The rise of ultrarunning

An investigation into why the endurance sport has become so popular.

Ultrarunning, an endurance sport where people run further than a marathon, is on the rise.

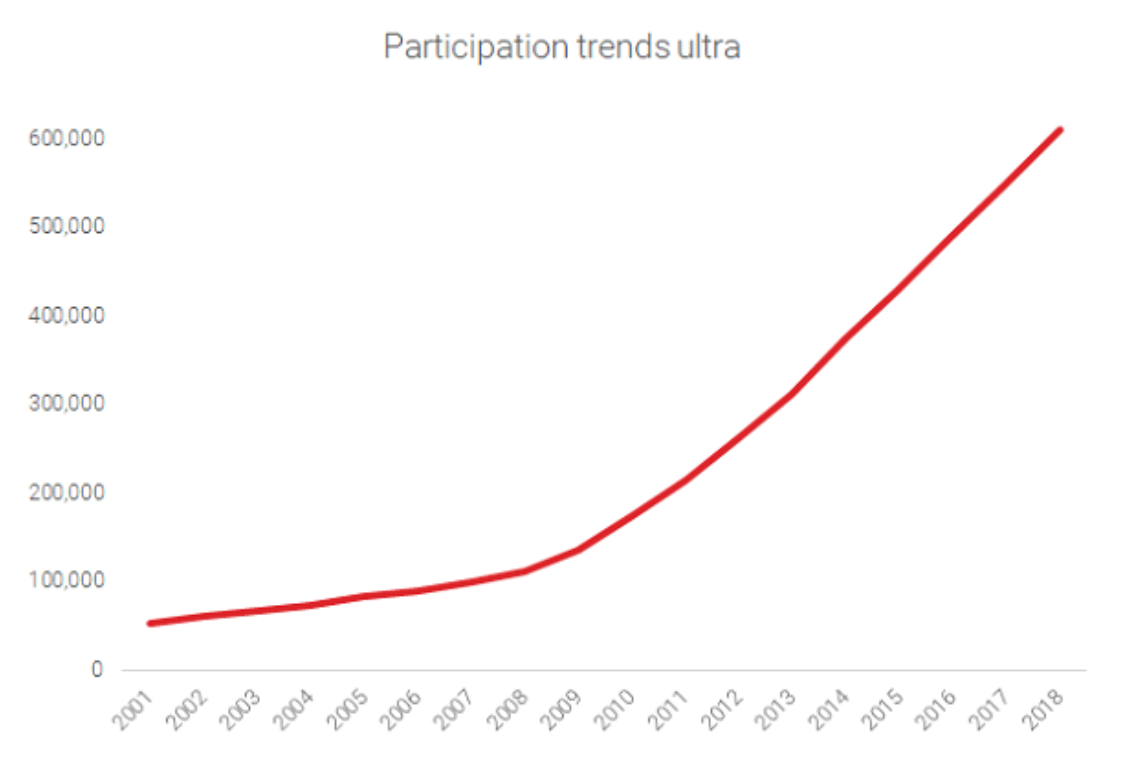

A report in May revealed that there has been a 345% increase in global participation of ultramarathons over the past decade.

It also showed a rise in the number of ultramarathon events springing up all over the UK, giving people more opportunity to get involved.

Distances typically start at 50km and there are different types of races, including road, trails, and loops which take place all over the world.

Races can last one day, a weekend or even a week such as the 250km Marathon des Sables which takes place across the Sahara.

Prices typically range from £50 for a one day event to a few thousand pounds for a multi-day event abroad.

The longest certified race in the world is the Sri Chinmoy Self-Transcendence 3100 mile (4988.9km) race in New York.

Runners have 52 days to complete the distance and are allowed to run from 6am to midnight each day along a 0.54 mile (883m) street.

What’s noticeable about the sport is that men and women compete together.

In 1992 Helene Diamantides and Martin Stone won the inaugural Dragon’s Back Race, covering 350km in five days, a result which arguably put female ultrarunners on the map.

In June 2021 the British ultrarunner Sabrina Verjee completed the Lake District’s 214 Wainwright peaks in less than six days, setting a new record and making her the fastest athlete, male or female, by more than six hours.

But why are more people getting involved in ultrarunning?

Credit: Steve Smith

Credit: Steve Smith

Credit: Steve Smith

Credit: Steve Smith

The pandemic has given people more time to train and for many this has meant an opportunity to challenge themselves to longer distances.

Restaurant manager Steve Smith, 33 and from Leicester, began ultrarunning in the first lockdown as he wanted to set himself a challenge and found running to be the most accessible option.

Steve has run 50km several times but has his sights set on the Lakeland 50 mile (80.4km), then plans to run 100km and eventually 100 miles (160.9km).

He said: “At the beginning of lockdown I wanted to push myself to see how far my body could take me and ultrarunning seemed the most attractive option.

“The best thing is the sense of achievement you get after completing a difficult run and seeing how much you can physically and mentally push yourself.”

Jack Mills, 29 and from Hampshire, took up ultrarunning at the end of 2020 and has found that the sport is not just about the personal challenge it provides but also about the inspiring community.

He said: “Ultrarunners are a very friendly, supportive bunch and there’s always someone who’s willing to help if you’re ever unsure which makes you feel part of something.

“I’ve connected with so many people from all over the world who inspire me to keep pushing.

“A question I ask myself a lot is ‘How far can I go?’ I don’t know the answer but there’s only one way to find out and it’s me against me, there’s no other competition.”

A key element of ultrarunning is the focus on participation and finishing, rather than the actual time a runner achieves.

For 25-year-old interior designer Harry Castle, ultrarunning provided the perfect challenge to force himself to get fit with an added bonus of no pressure of running a specific time.

Harry, who ran 100km from London to Brighton this year, commented: “It gave me a big sense of accomplishment as my aim was to just finish and it made all the hard work worth it.

“For a novice, the longer distance removes the pressure of finishing within a certain time, so you are able to actually relax and enjoy the race.”

Credit: Steve Smith

Credit: Steve Smith

For those who have been partaking in the sport for a while, the constant challenge and the journey of self-discovery can be an addiction.

Project manager Mark Atkinson, 40, has been running ultras for a decade and has even written two books about his ultrarunning journey.

Mark commented: “It’s a real journey and you discover a lot more about yourself and what is important in life.

“Ultrarunning feels a bit like it's for people who are having a midlife crisis but can’t afford a Porsche.”

For equine vet Naomi Mellor, who has been running ultramarathons since 2018, the sport provides mental freedom as well as satisfaction.

She explained: "Getting out for a long run is a huge stress-reliever for me, it's the time in which I can think things through and be inspired with ideas.

"There is also nothing more satisfying than persisting and succeeding in an endeavour that either yourself or others think you might not be capable of achieving."

Hugh Lovatt, 34, started running ultras in 2013 as a way to get fit and in 2019 ran the UTMB Mont Blanc going two days without sleeping.

He said: “When you actually cross the finish line you are so physically and emotionally tired that there is sense of overwhelming relief.

“The realisation only kicks a few days later when you have rested and then you start planning your next challenge.

“Ultrarunning is its own unique sport and community, it is much more than just physical capability, but about preparation, the ability to survive extreme conditions in the mountains, to problem solve, to navigate, it just brings in so many different elements.”

Hugh was used to seeing about seven people on the start line but now events are often sold out.

He has his eyes set on the Tor des Géants, a 330km endurance trail race in Italy, which scares him the most.

Background photo credit: Hugh Lovatt

Credit: Camino Ultra

Credit: Camino Ultra

“People enjoy ultras as you push yourself to a better existence in your daily life because of what you have experienced”

Credit: Camino Ultra

Credit: Camino Ultra

As runners have increased so have the opportunities to participate in an ultrarunning events, with the focus on simply just finishing proving to be an advantage to race organisers navigating COVID-19 restrictions.

David Bone, 49 and cofounder of events company Camino Ultra, commented: “In ultras staggered starts are widely accepted.

"It’s much more about the fact that you finished rather than your time which is healthy and takes the pressure off, whereas if you are running a marathon people are much more focussed on your time.”

The company, which was set up by David and Darren Strachan in January 2020, hosts ultras in and around London and wants to make the ultramarathon world more accessible.

David explained: “Our objective is to create a supportive and welcoming entry point into this new world.

“We want people to be out in nature, enjoy themselves, and take time to look around and get good air quality all the while reducing the footprint of how far people have to travel to access these events."

Camino Ultra's next event is a 50km race in Epping Forest in October and 76 runners have already signed up.

Sam Heward and Jamie Sparks started Ultra X in 2018 as a passion project with an aim to create the first multi-stage ultramarathon series and to make multi-day racing accessible to all.

The company was forced to adapt its plans due to COVID-19 and organised its first virtual ultra event.

Sam explained: “It was actually so much fun, it gave people something to be motivated about and there is nothing more accessible than a basically free race you can do from your front door.

"It is all part of our vision to create an ultramarathon brand which has a greater diversity of people involved, including younger people and more women.

"A big part of that is educating people to help them realise that they can run an ultramarathon if they want to and that’s what we set out to do.”

Ultra X hosts events all round the world including in Jordan, Sri Lanka and Wales.

By doing so the company hopes to make ultramarathons accessible for different markets and to encourage local people to participate in the races.

Upcoming events include a 250km five day race in Jordan in October which is sold out and a similar race in Mexico in November.

The growing popularity of ultrarunning has also led to the emergence of the first 'premium ultra'.

The Highland Kings, a four day 120 mile (193km) race in Scotland, will take place in April next year and includes butlers, Michelin-star chefs and luxury accommodation all for a fee of £15,499.

There are 40 places available and the event is already a quarter full.

Member of the organising team Mark Hayward said: “It is absolutely something new for ultrarunning as it brings the sport and luxury together.

“It is going to be fantastic journey, from the seven months of training leading up to the four days of the actual event.

“We are offering something different and the Highland Kings is breaking new ground.”

There are questions around accessibility and representation in ultrarunning.

Whilst the costs of ultrarunning events can be a barrier, runners often need to be able to read a map, survive in extreme conditions and know what to do if they get into trouble.

Moreover, the typical ultrarunner tends to be white, male and middle aged.

Black Trail Runners launched in July 2020 and is a charity which campaigns to break down barriers within ultrarunning and to increase inclusion, participation and representation of black people in trail running.

In 2020, the group collected ethnicity data for nearly 800 UK trail race entrants for 2021 and discovered that less than 1% of runners were black.

Sabrina Pace-Humphreys, one of Black Trail Runners’ founders, explained: “Often when we have been on the start line of races we are the only people of colour, we are the only people that look like us, so we wanted to address that.

"0.7% of race entrants are black and it’s not because black people don’t want to trail run, it’s because there are major barriers within trail running which are access, skills, and representation.

"Our ultimate aim for Black Trail Runners is for there not to be a Black Trail Runners because it's not an issue, because we have addressed the representation and we have increased diversity."

The charity is currently hosting The Black Trail Runners 4.5 Challenge where people complete 4.5 hours of any activity on Strava before the end of August to get the Black Trail Runners 4.5 Challenge badge, and then make a donation of £4.50 or more.

According to the 2011 UK census, black people make up 4.5% of the UK population.

The money raised will be donated to charities such as Trailfam, an East London group which aims to get more young people on the trails.

“You only need to go to a trail race to see that there is a diversity problem in trail running”

However ultrarunning is not without its' dangers.

In May this year 21 runners died when high winds and freezing rain struck a 100km race in Gansu province in China.

The country has since suspended all ultramarathon and long-distance races and an official government investigation report stated that the emergency and safety measures were not in line with standards and that the rescue service was underprepared.

Despite this tragedy, the endurance sport of ultrarunning looks like it is only set to grow and in the years to come it is likely there will be many more impressive and gruelling races to choose from.

See you on the trails.