The growing influence of Saudi Arabia on the Premier League

How Saudi Arabia is continuing to affect the English top-flight

Photo: Mehdi Bolourian

Photo: Mehdi Bolourian

Photo: @fabrizioromano (Twitter/X)

Photo: @fabrizioromano (Twitter/X)

Photo: Mehrdad Esfahani/SNN

Photo: Mehrdad Esfahani/SNN

On 3 September 2023, Liverpool star Mohamed Salah poked the ball into the back of the net, securing a comfortable 3-0 victory at home to Aston Villa. It was by no means the most impressive goal of the Egyptian star’s illustrious six-year stint at Anfield, but it was another telling reminder of the world class pedigree he brings to the club.

More significantly, it was a reminder as to why the club had chosen to reject an eye-watering £150 million bid from Saudi Arabian club Al-Ittihad just a few days prior. Yet with talk of the Saudi Pro League (SPL) club preparing to make an improved offer of up to £200 million, before their deadline day shut on 7 September, it signalled the growing influence the Middle Eastern country continues to impose on the beautiful game.

Salah is still, of course, a Liverpool player, but the Saudi Pro League has already turned heads with recent marquee signings. The most recognisable of them all, Cristiano Ronaldo, might be heading towards the twilight years of his career (although still surpasses expectations at the age of 38 as 2023’s top goalscorer), but it signified a huge statement when he signed for Al-Nassr at the tail-end of 2022.

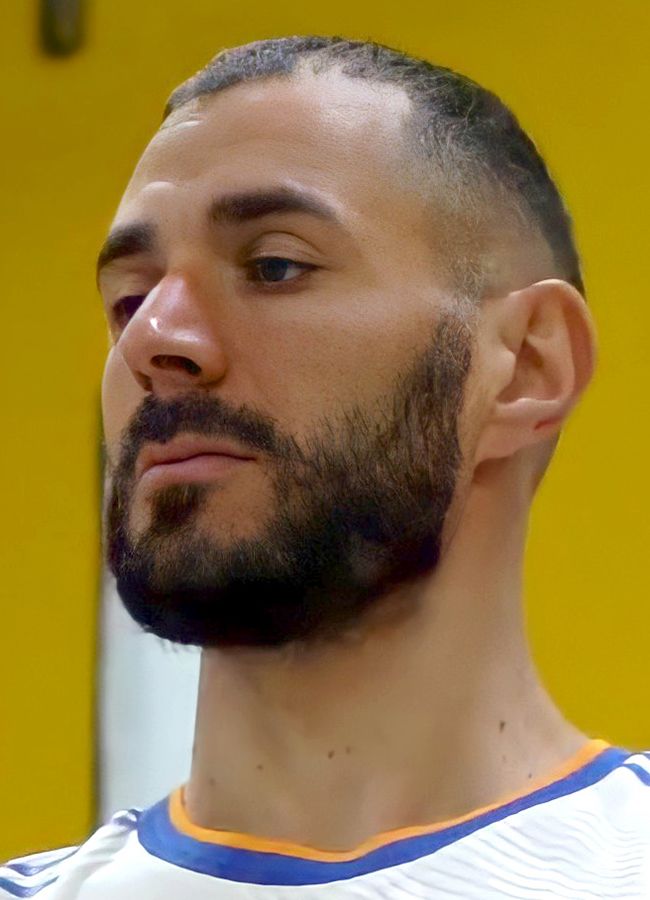

In fact, Ronaldo’s move marked a watershed moment for the league, with other big name signings following. Unlike Salah, Liverpool captain Jordan Henderson made the move from Merseyside to the SPL, signing for Al-Ettifaq, whilst global superstars Karim Benzema and Neymar swapped the grandeur of Real Madrid and Paris Saint-Germain, respectively, for Saudi Arabia’s increasingly-ambitious league.

And it’s not just players in the final stages of their football careers who have decided to make the move, either. Rúben Neves and Allan Saint-Maximin, both aged 26, and 29-year-old Aleksandar Mitrović were among the best players at their Premier League clubs before heading to Saudi Arabia to ply their trade; moves which bucked the trend of it being older players seeking football in less competitive leagues.

For many football fans, the world’s most popular sport is a chance to escape from politics and the challenges of the world. But when it comes to the growing influence of Saudi Arabia on football, and specifically the Premier League, there is far more beyond the on-pitch antics – and it proposes an unfolding economic and geopolitical situation that will have long-term ramifications for the game.

Photo: Real Madrid

Photo: Real Madrid

Photo: Steffen Prößdorf

Photo: Steffen Prößdorf

Photo: مقداد مددی

Photo: مقداد مددی

What are the criticisms?

On 7 October 2021, it was officially announced that Newcastle United F.C. was under new ownership. A consortium of the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), the investment firm PCP Capital Partners (run by British businesswoman Amanda Staveley) and billionaire brothers David and Simon Reuben were now at the helm of one of the Premier League’s best-loved clubs, which formed more than 130 years ago.

The deal, worth a reported £300 million, saw previous owner Mike Ashley – the controversial businessman and Sports Direct owner – sell 10% of the club to both Stavely and the Reuben Brother’s firms each, whilst the remaining 80% went to PIF, the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia. A new chairman was appointed: Yasir Al-Rumayyan, who is also the governor of the PIF.

But why does this takeover matter? Was the Premier League not already a hugely wealthy venture, used to this sort of investment? And isn’t such investment in one of the Premier League club’s most well-known sides in a major Northern city not a wholly positive thing?

Photo: Ardfern

Photo: Ardfern

Upon the news, the Premier League issued a statement saying that despite the PIF’s majority stakeholding in the club, they were satisfied they had “now received legally binding assurances that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia will not control Newcastle United Football Club”. But with the approximate £538 billion PIF fund belonging to the Saudi Arabian government, and being controlled by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, many are not convinced.

What’s more, Saudi Arabia’s long list of reported human rights violations, of censorship and attacks on women’s rights, has caused the most ground for concern, calling into question the integrity of the sport. If football, and sport in general, has always aspired to bring out the very best of human nature – of teamwork, dedication and respect – then its ties with a country that operates such abusive practices threatens to undermine the game altogether.

Newcastle United is one example, albeit of major economic significance. There is every reason to believe Saudi Arabia’s influence on the Premier League won’t stop there. And with the country set to host the World Cup in 2034, having been confirmed as the sole bidder for the position, many commentators deem its positioning in the world of football as a prime example of ‘sportswashing’.

Below, The Times’ Sports Writer Alyson Rudd (speaking in late November), discusses the impact of the PIF-backed consortium’s purchase of Newcastle United; why the new owners are exceptionally eager to abide by financial fair play regulations, especially in light of investigations into Manchester City; and the overall impact of Saudi-backed clubs on the Premier League transfer market.

Alyson Rudd, Sports Writer, The Times

Alyson Rudd, Sports Writer, The Times

What is ‘Sportswashing’?

Within email exchanges between the UK Foreign Office and the Premier League regarding the PIF-backed consortium’s takeover of Newcastle United, uncovered by The Athletic through a freedom of information request, a note from the government department reads: “The takeover of Newcastle presents an opportunity to promote a different image of Saudi Arabia in the UK.”

Whilst the UK government has a complex relationship with Saudi Arabia, often supporting its geopolitical aims and defence and security matters (since March 2015, according to CAAT, the UK has supplied £8.2 billion worth of arms to the country), the Saudi’s human rights abuses are still well-known.

The Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International are unanimous in their assessment of state suppression in Saudi Arabia; and in their criticism of the country’s male guardianship system, which requires women to obtain male guardian permission to get married, leave prison and obtain some forms of healthcare; as well as its use of the death penalty, which in March 2022 culminated in the execution of 81 men – one of the largest mass executions in the country in decades.

Yet by increasing investment in, and diverting attention towards, sports – especially football, both Saudi Arabia and the world’s most popular sport – the theory is these issues can be deflected both internally and on the international stage.

Explaining the term ‘sportswashing’, Professor Jules Boykoff, an expert in sports politics at Pacific University and a former professional footballer himself, said: “Sportswashing is when political leaders use sports to try to appear important or legitimate on the global stage while stoking nationalism and deflecting attention from chronic social problems and human-rights woes on the home front.

“Sportswashers try to increase national prestige and to convey economic or political advancement. One key point that a lot of people miss is that sportswashing can emerge in both authoritarian and democratic political spaces. Also, sportswashing involves multiple audiences, both international and domestic; sportswashing can target a country’s internal population as much as an external, global public.”

He added, in no uncertain terms: “Saudi Arabia is a quintessential purveyor of sportswashing in the 21st century.”

Professor Simon Shibli, director of the Sport Industry Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University, meanwhile, concurred with the sentiment that ‘sportswashing’ “is used to describe the practice of nations seeking to repair damaged reputations through hosting sports events or otherwise investing in sport.” He cited the Beijing Winter Olympic Games 2022 and Qatar FIFA World Cup 2022 as such examples. (The likely prospect of a 2034 Fifa World Cup in Saudi Arabia would be another such event).

However, he added: “There is a thin distinction between ‘sportswashing’ and ‘soft power’. My view is that what is happening with sport in The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is more about building soft power and achieving the goals of Vision 2030 than addressing perceived reputational damage.”

Below, Alyson Rudd further explains the term ‘sportswashing’ and how it compares to other previous major investments in the Premier League; and why she always makes a point as a journalist to mention ‘sportswashing’ when she discusses Saudi Arabia.

Alyson Rudd, Sports Writer, The Times

Alyson Rudd, Sports Writer, The Times

Vision 2030

The Vision 2030 initiative Shibli is referring to is a key government program launched by the Saudi Arabian government in January 2016. Whilst its official intentions are broad and wide-ranging – revolving around three pillars of creating ‘a vibrant society’, ‘a thriving economy’ and ‘an ambitious nation’ – many deem its aims as much more obvious: to move the country away from its unsustainable reliance on fossil fuels. (In 2022, oil still accounted for 40% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP, according to the IMF).

As Boykoff explained: “With a fossil-fuel-driven economy in an age of climate change, leaders in Saudi Arabia have recognised that they need to diversify the country’s economy. In addition, as [Mohammed bin Salman, Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia] tries to lure home highly-educated Saudi nationals living abroad, cultural products like sport and music can be effective.

“This is a concerted plan with multiple audiences: it lets the world know that the country is an important newcomer in world soccer, but it also lets domestic populations know that big changes are afoot, and that Saudi Arabia is emerging as an important power broker in global cultural affairs.”

Indeed, within the 84-page Vision 2030 document, under the pillar to establish ‘A Vibrant Society’, there is an acknowledgement that “opportunities for the regular practice of sports have often been limited” within the nation previously, but that “this will change” and that the country now “aspire[s] to excel in sport and be among the leaders in selected sports regionally and globally.”

No doubt such a pursuit is a positive one, as is the intention “to encourage widespread and regular participation in sports and athletic activities,” recognising that “a healthy and balanced lifestyle is an essential mainstay of a high quality of life.” But with ‘sportswashing’ in mind, there is a clear subtext: to use sports as a vehicle to demonstrate positive social change, masquerading over societal ills.

Shibli added that it is football in particular that offers a means to ‘sportswash’, in a manner nothing can rival. He said: “The PIF has significant shareholdings in household names like Disney, Uber and Boeing, amongst many others. None of these investments generate much in the way of publicity or brand equity, but football specifically and sport generally are different. Football is a global industry with unparalleled profile and public interest which KSA hopes to harness to further its Vision 2030 goals.”

NUFC Fans Against Sportswashing

One group with a clear stance against Saudi Arabia’s growing influence in football is NUFC Fans Against Sportswashing, a group set up by Newcastle United fans just after the sale of the club in 2021.

John Hird, co-founder of NUFC Fans Against Sportswashing, said: “Almost the day the announcement was made that [Mike] Ashley was gone, we managed to get in contact with people who felt the same; those who didn’t want one of the bloodiest dictatorships in the world to take on Newcastle.”

“We were happy that Ashley was kicked out,” he added. “We once had a march outside Ashley’s Sports Direct shop in Newcastle over zero-hour contracts, and even some unions got involved. I remember feeling quite proud of that, being from the northeast. One of the things we said in our first meeting was that if we can protest against that, then surely for [Saudi Arabia’s] beheading of young people for made-up crimes, or for putting young women in prison for Tweets, we should be able to say something about that. That was basically the motivation.

“We have to be honest, the job the Saudi state wanted to do was to use Newcastle to divert attention. And they’ve done it. If we didn’t speak up – because we get told to shut up quite a lot – nobody else would be raising it. We think there should be people who should know better, like MPs in the Northeast, councillors and official supporters, they should be raising these issues.”

The group has around 7,300 followers on Twitter/X, which may not appear substantial (it would cover just 14% of Newcastle’s 52,000-capacity St. James’ Park), but it is still making an impact with fans – even if some, including many Newcastle fans, oppose their views. They hold regular meetings, run a fanzine and have spoken with national outlets like The Guardian and Channel 4, all to spread their key message: Saudi Arabia should not be involved in Newcastle United.

“Most fans just say, ‘Well, what can we do? What’s the alternative? But we want [the PFI-led consortium] out. We don’t think nation-states should own clubs,” John said. “But where I would put the responsibility – and what we keep coming back to again and again – is with MPs, Newcastle MPs, councillors (70-odd of them), fanzine editors, who all said they would keep talking about human rights. And the sad truth is: since the takeover, none of them have actually raised human rights.”

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

Photo: @NoSaudiToon

In what John describes as the “battle for hearts and minds” over the issue, the group invited Lina al-Hathloul to Tyneside in September, to speak about the subject. Lina is a leading Saudi human rights activist, and the sister of Loujain al-Hathloul, a Saudi women’s rights activist and political prisoner who led the movement to allow women to drive in the kingdom before being arrested and detained.

John outlined how Lina’s visit proved the reticence from UK officials to criticise the Saudi government’s involvement in Newcastle United – a silence which is one of the key steps in ‘sportswashing’.

“She came to Newcastle and wrote to all the MPs in the northeast, and all the councillors, asking to meet. We had a meeting; I was there, and there were two Liberal Democrats and one Labour [councillor]. Lina said, ‘If I’d come here five years ago, campaigning on human rights, I would have had meetings all day. What are you scared of? Is democracy so cheap? £500 million buys the silence’.

“I’m not blaming the fans for that, you’ve got to blame the people who represent them. It’s disgraceful. [Lina] made the point that if in two years the [Saudi government] can achieve that, what happens when the Saudi regime starts buying [UK] newspapers?”

NUFC Fans Against Sportswashing also makes clear that the on-field game of football itself is becoming a victim of nation-state ownership, losing its identity and integrity. “We feel like we’re at a bit of a crossroads in football. Where’s it going to go next?

“With all the whataboutery – what about Man United, for instance; if I was a Man United fan I’d be against [their owners] The Glazers as well – we’re giving a pause for thought to say: ‘Which direction is football going to go in now?’ If it just becomes a plaything for multinationals and nation states, it ceases to be a sport.”

Financial impact on the game

Alyson Rudd, Sports Writer, The Times

Alyson Rudd, Sports Writer, The Times

Above, Alyson Rudd concludes by discussing the long-term impact of the renewed focus in football from the Saudi Arabian government; how that has impacted the transfer market for the 2023/24 season already and what the opportunity represents to players, even if that "skews the market".

The Premier League is almost unanimously considered the greatest football league in the world. Among the many qualities that makes it so attractive (and lucrative) is its competitiveness. In Deloitte’s Football Money League 2023 report, more than half (16) of the world’s top 30-ranked clubs were from English football’s top division, which in itself accounts for 80% of the Premier League.

What’s more, on any given match day, surprise results are almost paradoxically regular. The likes of mid-table Brentford can beat Champions League winners Man City home and away, whilst relegation contenders Nottingham Forest can secure a victory over title-chasers Liverpool – both of which happened last year. Leicester City famously won the Premier League in 2015-16, despite being 5,000/1 to do so at the start of that campaign.

And whilst the Premier League has long-been a benefactor of wealth, there are concerns that the increasingly vast sums being added into the game through Saudi Arabia and the PIF are likely to disrupt how it operates in the UK and wildly skew the transfer market for players.

As John, a lifelong Newcastle United fan, added: “It’s a cliche but it’s true: sport has to have a level playing field. And if you don’t have a level playing field, it ceases to be a sport. If you have nation states owning football clubs, that takes them onto another level, it could end up like La Liga – where it’s just Barcelona against Real Madrid. It’s boring.”

Premier League transfer spending by season

Many fans would recognise that the Premier League has long had disruptive billionaire owners already. In June 2003, Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich took over Chelsea, with the club going on to win 18 major trophies (including five Premier League titles) during his reign, which ended in early 2022 due to the fallout of the war in Ukraine that saw the UK government freeze his assets.

In an even more similar blueprint to the takeover of Newcastle United, Manchester City have been fully owned by Sheikh Mansour since 2008. Mansour is the Vice President of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and a member of the ruling family of Abu Dhabi. His brother, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyanda, is the UAE President.

Man City’s ownership has brought considerable wealth and success to the club, seeing the team, now under Pep Guardiola’s management, win 20 trophies (including seven Premier League titles) in 15 years. But their spending power has arguably come at a cost, with the Premier League investigating Man City for more than 100 breaches of financial fair play rules at present.

When it comes to Saudi Arabia’s footballing aspirations, they do not necessarily view a level playing field as being in-line with their aims. In June 2023, the Saudi Press Agency and Saudi Arabia Ministry Of Sport announced a major new shake-up to its footballing world, all in-line with the nation’s Vision 2030 aims. Under the Sports Clubs Investment and Privatisation Project, a mix of public-private investment would allow for a greater influx of wealth into the Saudi Pro League, which would be “supported in its ambition to be amongst the top ten leagues in the world.”

This support has meant the spending power of the Saudi Pro League far and away outweighs its revenue. Only the Premier League spent more money than it raised through revenue in the 2022/23 summer transfer window, but its income accounts for around half (54%) of its spend. In the Saudi Pro League, however, revenue accounted for less than 7% (6.8%) of spend. In other words, the Saudi Pro League has spent almost 15 times what it’s earnt so far this year – a situation that can only be sustained by the backing of the PIF.

Spending and income from the 10 largest leagues

Furthermore, as part of the recent plans for football in Saudi Arabia announced in June, the PIF announced it was taking control of four teams in the Saudi Pro League: Al Ahli, Al Ittihad, Al Hilal and Al Nassr, the latter of whom had already signed Cristiano Ronaldo some six months prior.

Photo: محمد امین انصاری

Photo: محمد امین انصاری

Photo: Mehdi Marizad

Photo: Mehdi Marizad

Photo: Ambatukamahhh

Photo: Ambatukamahhh

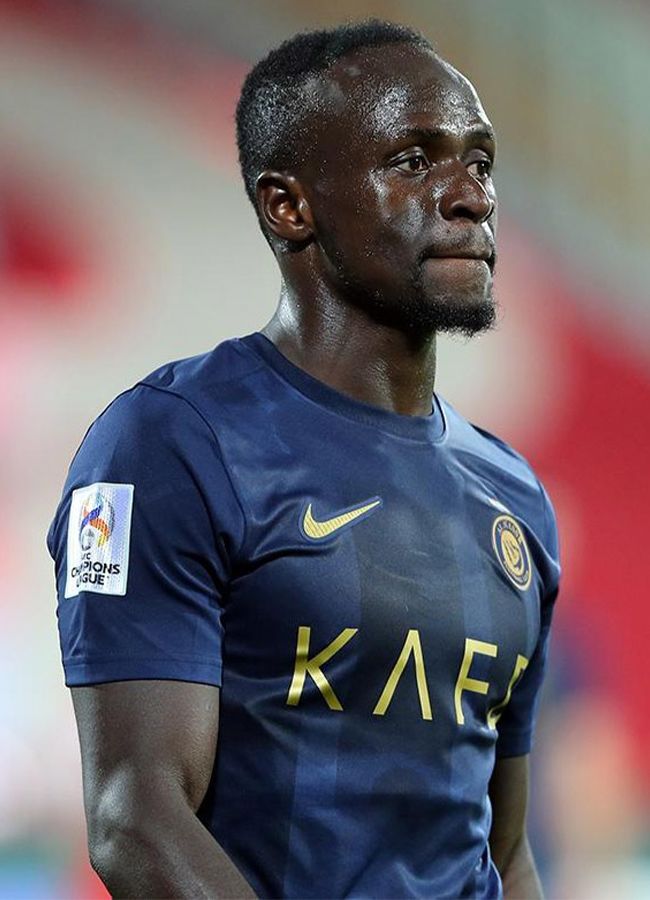

This paved the way for a rapid push to elevate the Saudi Pro League, first achieved by the most obvious method, as stated by Prince Abdullah bin Turki Al-Faisal, the Saudi Arabian Minister of Sport: “bring in the world’s top players.”

For the 2023-24 season, this meant each of the four PIF-owned teams targeted “a minimum of three internationally renowned players,” whilst a smaller number of these top players were set to be “distributed among the other teams in the league.”

The result led to the spending of these four teams far exceeding the league’s other clubs. In fact, according to Transfermarkt data, in a league of 18, these four clubs accounted for 87 percent of the total expenditure by the Saudi Pro League at the start of the 2023/24 season (during its transfer window between 1 July and 7 September 2023). Al Hilal’s net spend of £302.1 million alone was more than any other team in the world last summer.

Spending breakdown of Saudi Pro League clubs in summer 2023 transfer market

Of course, there’s a lot the Saudi Pro League is unable to presently offer players. The league itself is deemed far less competitive than others (data company Opta ranked it 27th out of 30 for best leagues in the world as recently as September), and European players at big clubs are especially reluctant to give up contending in European football, including the coveted Champions League.

But the sums of money that have attracted players so far are staggering; so large they make the wages of Kevin De Bruyne, the Premier League’s current highest earner on £400,000-a-week, look paltry. Ronaldo, for instance, is on a reported £3.3million-a-week deal, whilst Karim Benzema and Neymar take home £3.23million and £2.6million a week, respectively.

Even players whose performance levels were starting to worsen in the Premier League are earning far more than those who remain in the English top-flight, like 33-year-old Henderson on a reported £700,000-a-week; Kalidou Koulibaly, meanwhile, a centre-back who struggled to make much of an impression at Chelsea is on £577,000-a-week.

Highest-paid players (Premier League vs. Saudi Pro League)

Of course, given this renewed strength in the Saudi Pro League’s purchasing power has only been demonstrated for one full transfer window – the only full window in which the PIF have owned four Saudi clubs – it is too early to say to determine its full effects.

But with around 27 internationally renowned players having already signed for Saudi clubs, as the league continues its pursuit to be a top 10 league in world football, under the wider Vision 2030 plans, their influence has really just begun. It perhaps comes as little surprise that one of the next big stars touted to make the move to the SPL is the Premier League’s highest-paid player, Kevin De Bruyne.

On this matter of the SPL’s disruption, Boykoff is clear about the impact this will have on the Premier League, especially when it comes to players who aren’t simply heading towards retirement. He said: “If the league continues to thrive and receive strong state support,” he says, “there is a chance that it will drain some of the top younger players from the Premier League and other leagues around the world. It’s just a cold-blooded matter of money.

“On this front, keeping a close eye on younger players is important. Players in the twilights of their careers have long moved to less-competitive leagues to stretch out their money-making days, but players in their prime are a different matter. They could not only improve the quality of the league but also signal to other top younger players that the Saudi Pro League is worth their time.”

Photo: Happiraphael

Photo: Happiraphael

Photo: Кирилл Венедиктов

Photo: Кирилл Венедиктов

Photo: Mehrdad Esfahani/SNN

Photo: Mehrdad Esfahani/SNN

Boykoff added: “In the end elite athletes are motivated by being successful at the highest level rather than solely by money. So long as Premier League players are playing in the most exciting, well-supported league and can play in prestigious European club competitions, money alone will not change that. There will probably be increasingly closer ties between the two leagues, which will help to achieve the ‘soft power’ which is so important to Saudi ambitions.”

However, Shibli is also clear that money alone can’t buy success. “In the long-term the SPL may well become a dominant league in Asian and/or Arab footballing terms, but I doubt that it will ever seriously threaten the PL.

Shibli is even more candid about the impact, and what the Premier League is likely wary of. “It is not difficult to appreciate why the existing market would be nervous about a new entrant with pockets so deep it could disrupt the industry.”

The influence of Saudi Arabia on the Premier League is more than a matter of two sides vying to score more than the other for 90 minutes. It’s a matter of money, ethics and geopolitics. It might be known as the beautiful game, but football suddenly has an ever-growing complexity – and, many argue, an increasingly ugly side – to its game.