The Forgotten Frontline

COVID's unpaid hotel quarantine workers

IN February 2021, hotels across the UK transformed into government-designated quarantine accommodation.

UK nationals or residents arriving into England from “red list” countries were required to stay for 10 days in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

These hotels were managed by thousands of security officers, recruited by subcontractors of security giant G4S, which successfully secured a £66 million contract from the Department of Health and Social Care to deliver a ‘managed quarantine’ between February and October 2021.

It was a period of extreme uncertainty with the arrival in March of the Delta variant, a new and highly infectious COVID mutation, which rapidly became the UK’s dominant strain.

The Quarantine Surge

During the summer months, the number of people staying at quarantine hotels in England surged. Security officers were at the frontline and in regular contact with passengers arriving from high-risk countries.

Days were long and working conditions difficult, says Rachid, a British Algerian who worked at Victoria Park Plaza and Holiday Inn Earls Court between March and October 2021. “Many of us often worked double shifts and travelled hours to and from the hotels.”

He adds, “I worked extremely hard for this money, getting up every day at 4am, travelling two hours to work before a 12-hour shift, and usually not getting home until 10pm. My family is back in Algeria, so it was an exhausting, lonely and stressful time.”

The Rumours

In early August, rumours started to circulate across the hotels that workers would not be getting paid for that month.

“I didn’t pay attention to it at first, but suddenly it was true, we hadn’t received our wages”, says Saima. She worked as a security officer via AKD for quarantine hotels, including Radisson Blu, Courtyard by Marriott, and Renaissance hotel.

Security officers continued to work with the promise that payments were simply delayed. However, weeks turned into months and thousands of people are allegedly owed missing wages.

Desperation quickly began to set in among workers, who frantically and repeatedly contacted anyone they could think of for clarification, but responses were vague and soon they stopped altogether.

“We’ve never been given a clear reason from our contractors, G4S or from the Department of Health and Social Care about where the money is,” says Waheed, who worked as a security officer at Radisson Blu’s Heathrow branch.

Ali, who worked as a duty manager at the Radisson Red over the summer months and says he is now owed £11,000, faced a similar wall of silence. “We called and emailed, but no one is listening to us, no one is trying to help us. I don’t know what is the next step, what else can we do."

"How long can we borrow money from our friends and family? How long can we just wait for them?”

He added, “People like me are in similar situations in London, Manchester, and across many other cities. None of us are getting paid and now all we can do is protest.”

The Final Hope

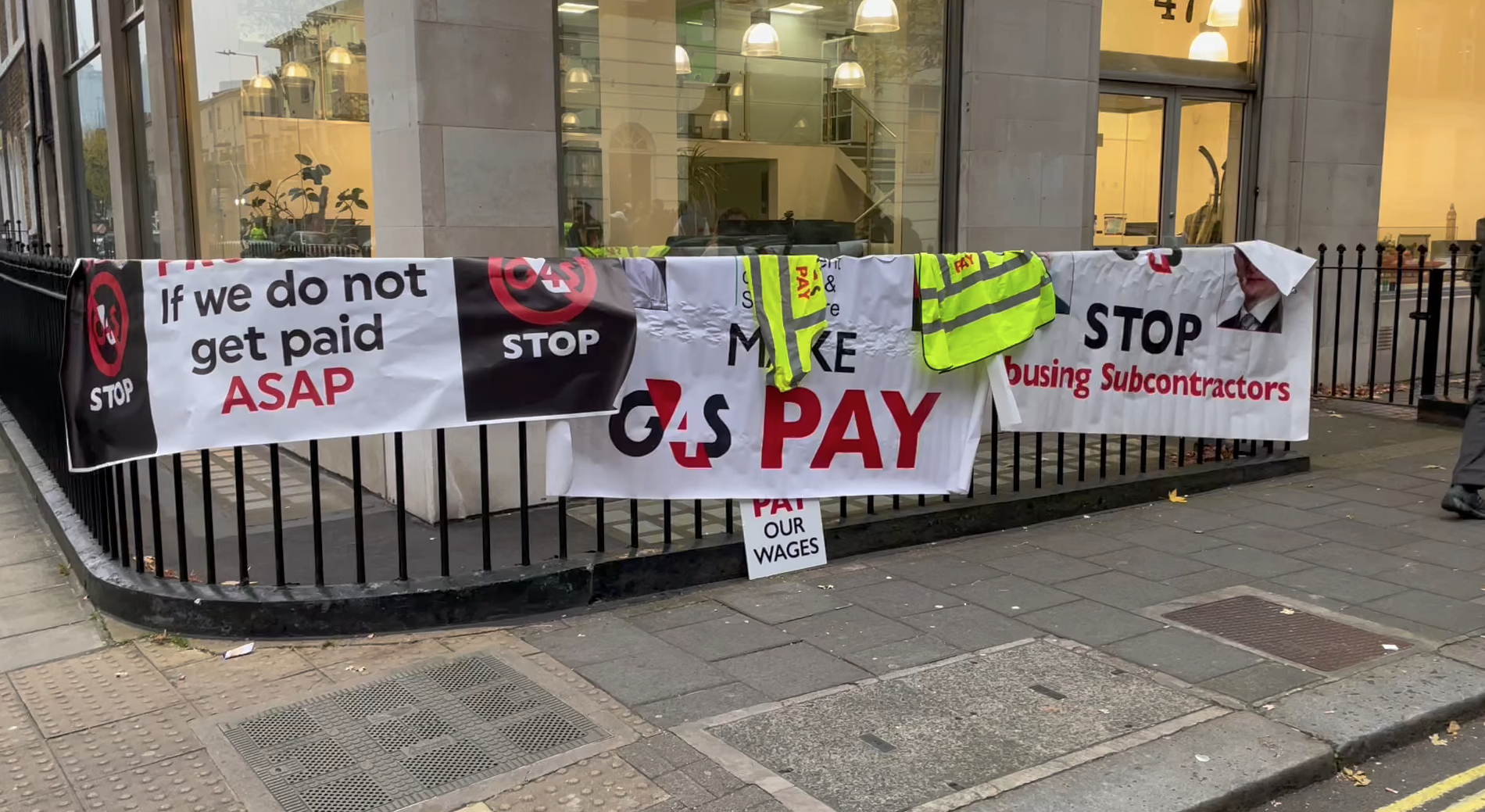

Multiple protests, organised through word of mouth and without any central leadership, have taken place outside G4S’ head office in central London since September.

Dozens of people clustered onto the pavements and shouted up into the glass-fronted building. Occasionally, cars driven by G4S office workers emerged from the building, and protesters would rush to hold up banners displaying slogans like, “Pay Our Wages”, while chanting “Who is responsible? G4S!”.

"I feel like a beggar who has come on the street for his own money", says Imran, who worked at Heathrow Airport's Crowne Plaza hotel.

"I feel like a beggar who has come on the street for his own money", says Imran, who worked at Heathrow Airport's Crowne Plaza hotel.

Several attendees of a protest outside G4S’ headquarters in Pimlico claimed to have received calls from no-caller ID numbers where they were warned against attending future protests.

“After a few protests, I got a phone call from an unknown number telling me to stop protesting and that there would be trouble if we continued”, said *Zafar, a British Pakistani from London, who worked 12-hour shifts for £8 an hour in multiple quarantine hotels between June to October 2021, including Park Plaza, Millennium Hotel and Holiday Inn branches.

Khawaja, who worked for quarantine services at Heathrow Airport between February and October received a similar unidentified call. He said that the caller assured him that there was no need to attend further protests, as he would receive the money by the end of the day. The money never materialised.

Many, like Zafar and Khawaja, has been recruited by the same contractor. The name ‘AKD’ cropped up over and over again, and everyone’s experience with them ended the same way.

By November, phone numbers that previously worked for AKD Facilities Management were seemingly no longer in service, while the majority of emails and texts went unanswered.

Supreme Security now appears equally impossibly to reach. When attempting to call the numbers of other contractors such as Supreme Security, the numbers provided on its website were not recognised or immediately disconnected .

The Quarantine Hotels

Recruits were often deployed across multiple quarantine hotels over a period of several months. This map depicts some of those identified in London by interviewees.

The Outsourcing Giant

G4S relies on a complex web of subcontractors to recruit its security officers for quarantine hotels.

Companies such as AKD Facilities Management, Supreme Security, Counter Security and KK Security secured many hundreds of workers for the quarantine hotels on salaries averaging around £8-9 an hour. Some of these companies were themselves contractors of larger firms. In fact, security officers were often two or three companies away from G4S in the supply chain.

Complicating things even further, several security officers claimed they had received payslips from employers such as AKD with names on that they did not recognise, indicating that all was not as it seemed.

“Payslips from AKD showed names that I’d never heard of”

The lack of transparency comes as no surprise. A Guardian investigation published in May 2021 revealed that G4S supply chains involved small and opaque firms that paid recruits working across the NHS test-and-trace services.

These firms fitted the pattern of mini umbrella companies (MUC), according to the investigation. MUCs essentially allow employers to avoid contributing national insurance, which costs the taxpayer hundreds of millions each year

In response to The Guardian’s findings, a G4S spokesperson said:

“When this practice came to our attention, HMRC was notified and we have taken decisive action to ensure that all our agency workers are employed directly by the approved company, and not via a subcontractor.”

However, claims from quarantine hotel workers that payslips had different and unusual names suggests this practice is still taking place.

When approached about the missing payments, a G4S spokesperson said:

“In the case of certain suppliers, delays in providing G4S with the required information means that the invoice verification process has been delayed”.

While G4S didn’t expand on what they meant by ‘required information’, recruit after recruit recounted the same experience. None of their contractors had required them to provide their national insurance number or legal documentation before or shortly after commencing work at the quarantine hotels.

“It was clear they wanted us to start working as soon as possible, and important processes were left out because of that. All I had to do was show my SIA badge on arrival and then I started immediately,” says Sajjid.

He was contracted by Supreme Security Services, to work as a team leader security officer at Arora Hotel’s Gatwick branch between April and October.

Before taking up the quarantine hotel work, Sejjad worked as a baggage handler at Gatwick airport, however, once COVID-19 hit and travel restrictions came into effect, he was forced to find another job. “I wasn’t asked for any of my details, such as my passport or national insurance number until very recently. This should have been done at the very start and G4S should have ensured this happened. Now, because of all this chaos, people are suffering.”

Whether or not G4S was directly aware of the fact subcontractors had failed to collect the relevant information is unclear, however, for some, it's a simple answer. “G4S must have known earlier this year that AKD had not verified our legal documents as they had issued us with a reference number,” says Zafar.

Chaos, repeated

G4S’ handling of the ‘required information’ echoes its 2012 Olympic security preparations.

Tim Steward, who was recruited by G4S as a team leader, told The Guardian that he had provided documentation for vetting to G4S, only to be told later on that they did not have the information on record. Other guards spoke of being offered shifts after they had failed G4S own vetting.

Quarantine hotels workers such as Zafar, Sejjad, and Khawaja, all say they immediately provided the ‘required information’ –specifically, their national insurance numbers – but have yet to be paid the full amount owed.

For many, however, when the time came to provide the ‘required information', this might have proved impossible.

Abid* moved from Pakistan to the UK in 2020 to study microbiology. He is allegedly now owed two months wages amounting to £5000 after being recruited by KK Security in July 2021 to work as a security officer at a Holiday Inn branch outside of Heathrow Airport.

“Many people working in these hotels at the time were on student visas and working way beyond the 20 hours permitted,” says Abid.

If recruits were being hired without having to provide any clear documentation, it raises questions as to whether such individuals were legally permitted to work at quarantine hotels.

According to G4S, subcontractors such as AKD, Supreme, Counter, and KK Security were all approved by the Department of Health and Social Care. This too raises serious questions on the quality of due diligence processes carried out by DHSC and whether the recruitment methods used by approved subcontractors were adequately assessed.

Since September, several meetings between G4S and subcontractor managers have allegedly taken place.

As of late December 2021, recruits were informed by AKD that G4S had "agreed to pay 30 percent of the wages owed, followed by another 20 percent after 12 months".

However, according to G4S, there was no such agreement. In a statement to the claims made in this article, G4S said:

"All payments due to these security subcontractors were completed in December 2021.”

Why subcontractors such as AKD refuse to pay their employees in full when they have allegedly received the money remains unclear. None of the companies contacted responded to emails or calls.

Meanwhile, the Department of Health and Social Care has since awarded G4S a contract worth £1.1 billion to continue providing these services across London, and regions across east and southeast England between September 2021 and March 2022.

Hotel quarantine recruits also say that despite not being paid missing wages, they are now being offered shifts by the same subcontractors who are likely being used by G4S under the new contract. And so, the cycle continues.

The Big Picture

The issue of missing payments to hotel quarantine workers highlights yet another case where workers in insecure positions have not been paid the full or correct wages.

A report published by London-based labour exploitation charity, FLEX, in October 2021 looking at the experiences of low-paid and insecure workers during the pandemic revealed that 44 percent of respondents had not been paid full or correct wages at least once since March 2020.

This is supported by Citizens Advice, which found that insecure workers were three times more likely not to be paid the wages they were owed compared to the rest of the working population.

“The risks of exploitation or unfair treatment is often connected to workers on some kind of temporary contract”, says Klara Skrivankova, a grants manager at Trust for London, a charitable foundation that looks at issues of poverty and inequality in London.

Klara Skrivankova, Trust for London

Klara Skrivankova, Trust for London

Klara notes that employers will often pay the money owed once a worker has received professional advice, but it’s increasingly difficult for people to access their rights and entitlements

Legal aid services have been stripped back by successive cuts in recent years, leaving people in low-paid and insecure jobs who don’t have the financial means to secure legal advice increasingly vulnerable to exploitative practices.

"The fact employers pay the money that is owed once an organisation such as an NGO intervenes is a clear indication they believe it's possible to get away with exploitative practices"

While G4S has a code of conduct for suppliers in place, the missing payments to hotel quarantine workers raise questions over how effectively this code is being followed and, crucially, protected by G4S.

“Even with the best policies and due diligence processes, you cannot guarantee that there won’t be issues with exploitation in a supply chain," says Klara. "The question is what are the measures a company has in place to reduce that risk and how do they respond when a situation arises.”

For hotel quarantine workers who continue to wait for missing wages to pay overdue rent and credit-card debts, these measures have ultimately failed them.

People like us are just getting neglected, says hotel quarantine worker, Saima.

People like us are just getting neglected, says hotel quarantine worker, Saima.

What remains is an overwhelming sense of neglect for many such as AKD security officer Saima, who worked countless hours in frontline conditions at the height of the pandemic.

Image credits: Wikimedia, isoformLLC, booking.com, Lewis Clarke, Duncan Rawlinson.

*Some names have been changed to protect identity.