The Rise of Intensive Poultry Farming

Every seven weeks, a lorry carrying 260,000 chicken eggs winds its way through the remote flint-stone villages of west-Norfolk before turning down a long nondescript driveway to Whin Close Poultry Farm. The eggs are then placed into eight 300ft x 66ft corrugated iron sheds heated to precisely 36°C. When they hatch three days later, a finely tuned 38 day programme ensues. Every aspect of the environment, from the humidity to the number of daylight hours is meticulously controlled for optimum growing conditions. Within this time some 10,000 birds will die due to heat stress, disease, or injury, but the rest will continue growing rapidly until they reach the slaughter weight of 2.5kg. On day 38, several lorries will return to Norfolk and transport the birds to Cranswick processing plant in Suffolk, which produces 1.4 million chickens a week for British supermarkets.

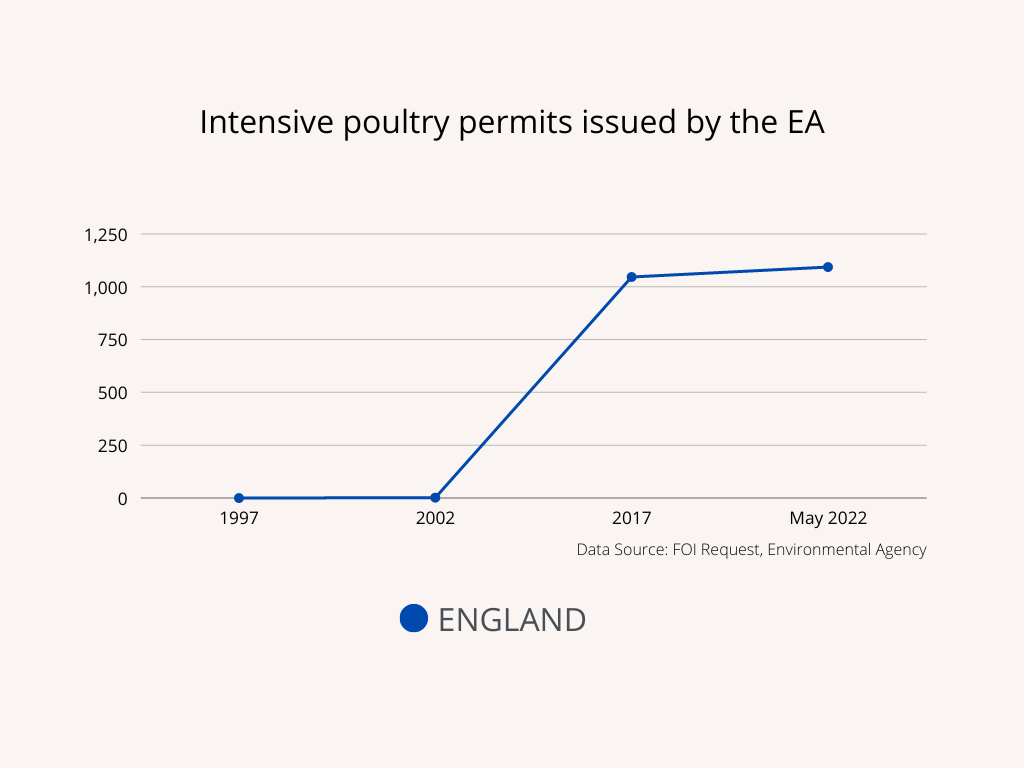

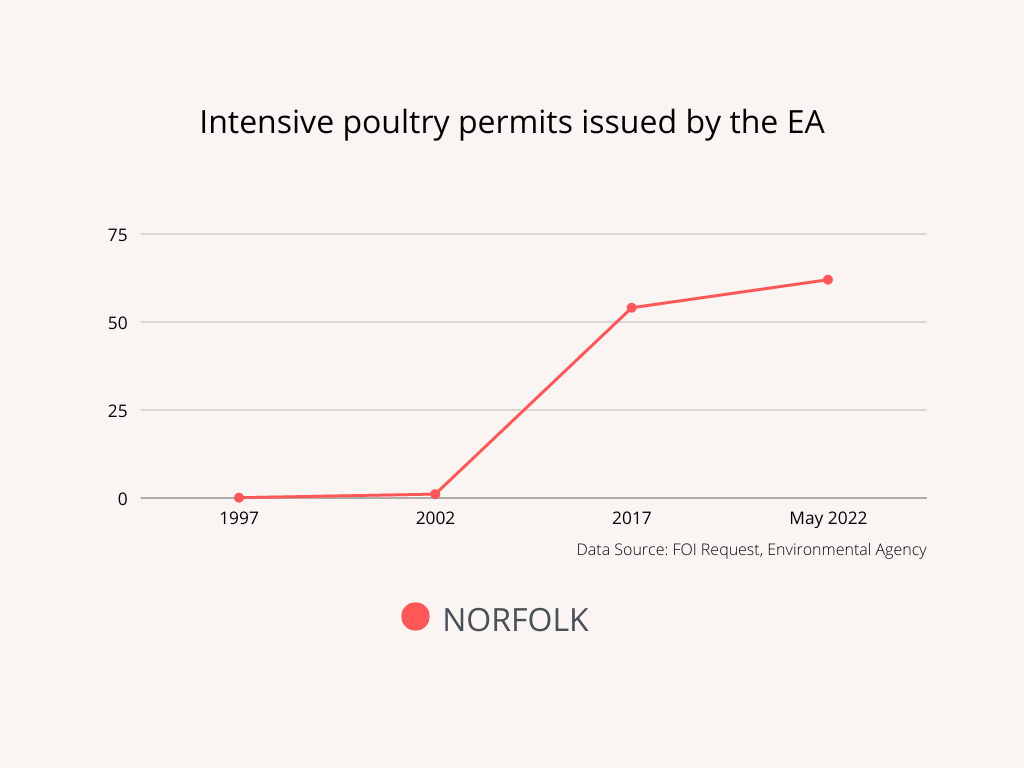

Whin Close Poultry Farm is one of the many new intensive poultry units dotted across the countryside growing broilers, chickens reared for meat, for the UK’s booming demand. Whereas 70 years ago the average Brit ate an astonishingly modest 1kg of chicken a year, today most British people consume on average 25kg of chicken annually. To feed our growing appetite, new intensive poultry farms have been cropping up all over the countryside. In fact, in the last 20 years the UK went from having just 2 intensive poultry sites to over 1000 today.

For many farmers, starting an intensive poultry site is an attractive prospect. Unlike crops, poultry offers a steady income that doesn’t rely on favourable weather nor a great deal of labour. For William Barber, owner of Whin Close Poultry Farm, chickens could also save him money, as he could use the manure they produce to fertilise his 3000 acre arable farm.

But out in England’s green and pleasant pastures, new intensive chicken sites can be enormously controversial. Whilst farmers say they are led by increased demand, those in opposition say they blight the countryside and subject chickens to a miserable existence.

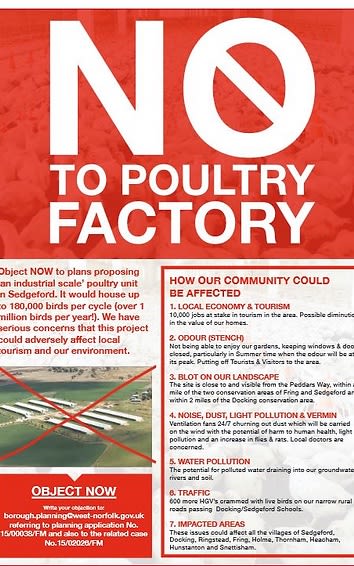

When William Barber submitted plans for his £1.5 million poultry farm in 2015 thousands rallied behind a campaign to stop it from going ahead.

“Truth was the first casualty," said William.

“People were being told the stench would cover an area the size of Birmingham and 10,000 jobs were at risk,” he added.

Hundreds joined the Say No to Poultry Campaign which had the support of the Norfolk tourism industry and an international vegan charity. credit: Whin Close Poultry Farm

Hundreds joined the Say No to Poultry Campaign which had the support of the Norfolk tourism industry and an international vegan charity. credit: Whin Close Poultry Farm

William remembers how at one council meeting, a mother burst into tears fearing her baby would die from the level of toxic ammonia emanating from the site.

“They had scared her so much with misinformation, it simply wasn’t true,” he added sympathetically.

Even his wife Louise was beginning to be ignored by members of the congregation at the village church. To gain the community’s trust, William only had half the sheds built. When peoples fears didn’t materialise he then built the other 4, and only received 13 objections on the second application.

Whin Close Poultry Farm was lined with trees to mitigate its impact on the surrounding landscape. credit: Whin Close Poultry Farm.

Whin Close Poultry Farm was lined with trees to mitigate its impact on the surrounding landscape. credit: Whin Close Poultry Farm.

Looking back at the battle to get his intensive farm off the ground, William thinks there was a disconnect between peoples conceptions and the reality of modern British poultry farming.

"There simply isn't enough information out there for people," he added.

In the last 6 months, another poultry site proposal has once again ruffled a few feathers.

Farmer Frederick Southgate's planning application includes eight 318ft x 72ft sheds capable of housing 350,000 birds. He believes a brown field site on his land near Attleborough, East Anglia’s poultry farming heartland, would be the ideal location.

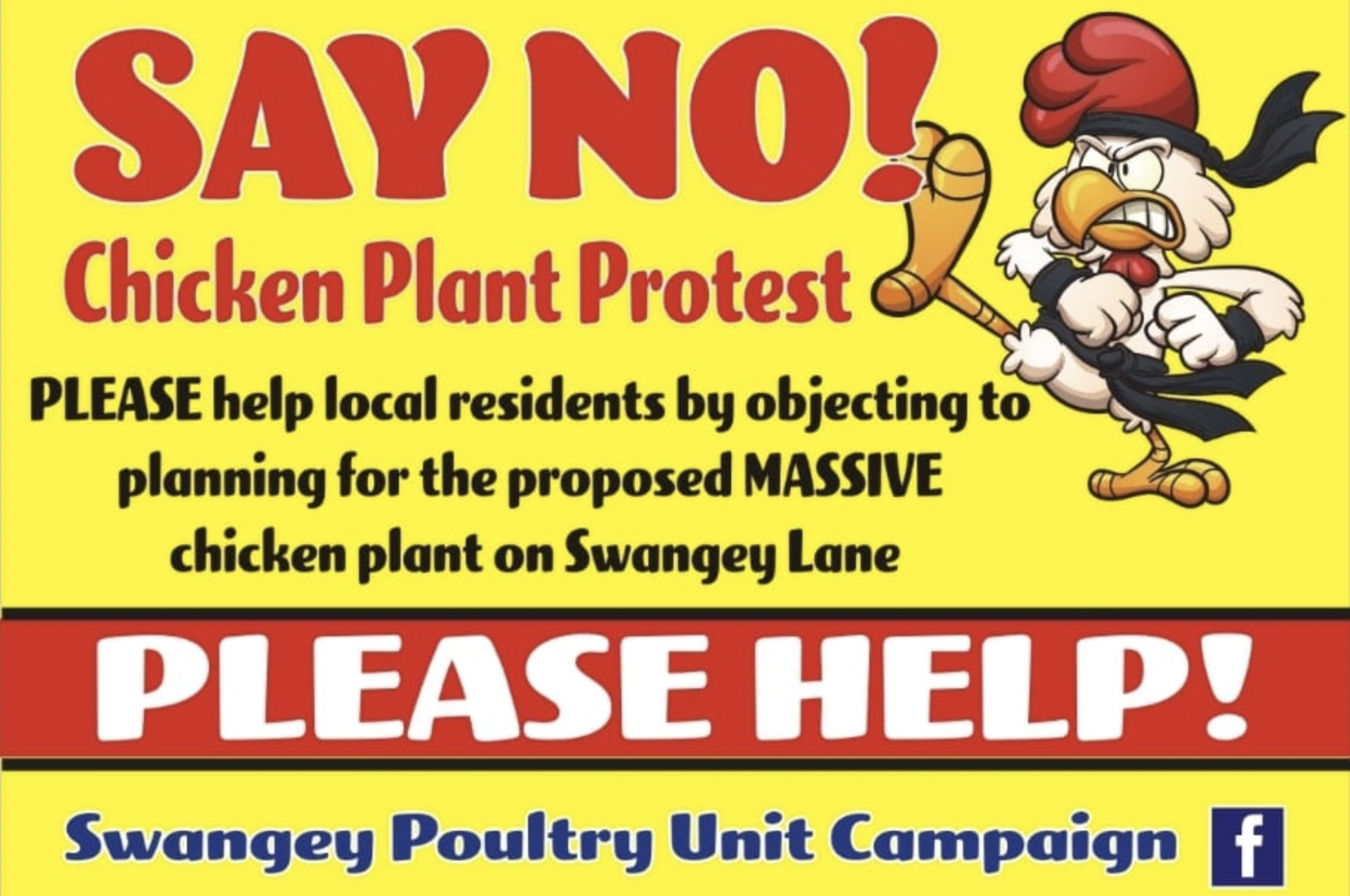

But since submission, it has received over 300 objections. Neighbouring villages have banded together and placed signs with the slogans ‘Pluck Off’ and ‘Say No’ along country lanes near the site. Parish councils and even the MP for mid-Norfolk George Freeman has condemned the application, which has already cost the Southgate family farm £65,000 in professional fees.

Residents have formed the Swangey Poultry Unit Campaign in order to fight against the proposal. credit: Frederick Southgate

Residents have formed the Swangey Poultry Unit Campaign in order to fight against the proposal. credit: Frederick Southgate

The group have placed "Pluck Off" signs on surrounding roads and outside a local school. credit: Frederick Southgate

The group have placed "Pluck Off" signs on surrounding roads and outside a local school. credit: Frederick Southgate

Many fear that surface run-off from the site containing chicken waste would threaten the ecology of nearby SSSI Swangey Fen and local fishery, Swangey Lakes.

Others, like Great Ellingham Parish Council worry that fly infestations would become more frequent and the village would be inundated with HVG’s transporting chickens all year round.

Parish council chair Tim Betts said: “To imagine that over a thousand heavy goods vehicles will be using Swangey Lane every year is frankly frightening.”

But Frederick believes many of the objections are baseless. Indeed, all flood risk and environmental assessments have approved of the plan.

Frederick’s uncle, Phillip Southgate, has farmed in the area for over 50 years. He lives within 11 yards of his own broiler site but said it barely produces any smell at at.

He added that: “No one has even had the manners to come and look at the site.

“There are some people I won’t speak to ever again over this.”

Whilst most people are concerned with the impact the farm would have on the immediate environment, others have objected on principle, against factory farming.

Vicki Tilney wrote: “These chickens should not be treated in this way.”

In a similar vein Pam Annison wrote: “I strongly object to this intensive and inhumane method of farming just to produce tasteless, plastic chicken as cheaply as possible; these poor birds never see natural daylight or breathe fresh air!”

CEO of Open Farms, Connor Jackson thinks people are right to be weary. Last year the animal advocacy group carried out undercover investigations into four intensive poultry farms based in Norfolk and Suffolk that supply chicken to Morrisons supermarket. On all four farms they identified sick and injured birds living in filth despite being Red Tractor approved, a stamp that assures high welfare standards.

Investigators found badly injured birds unable to move on Red Tractor farms in East Anglia credit: Open Cages

Investigators found badly injured birds unable to move on Red Tractor farms in East Anglia credit: Open Cages

credit: Open Cages

credit: Open Cages

Another major criticism of the industry is its use of genetically designed chickens. Engineered to have larger breasts, eat less grain, and reach slaughter weight in just 35 days, they are some of the most successful consumer products in history. But Peter Stevenson from the animal rights charity Compassion in World Farming, believes that these 'frankenchickens' are the root cause of untold suffering.

"Growing twice as fast as they did 50 years ago means that often chickens suffer from heart disease, respiratory problems and painful leg disorders," explained Peter, who has campaigned to end factory farming for over 30 years.

A DEFRA funded study found that 27% of broilers had severe difficulty walking as their legs cannot support their rapidly expanding bodies. Whilst the UKRI found that almost a third of broilers develop heart and lung problems.

Being genetically identical and living in cramped and often stressed conditions also increases susceptibility to disease, Peter added. “It is a huge problem which the industry has known about for many years but done nothing about.”

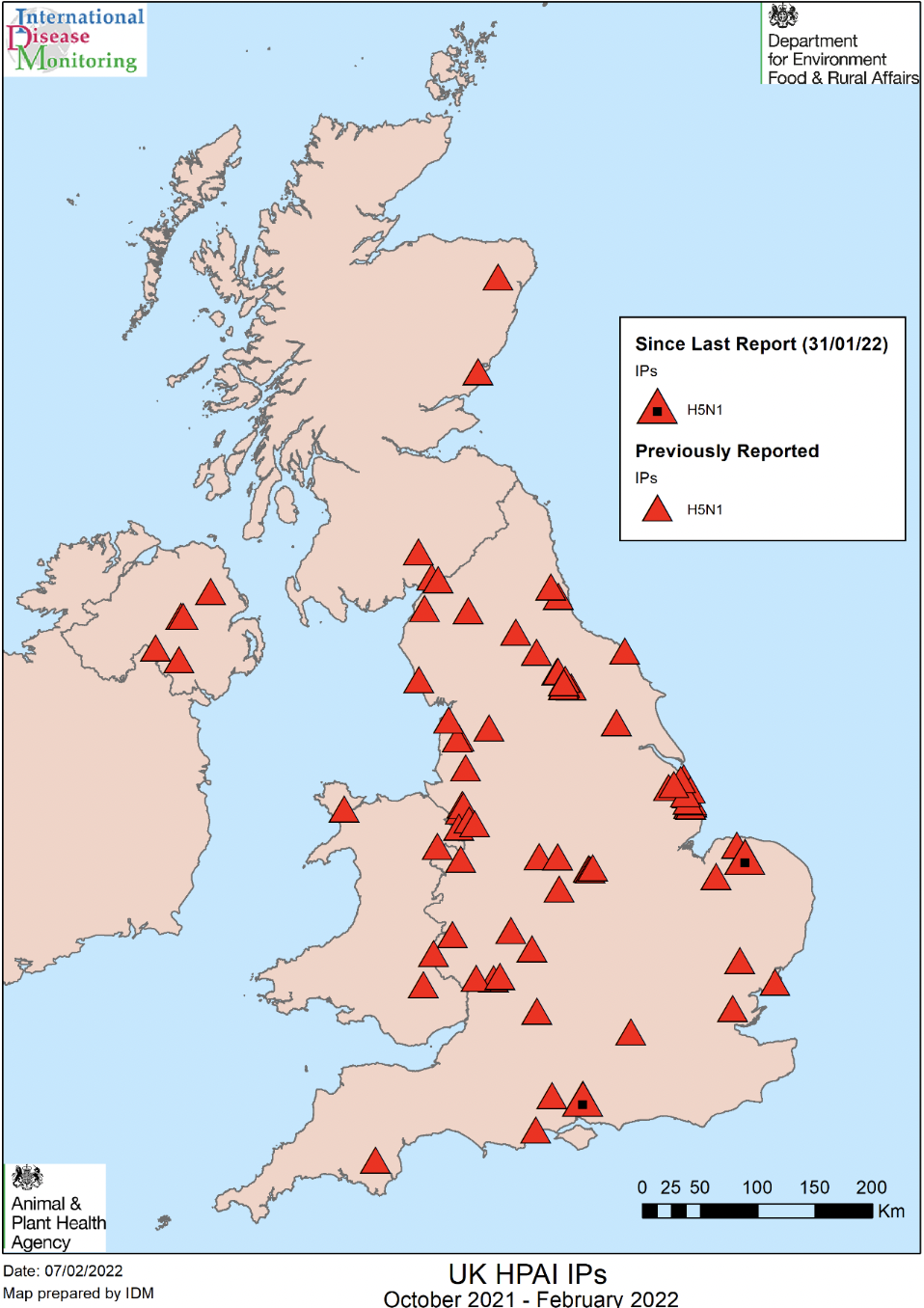

Last winter the UK suffered its worst outbreak of avian influenza on record, forcing all farmers to adopt strict biosecurity measures and keep all poultry indoors. Between September and February, an FOI request revealed that over 900,000 birds were culled as a result of outbreaks on British farms.

(image credit: Rawpixel)

Highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks in poultry and captive birds across the UK, October 2021 to February 2022. credit: APHA

Highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks in poultry and captive birds across the UK, October 2021 to February 2022. credit: APHA

DEFRA has also identified a new, highly pathogenic strain of bird flu affecting wild bird colonies. Normally, the virus passes through wild birds without harming them, but this year the RSPB has reported hundreds of geese, gulls and other seabirds getting sick and dying from bird flu across the UK.

image credit: Havardtl

Avian Influenza first came to international attention in 1996 but until recently it passed through wild birds without harming them. credit: Kieth Evans

Peter thinks it’s no coincidence that the 2009 Swine Flu outbreak originated in Mexico near to a major concentration of industrial pig farms. In fact, there is growing evidence linking potential future pandemics with these farming practices. In the peer reviewed journal, Science Advances, an article published earlier this year stated: “Large pig and poultry farms are where the genetic reassortment needed to source pandemic influenza strains may most likely occur.”

However not everyone is convinced that its indoor farms we should be worried about. Back in west-Norfolk, William Barber thinks people who keep chickens and other poultry as pets are exacerbating the spread of the virus. He pointed out that the first outbreak of avian influenza in the county last year, occurred in a backyard flock of 4 turkeys on a country estate.

“Never at any stage have people who keep poultry as pets bothered to keep their birds inside.

"They don’t think the rules apply to them.

“Professional poultry keepers are acutely aware of the risks and extremely careful,” he added.

If the virus were to reach William’s farm he said he would have to cull the entire stock and spend £60,000 on water alone just to deep clean the sheds.

image credit: woodley wonderworks

Today in Britain we are accustomed to paying just £3 for a whole chicken. But in the 1950’s, a chicken would have cost the equivalent of £11 in todays money. Whereas once a chicken was for special occasions, now it costs less than a pint of beer. Even the ‘chicken king’ himself Ranjit Singh Boparan, president of 2 Sisters Food Group, the UK’s largest poultry business has said chicken is now too cheap and called for a reset on pricing. It maybe the public agree. According to a recent YouGov poll, 78% of the British public are against factory farming for the sake of producing cheaper food.

In the immediate at least, it doesn't look like intensive farms producing cheap chicken are going away. But labour shortages post-Brexit and souring energy costs is putting the industry under mounting pressure. There is also a growing debate around the intensification of farming or whether we should shift to regenerative agriculture. Some argue that intensive farming produces greater quantities of food on less land, and helps to meet the rising demand for food. Yet others say we need to prioritise nature based solutions in agriculture in order to improve soil quality and sequester carbon.

Whatever happens, it seems demand for the nations favourite meat is set to rise. The OECD say more people than ever before are choosing chicken in high-income countries, since it's perceived as healthier and easier to prepare than beef or pork . More intensive farms are likely too. According to the British Poultry Council, the UK is only 65% self-sufficient in poultry meat production and still importing vast amounts from abroad.

For most of the British public however, intensive poultry farming rumbles along relatively unnoticed, somewhere out in the countryside. It is in the shops, armed with a shopping trolly and a bank card, when the nations feelings towards eating chicken are best expressed.

(image credit: Rawpixel)