The Brain Drain

How Northern Ireland continues to fight high-skill emigration 25 years after the Troubles

Sam Lindsay applied for a job in London as an engineer. By that point, he had not lived permanently in Northern Ireland, his native land, for four years. For him, and many others, the choice to stay put felt an obvious one.

"When I come back to Northern Ireland I feel a reduction in culture, in diversity, and the homogeny of home", said Lindsay.

"I think Northern Ireland causes you to step into line, whereas when you move you can step out of that line, and explore what you like without a kind of social judgement."

Now living in Battersea, he is part of a growing cohort that have contributed to an endemic issue for Northern Ireland, known as the Brain Drain.

The Brain Drain

The Brain Drain refers to the consistent flight of knowledge from a country, as school leavers move away for university and stay to work in the country of their further education.

It is a trait often associated with low-income nations. Northern Ireland, with a Gross Value Added (GVA) per person in line with rich countries, is an outlier.

The reasons are myriad, straddling economic and social, past and present.

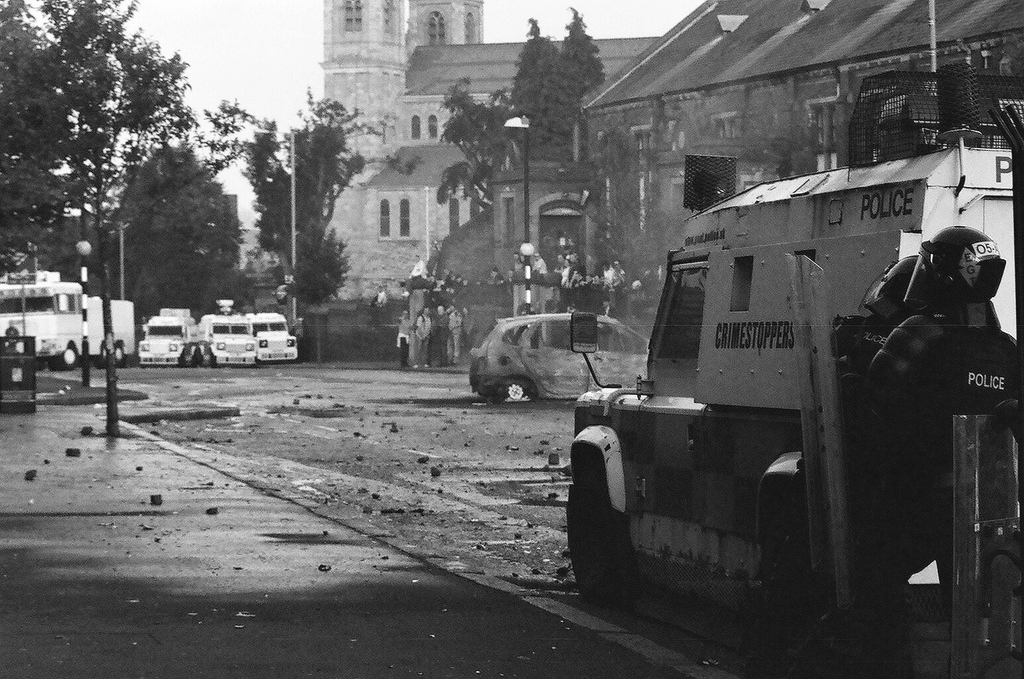

The shadow of the past

For 30 years, Northern Ireland was engulfed in sustained civil conflict, known as The Troubles. Between 1968 and 1998, more than 3,000 people were killed as a result of the Sectarian conflict between Unionists and Nationalists.

Perhaps more impactful on the society was the exodus of residents from the country. Between 1968 and 1998, a cumulative 184,000 people left NI behind.

Nearly 45,000 left when the violence was at its worst between 1971 and 1973. Those that stayed and survived the conflict carry their own scars.

And the fog of the future

It means that despite NI’s young people having little recollection of a time before the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, those scars run deep.

Deprivation can be high. While the cost of living is lower in the region than overseas, income has also typically lagged the rest of the UK. The rate of death by suicide for men is 19.4 per 100,000 people, compared to 12.9 in the Republic of Ireland and 15.3 in England.

This is in part a result of intergenerational trauma, as pervasive issues around masculinity and mental health mix with post-traumatic stress disorder to leave a vacuum of support.

NI also grapples with social obstacles, with the devolved NI Executive typically a follower rather than a leader on liberal causes.

Abortion legislation was pushed through by the UK Government while the Executive was shut down. It took Northern Ireland six year to legalise same-sex marriage after it was legalised in England and Wales.

And most policy continues to be drawn across old battle lines inherently linked to the country's divided past.

For many of those able to attend university overseas, it continues to feel like a permanent escape, rather than a brief adventure.

"Young people at the start of their careers tend to move to London and exit when they get to about 40 or 50, and then they tend to come home," said Dr Ian Shuttleworth, a senior lecturer at Queen's University Belfast.

"And migration is highly socially selective. So the more educated you are, and the younger you are in adulthood, the greater chance you have of moving."

But in Northern Ireland, Shuttleworth accepts other social factors, like the presence of the socially conservative Democratic Unionist Party, may provide an added incentive for young people to leave.

Ian Shuttleworth explains why the Brain Drain happens, and suggests social reasons for why it could be more acute in NI.

Society and culture played a role in Lauren Patchett's move to London, where she is studying a master's in Fashion at Central Saint Martins.

Patchett, 23, feels more at home in a city where she sees more diversity of opinion and experience.

She said: "In London people don’t really have time to care about what you look or dress like, so for the most part, you are able to present exactly who you want to be.

"I definitely feel more at ease in sharing social opinions in London.

"You can learn from the different collective people surrounding you, and have interesting conversations and debates that will ultimately make you a more thoughtful and aware person."

Why do they go?

But for most, the move is more a matter of economic convenience.

Sam Lindsay, 27, joined an increasing number of Northern Irish people taking their right of passage in leaving the country for higher education in Great Britain. It is a passage that often turns into a permanent settlement.

The equivalent of 1.8% of 18 – 24 year olds left NI for the rest of the UK in 2019/20, compared with 0.7% in 2001/02.

He said : “I was looking for jobs in Northern Ireland but they were just difficult to find.

"I saw things like graduate programmes in big English companies as a great opportunity, one where I could get the training I wanted and get paid well.

"That was a lot harder to find in Northern Ireland."

Lindsay felt that even if he did find employment in Northern Ireland, the opportunity for progression would have paled in comparison to what he gained in London.

Pivotal, a public policy think tank in Northern Ireland, offered a sobering reality of the number of people making the same decision as Lindsay and Patchett.

Nearly two thirds of students who leave NI for University end up taking jobs in other countries. For every GB student that travels to NI to study, more than five go the other way.

The impacts, according to Richard Johnston, Associate Director at the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre, are severe.

Johnston said: “Economically, you are losing your brightest and best.

"It means we're falling back on competitively with other regions, because in effect we don't have the best people making the best products.

"It also means that companies think twice about starting operations in NI, without a suitable access to talent."

Pivotal suggested that the lack of higher education places in Northern Ireland should be expanded to keep up with the supply of students.

For every 100 applicants to a Northern Ireland university, there are 60 places, compared to 120 in England and 130 in Wales.

Pivotal argue that if younger people stay for higher education, they are less likely to leave after.

But in trying to keep young people from leaving, Johnston fears other shortcomings are being missed.

Johnston feels the country should focus on driving down economic inactivity – which in NI is by far the highest across the UK regions – and improving the number of young people gaining higher level qualifications.

Until then, Johnston fears, NI will continue to appeal to fewer young people.

"Ultimately it's a drag on productivity, competitiveness, leadership and innovations.

"It's an economic drain."

A debt repaid

In the most clinical sense, the rest of the UK might consider NI to be a drain of its own. The region takes in just over £20 billion of tax revenue per year to fund its public services. That falls well short of the total expenditure in NI, which amounts to £30 billion per year.

That shortfall is subsidised by the UK government – in particular London – to the tune of more the £5,000 per person each year through the Barnett formula. London meanwhile, runs an annual surplus of £4,000 per person.

In return, it is put that NI, and other peripheral UK regions, supply the London economy in two ways: with food from vast agricultural land, and in the form of talented young graduates who choose to innovate the GB economy, rather than the NI one.

Johnston argues that NI may be fulfilling a requirement of facilitating talent in return for that sizeable funding.

Johnston said: “It may be part of the deal that we provide labour for certain sectors, a good place to raise children and a reasonable quality of life.

"But is it better for some of those kids to then go to London where they will earn the highest wage?"

It is a tenuous relationship reliant on trust and a general feeling of economic and political stability, a relationship that was – perhaps irreparably – damaged in 2016.

Brexit

The vote to leave the European Union was one more dependent on the sentiment of English and Welsh voters, rather than Scotland and NI, where the link to the UK has always been more resistant.

NI voted to remain in the EU by 55.8% to 44.2% leave.

Shuttleworth noted that the EU's expansion helped contribute to shifting migration patterns in Northern Ireland over the last two decades.

"We went about 20 years ago to net migration balanced, and in some years we had a net inflow", Shuttleworth said.

"The big event has been the growth of communities inside Northern Ireland, like the Portuguese in Dungannon, Cookstown and Craigavon."

But NI is now struggling to plug the flight of its younger demographic with the inflow of EU migrants.

Last year was only the fifth year in the last 20 that NI saw a net exodus of people. 3,200 more people left the country than entered in 2019/20.

In the long run, Johnston worries that a continued exodus of young people will soon begin to bite if immigration is unable to fill the gap.

But in the short-run, it has also meant sharp wage inflation. Wages in NI increased by 7% in 2021, having risen by a total of 2% in the nine years between 2011 and 2020.

Others are optimistic that NI can begin to benefit from an agreement that keeps them in the EU customs union.

At a meeting of the Northern Ireland Affairs Committee, Gareth Hagan, deputy chief executive of OCO Global, said both foreign companies and GB-based companies now plan to set up operations in NI.

Hagan said: "“I do know, I have it on good authority, that the investment pipeline in terms of investors with an interest in Northern Ireland is stronger than it’s ever been.”

And out of uncertainty, can breed further opportunity.

Renewed hope

That hope of opportunity is no more evident than in NI's thriving tech sector.

First Derivatives, Kainos and StatSports are just a few multi-million pound, NI-based global companies hiring in the high-skill, high-wage technology sector, while foreign direct investment (FDI) continues to grow.

Angelo Marica, 27, was recently hired by Microsoft, who have set up an academy in Northern Ireland. It is a reality he could scarcely foresee a matter of years ago.

Angelo originally left NI as much for job opportunities as for a different culture, one detached from his NI upbringing.

Having studied in Liverpool, Angelo had planned to move to Brighton and work for British Telecoms (BT), rarely looking back to NI for his ideal career.

Angelo said: "This is a really small pool in Northern Ireland, and there were really few technical jobs.

"But now data is exploding, the salaries are increasing, and the competition for talent is happening among employers rather than jobseekers."

The change in employment fortunes is beginning to help change Angelo's relationship with home.

"The hope of something getting better is enough to keep you wanting to stay there."

Listen to Angelo talk about his hopes for the future of NI