THE ART OF THE STEAL?

The impact of artificial intelligence on London's art world

Good artists copy, but great artists steal, said Picasso. At least, according to The National Gallery. Fittingly enough, it’s possible Picasso stole the famous aphorism from others before him.

Poet T.S. Eliot, philosopher C.E.M. Joad, critic Lionel Trilling, composer Igor Stravinsky, and novelist William Faulkner have been cited as originators, each having some variation of the phrase, all of them imparting a common essence (Eliot says: “great writers steal…”, Stravinsky says: “good composers steal…”, and so on).

That said, the earliest version of the aphorism can be found in an 1892 article titled “Imitators and Plagiarists”, published in The Gentleman’s Magazine, written by W.H. Davenport Adams.

Lauding the literary authenticity of the then-recently deceased poet laurate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Adams writes:

“Of Tennyson’s assimilative method, when he adopts an image or a suggestion from a predecessor, and works it up into his own glittering fabric, I shall give a few instances, offering as the result and summing up of the preceding inquiries a modest canon: that great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil.”

At this point, you may (quite rightly) be asking: what does any of this have to do with AI-generated art?

Quite a lot, actually.

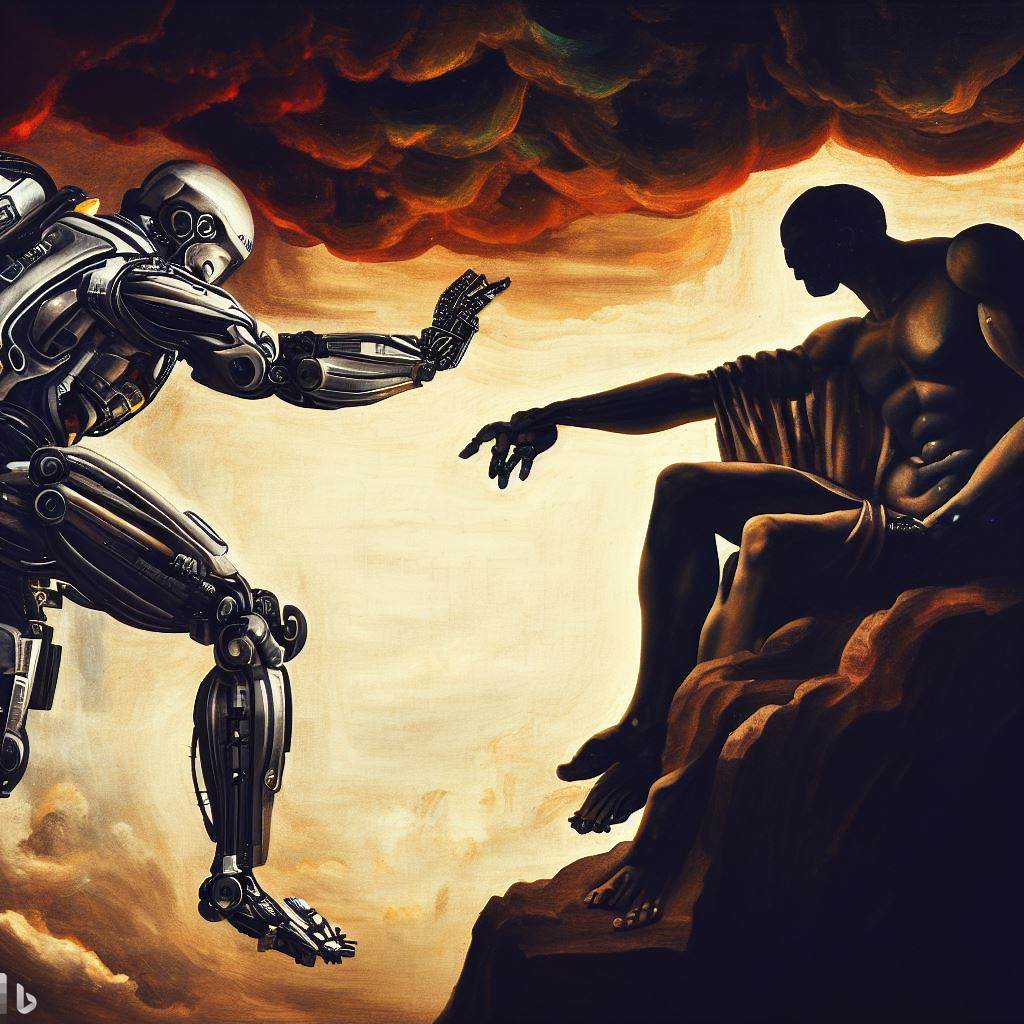

Artificial intelligence (AI) has developed to the point it can generate highly sophisticated, detailed, and relatively accurate images based on textual prompts.

Numerous programs have spawned in recent years, such as NightCafe, WOMBO's Dream, and Stability AI's Stable Diffusion. German artist Boris Eldagsen, winner of Sony World Photography Awards (2023) in London, admitted to being a "cheeky monkey" having generated his victorious submission on OpenAI's DALL-E 2.

The process which unites all these creative programs is known as Machine Learning (ML). In simple terms: a system which allows machines to become 'smarter' by enabling them to learn, predict and adapt from past experience.

In simple(r) terms: machines learn from experience, not human interference.

In this case, AI-generated art utilises a dataset to make predictions about the image desired by the user. It does this by establishing similarities between the words in the prompt and words in its dataset, from which point it attempts to construct an 'accurate' image.

Through constant feedback, AI becomes a better problem-solver, and by extension, a better artist.

The underlying point is that AI-generated art is made using pre-existing human-made art.

Consequently, what is to many people an astounding technological breakthrough, is considered an act of daylight robbery to a growing number of traditional artists.

Although, not every artist is suspicious of AI. In fact, many have embraced the new technology, using it to create, and incorporating it into, their artistic works, works that have since reached the forefront of contemporary art.

The Sincerest Form of Flattery

As of June 1st, the London Design Biennale is well underway. Hosted at Somerset House, this year’s exhibition is dedicated to fostering international co-operation between artists, bringing them together in London to exchange ideas and display their creations.

More than 40 artists are scheduled to present. One of them isn't human.

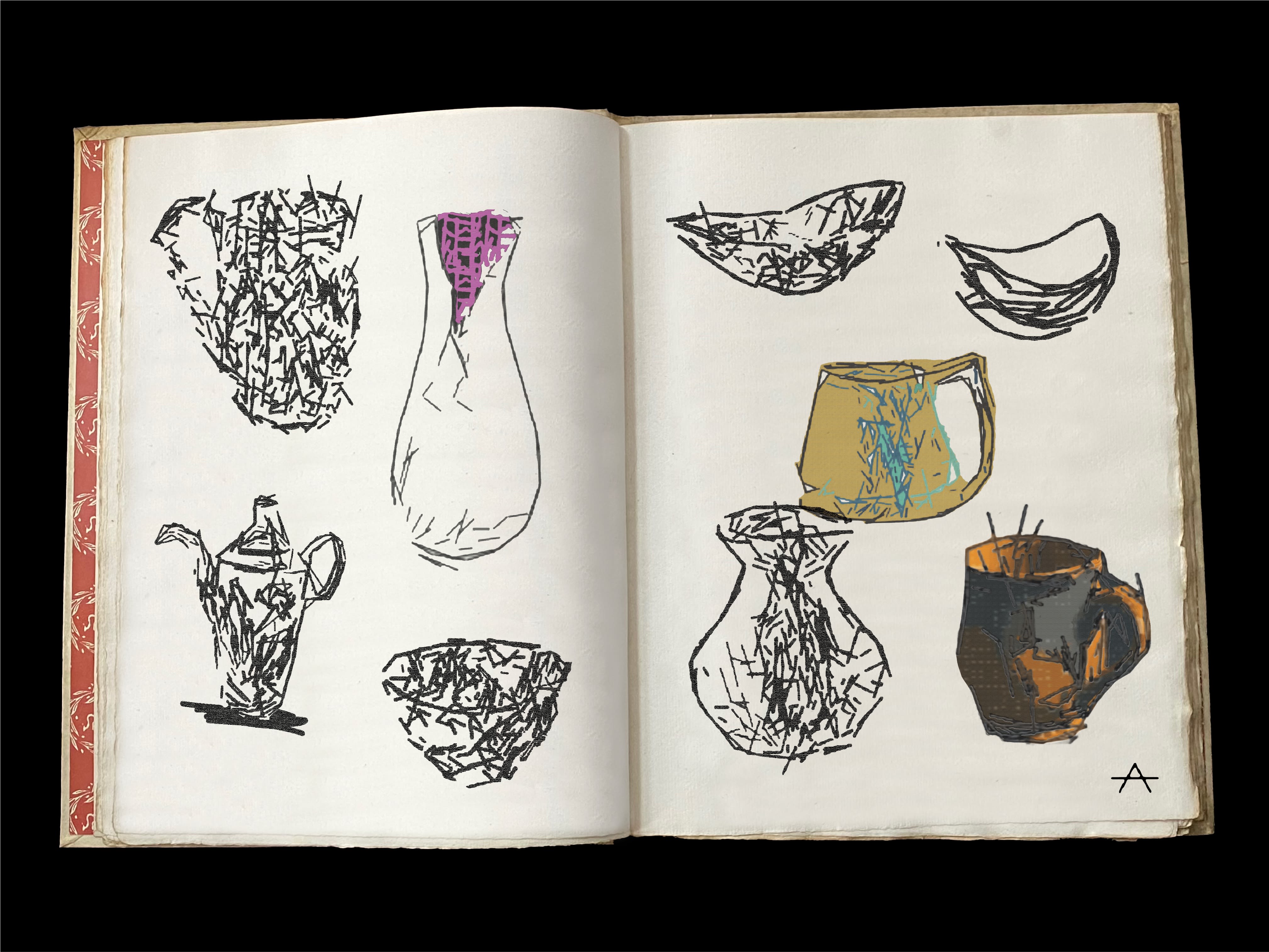

Ai-Da, named after famed programmer Ada Lovelace, is the world’s first ultra-realistic robot artist and the first humanoid robot to feature at the Biennale.

Titled ‘AI Mind Home’, Ai-Da’s display includes a variety of designs and prototypes of household items: bowls, cups, jugs, and plates, a cutlery set, a teapot, and a vase – all designed with AI, all created using a 3D printer.

Ai-Da’s work is derived from a variety of influences: Bauhaus, Picasso, Bloomsbury’s Omega Workshop, the St. Ives Group, and Cornwall’s Leach Pottery.

An array of symbolically utilitarian items, all carefully rendered useless – a statement on the ambiguity of the usefulness of AI in everyday life, one which is being rapidly assimilated to the digital world, entangling human agency with technological capabilities.

Devised in Oxford, built in Cornwall, and programmed internationally, Ai-Da is the brainchild of Aidan Meller, a specialist in modern and contemporary art with over 20 years’ experience.

Meller says: “As advances in AI development accelerate at a concerning pace, Ai-Da’s designs encourage us to think about what impacts we want AI to have in our daily lives.

“The greatest artists in history grappled with their period of time, and both celebrated and questioned society’s shifts. Ai-Da Robot as technology, is the perfect artist today to discuss the current developments with technology and its unfolding legacy.”

To Meller, Ai-Da is more than a robot. Her very persona, as an artist, is a piece of conceptual art, a disruption to the prevailing idea that human agency occupies the epicentre of artistic creation.

Ai-Da concurs: “It is imperative that as a society we consider the implications of increasingly powerful new technologies. I hope my designs stimulate this discussion in the viewer.”

Meller is adamant that Ai-Da is creative, citing the criteria set out by Professor Margaret Boden, Research Professor of Cognitive Science in the Department of Informatics at the University of Sussex: to be creative, works to be new, surprising and of cultural value to be considered creative.

Indeed, Ai-Da’s works are creative. More than creative, they’re quite idiosyncratic. Sure, this is useful when it comes to evading accusations of copyright, although I doubt any of the aforementioned artists are in a caring mood.

Point being, I doubt many people could lay eyes on Ai-Da’s creations and infer that the designs were concocted from famous pre-existing artwork, never mind artificial intelligence.

However, as surprising as Ai-Da’s works are, Meller needs to take some credit here.

After all, for all its impressive capabilities, AI isn’t conscious, it doesn’t possess subjective experience, even if it can make accurate inferences about those that do possess it.

Implicitly, Ai-Da’s work is inseparably Meller’s art as well. The decision to take inspiration from Bauhaus, et al. didn’t fall from the sky.

That said, the challenge of Ai-Da isn't rooted in mechanistic triumphalism, far from it.

In the About section of Ai-Da's official website, it states: "All technological advances bring the good, the bad and the unexpected."

As has been shown, AI-generated art can produce fascinating works (good). As will be shown, it can be perceived as a tool for daylight robbery (bad).

But for now, let me alleviate you of the burdens of the unexpected and shed some light on what we do know...

Who Cares?

A bit blunt? Not at all!

Whilst it's evident that many creators see artificial intelligence as a hamper of artistic potential, many traditional artists are not so convinced, viewing the new technology as one giant plagiarism machine.

Tim Flach, a London-based British photographer specialising in studio photography of animals, is one of an increasing number of artists to view AI as a potential threat to human artistic endeavour.

"AI develops day by day, week by week. The content of this interview may well be out of date by the time you publish it!" Flach informs me.

Far from an exaggeration, the sophistication of machine learning has doubled every three months since 2012, outpacing Moore's Law, according to researchers from Stanford.

"They can call it what they like: 're-appropriation', 'borrowing', supposedly for a higher purpose, whatever, it's still taking the artwork of others," Flach says.

"By scraping images, especially those of a similar style, being made by the same artist, artificial intelligence is taking the art of others and repurposing it to be commoditised."

Given the abundance of pictures Flach has produced over his career, AI has a lot to work with.

This, combined with his distinctive style, Flach's art is ripe for replication by machine learning.

One might say (that is, a lot of people have said - allegedly!) stealing is what art is all about - taking a pre-existing idea or style, and using it for a different purpose.

Although he understands, Flach contends that the production, as well as the product, has indispensable value.

"To value human authenticity is part of our nature - we want to know that things have been created with time and effort, with care," Flach replies.

He's got a point. A film-maker may never lay a finger on a camera's play button, but insofar that the vision captured within the lens is the film-maker's own, one authentically formulated in their mind, it belongs to the film-maker.

Flach stresses the significance of the recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling against The Andy Warhol Foundation, a decision which found Warhol's estate guilty of copyright infringement after incorporating a photograph of musician Prince, taken by Lynn Goldsmith of Newsweek, into an illustration.

The Supreme Court ruled the use of Goldsmith's photograph was "insufficiently transformative" - the photograph had not changed enough to be considered an authentic adaptation or reconceptualization, meaning it did not fall within the remit of Fair Use.

As such, it's no surprise the artistic opposition to AI-generated art is a two-pronged attack: on one hand, AI artists are perceived to be sidestepping (or attempting to side-step) existing copyright law; and on the other, a concern about the place of human authenticity in a world which is being rapidly automated.

In summary, artists don't oppose AI-generated art because it takes pre-existing art and creatively adapts it.

Rather, they oppose AI-generated art because all it does is take; it takes to the extent that artistic transformation is either non-existent or practically trivial.

You might consider yourself a savant; unbewitched by the fakery of modern technology, you (unlike the philistine masses!) could tell the difference between art made by humans and art by made AI.

We can always put that to the test. Take the 'Tyger, Tyger' quiz to see if you can tell the difference:

Conclusion

If this conclusion sounds inconclusive, that's because it is. Both perspectives on AI art, and its consequences for London's art scene, are frustratingly open-ended.

Mind you, that's not the fault of artists, critics, or academics. We can only ask so much, and to expect the unexpected might overly demanding.

However, as all have maintained, this ambiguity is created by the unambiguity of AI's constantly changing nature.

All would agree that AI is a brilliant problem-solver, but that's just it: for many, AI is just a problem-solver, not an artist.

AI lacks creative intent because it has no understanding of art, besides a formation of letters which just so happens to spell "art".

AI can recognise patterns, it can produce patterns, but it cannot give meaning to them - something which humans can do - whether as an artist, critic, or an everyday viewers of art.

Indeed, this seems to be the view of a recent paper from the Oxford Internet Institute (Polin, et al.):

"When conceptualising human and machine creativity, we find that artists highlighted a difference in scope: while ML models could help produce surprising variations of existing images, the artist is irreplaceable in giving these images artistic context and intention."

A source of reassurance for traditional artists? Possibly. Although, real art or not, and to whatever extent, the works of Ai-Da are remarkable in their own right, semantics aside.

Again, whether that's because of or in spite of the process behind them is up for debate.

Whatever general conclusions one arrives at, it is apparent that – if not our endorsement or our disavowal – AI-generated art deserves our attention.

It deserves to be treated not as a distant fantasy nor an ambiguous future, but the present reality of London’s art scene.

All AI art included throughout this article was made with Bing Image Creator. Other pictures are accredited to Ai-Da, Tim Flach, and Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).