The Atonement of a Scandal

Has enough been done to compensate victims of the Windrush Scandal and their descendants?

The arrival of Empire Windrush

Between 1948 and 1973, around 550,000 people migrated to the UK from the Caribbean - many of them ex-servicemen - with the aim of helping the government rebuild Postwar Britain.

One of the first boats bringing a large group of Caribbean migrants was the HMT Empire Windrush, which docked in Tilbury in Essex on 21 June 1948.

Named after the ship, the name Generation Windrush was adopted to describe those who came to the UK as part of this mass migration from the West Indies.

Among them was Jamaican-born Paulette Wilson, who in 1968 was sent to the UK as a 10 year old to live with her Grandparents, in the hope she would have a better life in England.

But in 2015, Paulette received a letter from the British government, classifying her as an illegal immigrant - telling her that she faced deportation despite the fact that she had been living in the UK since she was a child.

Paulette came to Britain legally under the British Nationality Act of 1948, which gave rights to citizens of Britain and its colonies to live in the UK.

Around three years later, under the 1971 Immigration Act, Paulette - along with all Commonwealth citizens living in the UK - was given indefinite leave to remain in the country.

But the Home Office failed to keep a record of this - or issue her any paperwork confirming her status.

Like so many others who came to the UK from the Caribbean as children, Paulette considered herself to be British. But, like so many others, by no fault of her own, she lacked the documents to prove this.

Decades of deep-rooted racism

Despite encouraging migrants from Commonwealth countries to settle in the UK between the late 1940s and 1973, a Government report recently leaked to the Guardian concluded that every piece of immigration or citizenship legislation introduced between 1950 -1981 was designed - at least partly - to reduce the UK's non-white population, planting the seeds of deep-rooted racism underpinning what would become known as The Windrush Scandal.

A hostile environment

Despite not issuing documentation at the time, in 2010, during an office move, the Home Office destroyed thousands of landing card slips recording the arrival dates of Windrush immigrants in the UK - records which for many were the only proof they were in the UK legally.

On 25 May 2012, in an interview with the Daily Telegraph, then Home Secretary Theresa May declared that her aim as Home Secretary was to create a "really hostile environment for illegal migration” here in Britain - marking the start of what is now known as the Hostile Environment Policy.

The Home Office subsequently changed its rules, requiring citizens to prove their resident status before accessing services like the NHS.

Uncovering a scandal

The Windrush Scandal began to emerge in 2017, after it was revealed that hundreds of Commonwealth citizens - many of whom were from the Windrush generation - had been wrongly caught up in the hostile environment immigration policy brought in under Theresa May, with many suffering catastrophic consequences caused by the Home Office’s failings.

Many endured wrongful arrest, forced detention and separation from their families - with others experiencing loss of employment, access to welfare benefits and NHS services, housing and livelihoods.

At least 164 people were mistakenly detained or removed from the UK.

An apology

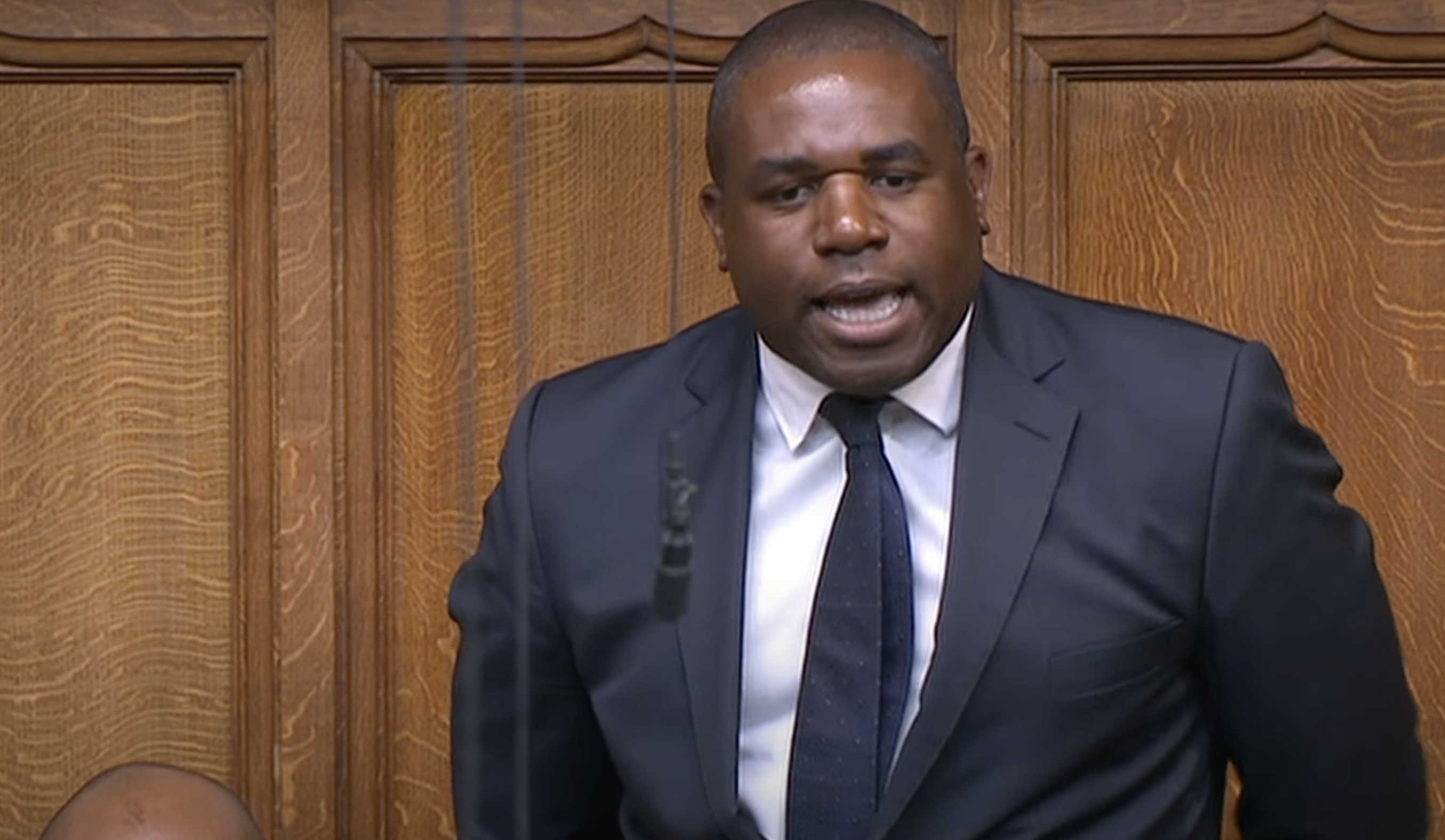

On 17 April 2018, following a passionate speech by David Lammy MP in the House of Commons the day before, aimed at Home Secretary Amber Rudd, Prime Minister Theresa May apologised to Caribbean leaders for the controversy during a Downing Street meeting.

A resignation

Around two weeks later, Amber Rudd was forced to resign, admitting that she had "inadvertently misled" the home affairs select committee over her knowledge of deportation targets relating to the removal of illegal migrants.

Compensation

In a bid to address the array of problems caused, the Home Office launched a compensation scheme in April 2019, which they claim aims to "put right the terrible injustices faced by some people from the Windrush generation" by financially compensating those who suffered loss in connection with being unable to demonstrate their lawful status in the UK.

As of April 2022, a total of £48.7m has been paid by the Home Office to victims of the Scandal.

When approached for comment, a Home Office spokesperson said: “The mistreatment of the Windrush generation by successive governments was completely unacceptable and the Home Secretary will right those wrongs.

“We continue to process claims under the Windrush Compensation scheme which has now paid out more than £40 million across 1,037 claims, with a further £8.2 million offered.”

Criticism

However, the Windrush Compensation Scheme has received criticism by victims, their families and campaign groups - who say the process has taken too long and applications are too complicated, with the forms described as "horrendous to fill in". Others say that the compensation offered is "insulting", and some victims have had to reject offers which fall far short of covering the money they lost.

Campaigner Charlotte Tobierre, whose father Thomas is a Windrush victim, even described the scheme as "traumatic".

Speaking at a Windrush event at the University of Westminster on 20 June, Charlotte said: “The scheme is still very difficult for people. It’s stressful and it’s hard and it’s traumatic. Now I’ve taken over that on my father’s behalf - I’ve taken on the fight for him."

In fact, a report by the Home Affairs Committee released last year concluded that instead of providing a remedy, the scheme has in fact "compounded the injustices" experienced.

As of September 2021, around 20% of the estimated 15,000 eligible claimants had applied - with just 5% receiving compensation. At least 23 people passed away before receiving a penny.

Long-lasting scars

Many of those who experienced traumatic actions at the hands of the Home Office have been found to continue having negative experiences as a result of hostile immigration policies.

This has been consistently associated with poorer mental health, with irreversible damage and loss experienced not just by the individuals affected but also by their families and communities.

Social commentator and historian Professor Patrick Vernon OBE is now calling for affected families to be given a "mental health MOT" to check physical and mental health, alongside compensation.

Professor Vernon, along with many others, including Charlotte, also believes the scheme should be taken away from the Home Office and into the hands of an independent body.

Reparations

Discussing the approach of the Home Office's scheme, Associate Professor of Global Health the UCL Institute for Global Health Dr Rochelle Burgess, whose work focuses on mental wellbeing among communities said: "It’s about financial compensation alongside structural investment in communities.

"You need to think about how the wider community has been affected by this - or potentially they are being lined up to be affected by this in the future - and the sort of policy responses that you can put in place can certainly compensate for that.

"All trauma is compensable. It all can be if you have a very wide remit on what counts as recompense for various forms of violence. And people should always have the ability to determine what they would like the compensation to be."

The Ties That Bind

Together, Professor Vernon and Dr Burgess have now launched a new project, The Ties That Bind, which explores the intergenerational mental health consequences the Windrush Scandal has had on Caribbean and Black African families in the UK.

The project is the first study of its kind to map the mental and physical impacts of the scandal and the UK's hostile immigration policies, not only on those who have been directly affected, but also their family members - who all may have experienced mental health issues such as depression, anxiety and race-related trauma.

Taking place over six months this year, the project aims to map perspectives and realities of living through the Windrush Scandal within families and their wider communities.

Discussing the research, Dr Burgess said: "The project exists in two parts. The first part is a demographic and mental health survey with survivors and their family members and kin networks, where we're asking them to reflect on any sort of questions related to their experience with the scandal and their mental health status.

“That’s a larger sample of people we’ll be asking to participate - around 100 or so. Selected from that, we’ll be inviting a maximum of 50 people across two sites.

“We’ll be undertaking workshops for an arts-based action oriented project, using a methodology called “Photovoice”, which invites people to reflect on particular issues in their lives through photography.

“This is something that can be helpful if people are dealing with issues that are particularly difficult or traumatic, and creates a pathway for them to share stories in ways that they control rather than it being mediated through a researcher's perspective on what questions to ask.”

The results of the Photovoice project will be publicly shared and exhibited online in collaboration with the UCL Health of the Public Creative Health Community.

A policy roundtable will also be held later this year to engage survivors, leading activists, mental health practitioners, academics and policy makers to raise awareness and encourage support and change.

"We want to bring people together to reflect on the findings and have discussions about what the best ways forward are, in terms of what we find," Dr Burgess added. "We want to open up a conversation that makes people think about having specific mental health support for the community that have been broken as a part of justice."

Communities

The Ties That Bind will focus the experiences of those from two sites in England, one of which will be in London.

Many communities throughout the city have been affected by the scandal, including Brixton in the London Borough of Lambeth.

Of the more than one thousand passengers on the Empire Windrush - around 500 of them from Jamaica - more than 300 would find their way to Lambeth, with many settling in Brixton.

The legacy of Windrush is still felt in the area - and to mark the 50th anniversary of the arrival of the first ship, the public space outside the Black Cultural Archives was renamed "Windrush Square".

Wolverhampton

The project will also focus on communities in Wolverhampton - the home of Paulette Wilson.

Likkle but Tallawah

After receiving her letter from the government, Paulette's daughter Natalie booked an appointment with the Home Office - when she was told that her mother had six months to leave the country.

Paulette was later arrested on two occasions, spending a week wrongfully detained at Yarl's Wood immigration removal centre - before being transferred to another centre in Heathrow in 2017, ahead of a flight to Kingston.

Only a last-minute intervention by her MP, Emma Reynolds, and charity the Refugee and Migrant Centre in Wolverhampton prevented her from being deported.

After receiving confirmation that she could remain in the UK, Paulette and her daughter spent several years campaigning and raising awareness of the experiences of thousands of those from the Windrush Generation who were accused of being in the UK illegally.

She inspired hundreds - if not thousands - of people to come forward and share their stories, leading to the scandal eventually being exposed.

On July 23 2020, Paulette died unexpectedly in her sleep at her home, aged 64. She is believed to be one of several victims of the Windrush Scandal who died from a broken heart.

Just weeks before her death, she had delivered a petition to Downing Street signed by 130,000 people calling on the Government to speed up compensation payments. Paulette passed away before she was able to send off her application.

Credits

Images

• Image one: Caption: HMT Empire Windrush. Source: Imperial War Museum / Royal Navy photographer official / Wikimedia . © IWM FL 9448

• Image two: Aerial views of the Troopship Empire Windrush burning off Algiers. March 1954. Source: Wikimedia. © IWM A 32891

• Image three: Windrush passenger looking into Howard's camera on the platform at Waterloo. Source: Howard Grey / Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0).

• Image four: Theresa May apologises. Credit: still from a video by The Independent.

• Image five: David Lammy Windrush Scandal speech. Credit: still from a video by ITV news.

• Video one: David Lammy Windrush Scandal speech. Contains Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence v3.0.

• Image six: Amber Rudd resigns. Credit: still from a video by BBC / BBC Politics Live.

• Image seven: Dr Rochelle Burgess. Credit: Dr Rochelle Burgess / UCL

• Video two: Windrush Legacy in Brixton. Credit: Evie Calder

Music

• Old Harbour Ambiance by klankbeeld / freesound.org (CC by 4.0)

• Ship Horn by monotraum / freesound.org (CC 1.0)

• Pirate Ship at Bay by CGEffex / freesound.org (CC by 4.0)

• Crossroads Bus Stop by djafifa / freesound.org (CC by 1.0)

• Documentary by Music Unlimited / Pixabay (Pixabay License)

• April Showers (Moody Ambient Cello) by Dream-Protocol / Pixabay (Pixabay License)

• DesiTalk Exclusive - Life is Strange by madIRFAN / Pixabay (Pixabay License)

• Brixton Market lunchtime by freesound.org (CC by-NC 3.0)