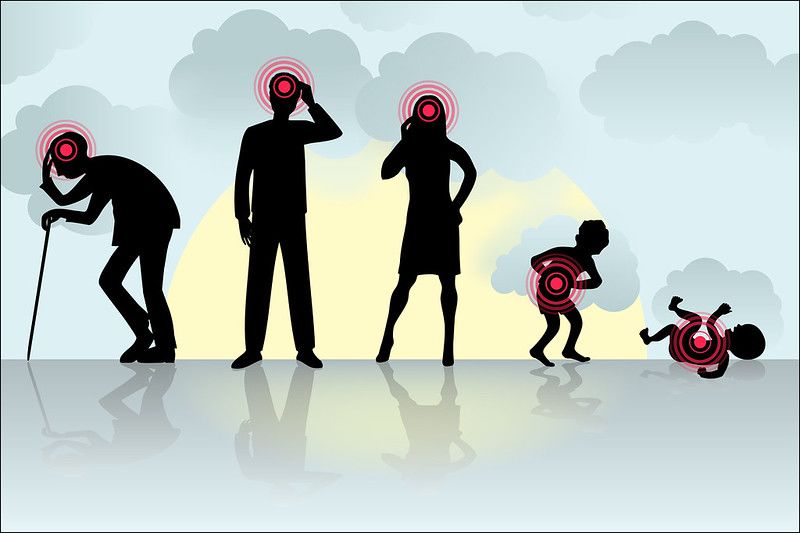

Below are the age and gender trends in the prevalence of migraine in the UK from data collected by the Global Burden of Disease Study in 2016.

The Migraine Trust said: "The dearth of research is a call to action, showing gaps that need to be filled in order to address this significant public health issue and achieve change for people with migraine."

The data shows that post puberty, the percentage of women suffering migraines is nearly double that of men.

Dr Goadsby explained that, as seen in the data, the prevalence rates for migraines are about equal between boys and girls, and that the disparity doesn't take off until menstruation with oestrogen cycling.

Migraines stop invariably, by about 85%, during pregnancy, and they also substantially drop off after menopause. It is the presence and changes of oestrogen which play an important role in turning on migraine biology.

When I asked him to explain further, he said: "The number of males and females who inherit the potential to have migraines, the genetic basis for it, is about equal. The activation of this basis happens more in females because of the higher levels and the cycling of oestrogen."

LIVING WITH MIGRAINES

Regardless of gender, migraine is a serious, invisible condition that can drastically change someone's life.

But Una Farrell is optimistic. She said: "It’s a really positive time for migraines, ever since the breakthrough five years ago, started by Dr Goadsby and his team, with preventive medication."

There are several places migraine sufferers and those wishing to understand the condition can go for help.

The Migraine Trust provide information and support directly to people suffering with migraine, through a helpline, live chat, and online tool kits. But it also raises awareness of the problems in migraine care, like slow diagnosis and people falling out of the healthcare system due to poor treatment. It also wants to raise awareness of the condition in schools and the workplace, while also funding migraine research.

UNA'S ADVICE TO MIGRAINE SUFFERERS:

- "If you want to access these new treatments, you need to make sure you are seeing a headache specialist, not just a neurologist."

- "You should start a headache diary as soon as possible. This will really help with the treatment process."

- "It’s really important people understand the migraine stages so they don't falsely identify food cravings as triggers. That the pain of a migraine is actually the third stage of an attack, so the attack has already begun, and that the postdrome, that hangover feeling where you can feel depressed and emotionally raw, is still very much part of the migraine attack."

UNA'S ADVICE TO PEOPLE WHO CAN HELP MIGRAINE SUFFERERS:

“It’s quite simple what needs to be done to make things better for migraine sufferers.

"Take migraines seriously."

She added: "Your employer can’t cure your migraine, your family can’t cure your migraine, you can’t cure your migraine, but there are things people can do to make life easier and reduce the obstacles people with migraines face.

"Give reasonable adjustments, ensure they get breaks, have access to water, things like that. These are very small changes that can make a big difference."

I put the same question to Jo Bird, the Equalities Officer and Research and Policy Department of USDAW, a union dedicated to protecting their members in the workplace.

This was her response:

USDAW is there to make sure those suffering with migraines can continue to work fairly and equally.

Organisations like The Migraine Trust, USDAW and The Brain Charity are there to help the people, and those around them, to learn to live with migraines.

FEATURED IMAGE CREDITS:

- All MRI pictures featured are my own.

- First non-MRI picture featured: 'woman with head in hands': Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) Jose Navarro.

- Second non-MRI picture featured: 'graphic of migraine at all ages': Migraine Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) JoanDragonfly.

- 'Woman lying in bed': Shutterstock.

- Kim Hughes' images: The Brain Charity.

- Lisa Mould's images: Lisa Mould.

- All other images: Shutterstock.