The division of domestic labour

Why are mums doing most of the chores and childcare during lockdown?

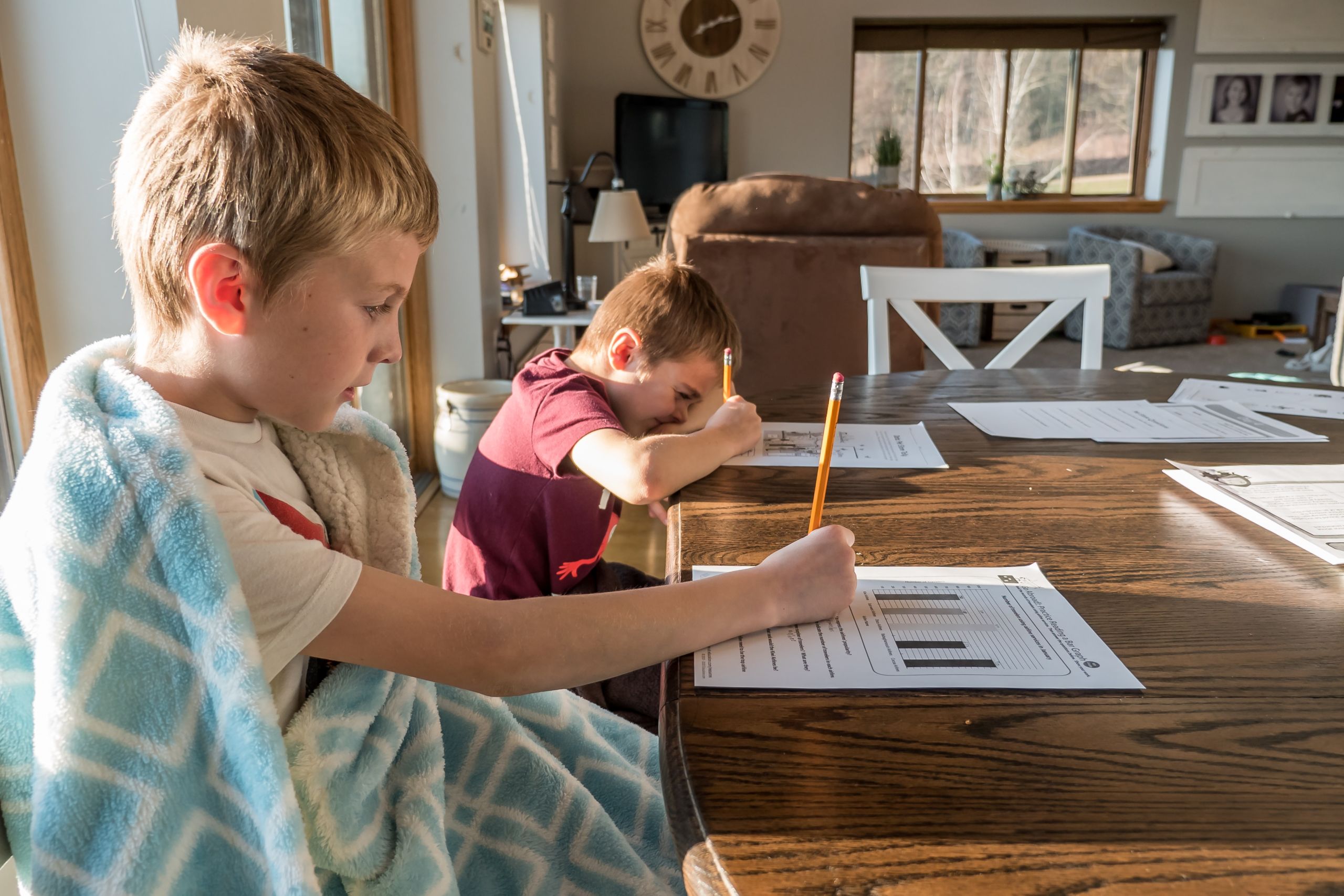

As countries locked down and schools closed in response to Covid-19, parents were forced to undertake six months of domestic labour and childcare.

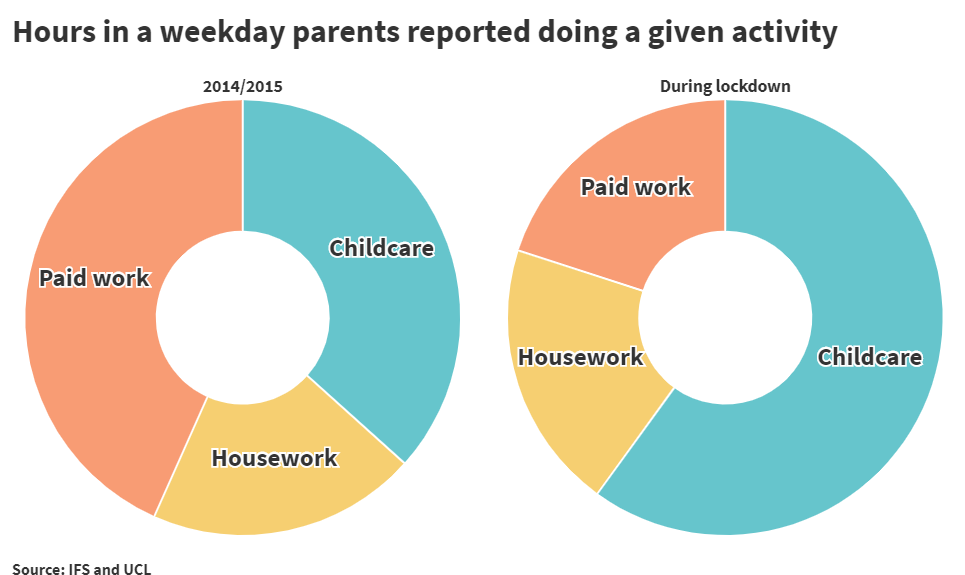

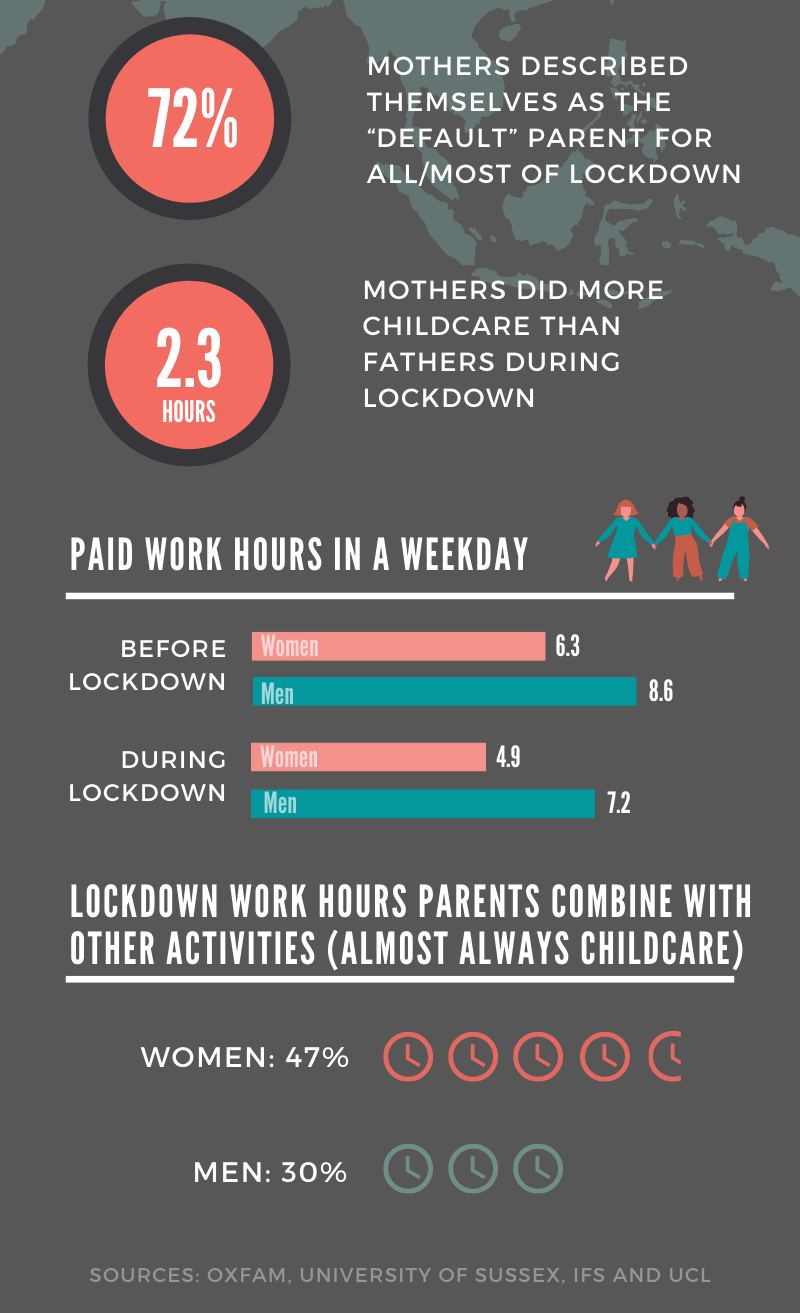

Research has shown women are generally doing more of this domestic labour during lockdown, regardless of whether they are balancing it with paid employment.

The vast majority of families have defaulted into centuries old patterns whereby the home is the province of women.

Yet women were already doing the majority of this work in the home, meaning the effects of lockdown have only exacerbated existing gender inequalities.

Caroline Whaley is the co-founder of Shine, a consultancy firm for women in business, and said:

“One silent victim of the pandemic remains the same: women’s independence.”

“Based on the conversations we’ve had, compared to their male partners, women do more housework, carry more of the emotional labour and have less me-time.”

A typical lockdown day for a Shine client:

6 AM Wake up and start answering emails

9 AM Start home schooling the kids

12 PM Feed kids and return to work

6 PM Make dinner and then do house chores until 10 PM

Meanwhile, her partner works in his study all day, only emerging for meals.

Ms Whaley said: “It highlights an alarming trend. Our family systems are regressing and this is being subconsciously supported by the government removing its expectations of companies to report their gender pay gap statistics.”

As women are more likely to work on zero hours contracts or part time, and because of the sectors they primarily work in, they have been more likely to have lost work, thereby increasing the already ample income gap.

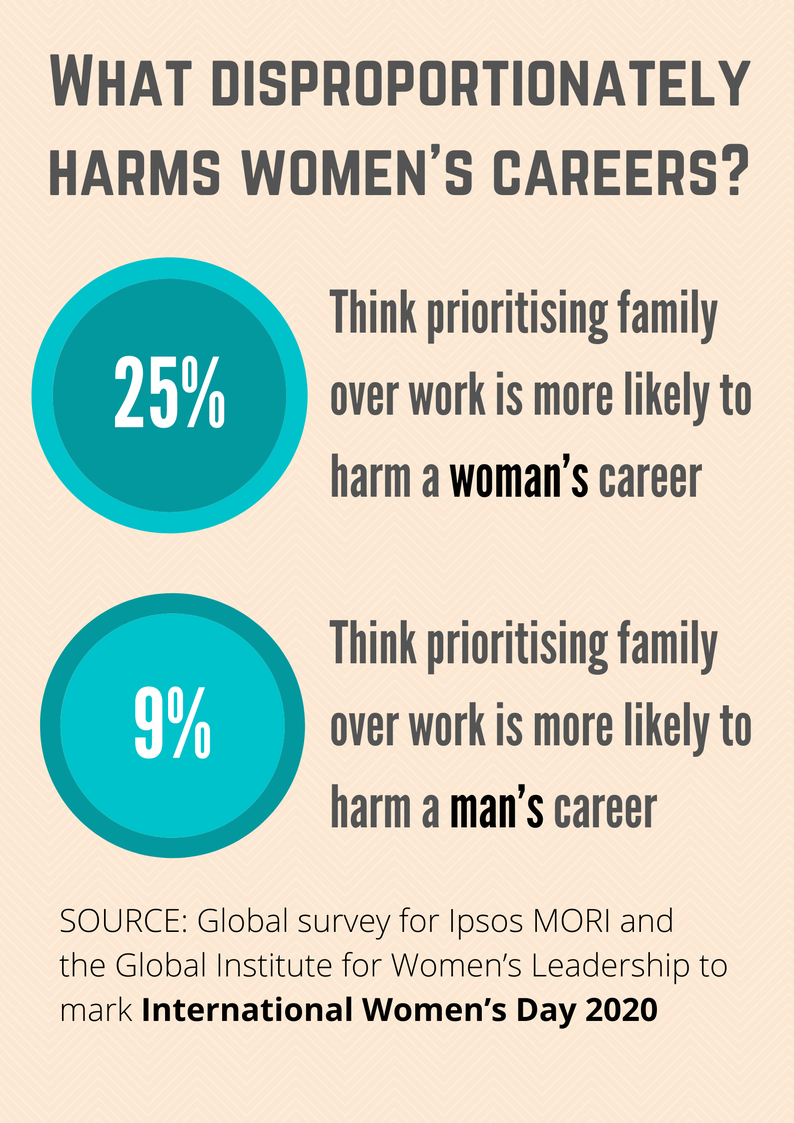

In addition, mothers juggling a full-time job alongside a heightened household burden are being forced to engage in work less, which could have a detrimental effect on their career in the future.

73% of mothers say working from home has been “difficult” or “very difficult” in the University of Sussex research.

Paula Sheridan, a coach whose firm Unwrapping Potential works with professional women, described the range of household situations among her clients who are the sole income-earners.

Paula Sheridan of Unwrapping Potential

Paula Sheridan of Unwrapping Potential

Some have partners who are no longer working and have assumed all the domestic chores. In other instances, they are regularly interrupted by their children as fathers are not keeping a firm eye on them.

Ms Sheridan said: “My worry is that women are getting fewer hours of work in the day and it will reinforce this idea that once women have a family they're distracted and not committed to their career, which is already an assumption in the workplace.”

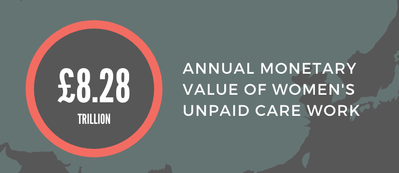

In January, Oxfam International reported women do more than three-quarters of all unpaid care work across the globe, amounting to a staggering 12.5 billion hours a day.

Source: Oxfam International

Source: Oxfam International

This weight of their domestic responsibilities means 42% of women globally are unable to do a paid job, compared to only 6% of men.

Domestic labour’s sheer drudgery and necessity are in proportion.

In 2012, feminist activist and scholar Silvia Federici wrote of how this labour is normalised as 'housework' and obstructed from material or economic acknowledgement.

These foundational inequalities still exist decades after campaigns such as Wages for Housework in 1972, which Ms Federici was part of.

Its founder, Selma James, wrote in the Independent earlier this year:

“It is extraordinary that those who reproduce the human race are still unsupported and impoverished for this fundamental biological and societal work.”

Cultural representations of women as mothers legitimise this position and present domestic labour as a result of inherent maternal love. Girls grow up babysitting and playing with toy babies, gearing them towards a future as a caregiver.

Ms Sheridan said: “There isn't anything wrong with the roles that we ascribe to femininity or a female gender. What I have a problem with is the fact that all those things are seen as shameful for boys.”

Modern conveniences have eased the toil of domestic work, but are far from removing it entirely.

The attitude towards domestic and maternal labour is in part owing to systemic sentiment, but also to the nature of the task itself.

A large portion of the domestic work women bear is the ‘mental load’.

Mental load:

The burden of remembering, and usually performing, the numerous tasks required to keep a household functioning: scheduling pickups, planning meals and remembering to book doctors’ appointments.

This form of labour is invisible, so you only know it hasn’t been done when the household order begins to fray.

Haley Swenson, Deputy Director of the Better Life Lab, said: “We know that it's overwhelmingly women who do this. It’s one thing to redistribute the tangible concrete tasks in the household, and another to redistribute who's going to think about this work.

“One of the pieces of advice that we've been giving, and that marriage therapists give, is to make that work tangible by writing it down. Actually list these things as tasks.”

Ms Sheridan said: “It doesn't happen with just one week. It takes solid commitment to keep it going, because they've never had to do it before, so why would they?”

Reports such as those detailed could potentially be unproductive if they pit men against women, and researchers are keen their findings do not create a battle of the sexes.

While outmoded patterns of domestic labour manifestly persist, three quarters of fathers said mothers and fathers should equally share caregiving work in a report from the Better Life Lab.

Furthermore, one third of fathers said there are obstacles preventing them from being the dads they want to be, citing barriers such as money concerns, the demands of their job and lack of time.

Dan Reed, founder of the support group for working fathers, Career Dad, described the feedback during lockdown: some are relishing the opportunity to spend more time with their children while others are struggling to acclimatise.

Dan Reed of Career Dad

Dan Reed of Career Dad

The gender pay gap means men tend to be bringing home a higher income than women; as a result, their jobs often take priority, while their partners are left to care for the home.

At a Career Dad Virtual Hangout, Mr Reed said fathers reported they are doubling down with work for the foreseeable future to secure their job in the face of looming redundancies.

Mr Reed said: “I'm hearing a lot of guilt; work has ramped up, the family are all at home and the kids don't understand why their dad is in the house but I can't play with them all the time.

“A lot are feeling like they're not really winning with family but also not winning at work and I think that's probably one of the most vicious cycles.”

Dan Carlson, Assistant Professor in the Department of Family and Consumer Studies at the University of Utah, said:

“Men don't want to be just breadwinners, but that's what is expected of them at work, and so they're fearful of lack of promotion or lack of raises. There's a stigma associated with taking leave and pulling back a bit.”

Mr Carlson reported a notable increase in the amount of domestic labour and childcare fathers are doing during lockdown, regardless of whether they have lost their job, been furloughed or are still working.

“That’s interesting because past research has shown that when men are unemployed or out earned by their partners, they assert their masculinity and refuse to do these ‘feminine’ tasks. We're not finding that now.”

Mr Carlson also cited research that shows men who take leave continue to do more housework and childcare once they return to work, suggesting this increase in their household contributions could continue when we return to pre-pandemic work patterns.

Paula Sheridan has a background in the pharmaceutical industry and said: “In pharmaceutical sales you cannot have a hanging comparison, and that is a hanging comparison: men are doing more. More than what? They're doing more than they were, that is absolutely true. But are they doing more than the women in general? No.

“Families where men have taken on more responsibility in the home for a period of time, that does tend to continue. So, one hopes that they think they're going back to normal but it might well be a new normal.”

It is of note that previous crises have had vastly dissimilar effects on gender equality. The First and Second World Wars saw increased freedom for women to participate in the labour market under the collective assertion ‘We Can Do It!’

Although these changes were short-lived, they are a far cry from the conservative behaviour this crisis has imposed on many households.

Immense progress has been made for women’s independence in the last 50 years: legislation around maternity rights and equal pay, childcare and after school clubs.

Yet, the effects of lockdown show a reconsideration of who does the chores and takes care of the children needs to take place.

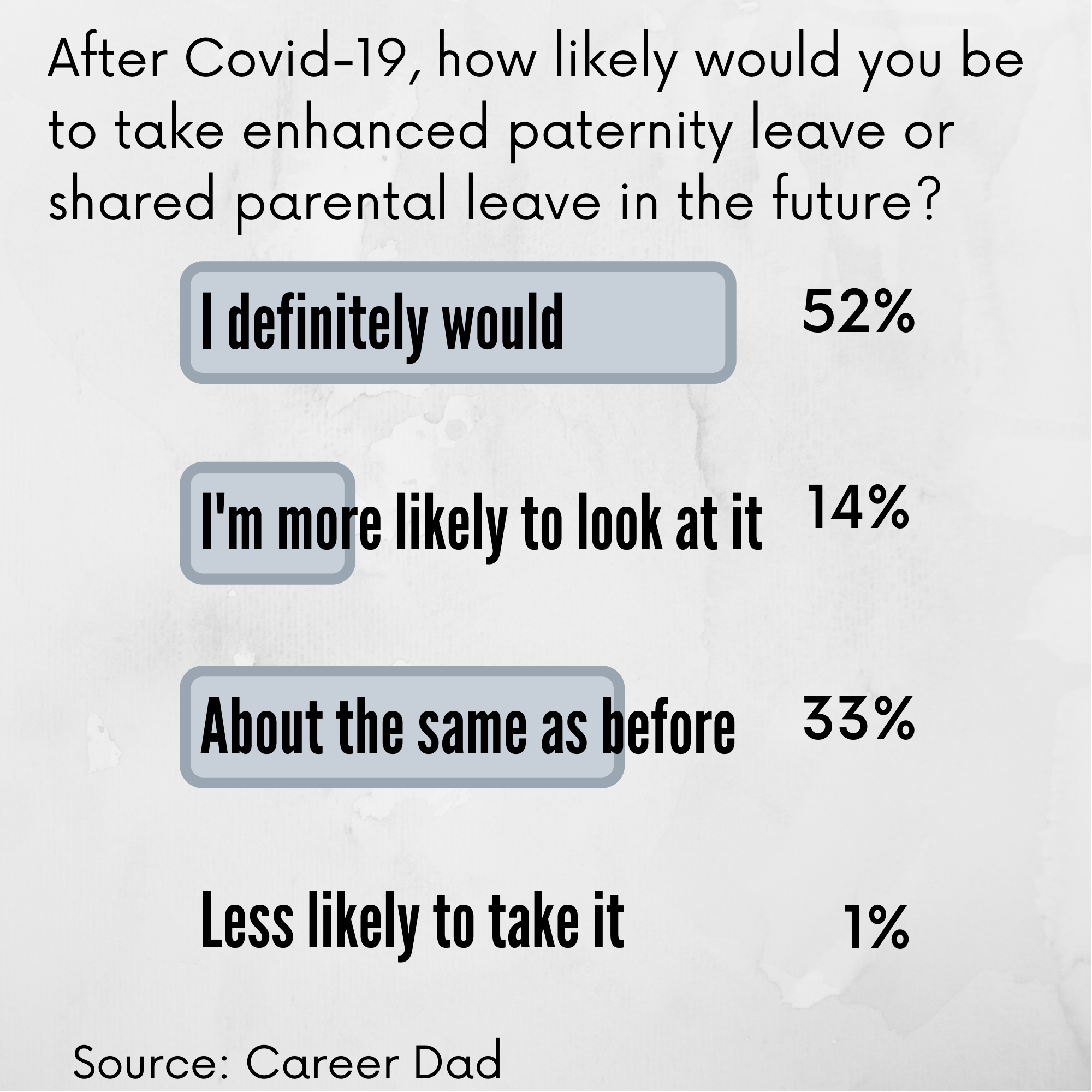

Mothers and fathers alike point to proper paid paternity leave as fertile terrain to enact a shift in the underlying assumption care is women’s work.

One in three of eligible new fathers take paternity leave, according to research from the commercial law firm EMW.

Ms Sheridan said: “Male leaders in organisations should be taking parental leave to model that it is expected. We all have families, and we all need to make our commitments to them.”

Mr Reed said: “One of the main reasons for the lack of paternity leave take up isn't because dad's don't want to do it, it is the perception in the workplace; will they be seen as someone that is ready for that next promotion if they're asking for three months shared parental leave?”

Referencing this Career Dad Survey, Mr Reed said: “If you marry that up with the 2% that actually do take paternity leave in the UK, there's a huge disparity there. So I'm hopeful that this has shown, albeit warts and all, that it is possible to manage a job and be more active in their kids’ lives.”

The first few months of raising a new-born are hard to replicate and can be akin to a baptism of fire for mothers and fathers alike.

Paternity and maternity leave are vital because it is when parents have the opportunity to make mistakes and learn how to care for their child.

Ms Sheridan concludes: “Women are doing more of this domestic work because they're used to doing it, and the reason they're used to it is because they had the opportunity to do it while they were on maternity leave. Most fathers didn't get that opportunity, but now is their opportunity.”

While the immediate effect of lockdown has been to fall back on harmful underlying assumptions that mothers are the default parent and domestic work is women’s work, the lasting legacy of the pandemic need not be so calamitous for gender equality.

New domestic labour patterns have emerged in lockdown, presenting an opportunity for revised approaches in more households. Once the crisis abates, investing in flexible working hours and paid leave could enable men to shoulder their share of the domestic workload.