The secret battle for the internet's past

Websites are dying, and they're dying at an increasingly rapid rate.

Pew research recently released an alarming set of statistics, which included an estimate that 38% of webpages which existed in 2013 are inaccessible as of 2023.

Half of Wikipedia pages contained at least one reference to a page which no longer exists.

Unique online information doesn't seem to fare much better on social media either.

Even before Musk’s takeover (which has surely exacerbated the trend), the survey found nearly one-in-five tweets (as they were known) became invisible to the public after being up for just a few months.

Accounts being suspended, deleted or made private accounted for the lion’s share of this trend (60%) while in the rest of cases the account remained active and the individual tweet was removed.

But what does this trend mean? Why should we care?

From the perspective of an individual internet user, a dead website usually translates into that all-too-familiar and frustrating encounter: ‘404 Error’, ‘Oops… This page cannot be found.’

The disappointing experience usually tails off there. So, one might ask why we should even ask or care about what happens when a specific website 'goes down'. Surely one can just move on and find the information elsewhere?

If one chooses to see a webpage merely as a pop-up on a screen, the matter can seem very trivial. But this, of course is not the case.

Webpages are a medium to transfer information. In short, they are media, just like books, documents, songs, videos.

Imagine attempting to find a book or a song (especially one you previously encountered, or knew to have existed before) but then found it had simply 'vanished' or 'could not be accessed'.

When understood as pieces of media, the seriousness of website death becomes apparent.

Despite efficiency and versatility, qualities which guaranteed their takeover of analogue formats, online media are actually uniquely susceptible to extinction if not maintained.

Physical documents can waste away and degrade, effort being required to preserve them, especially more ancient artefacts.

But websites, no matter how new or old, are always just one step away from becoming lost in the void. Construct a site without making a backup of the data; if it goes offline, the information will most likely be gone forever.

The required upkeep of online media, the constant updating of software and security of every individual domain, has meant the threat of data becoming unrecoverable or 'lost media' is now very real.

When online media goes offline, without any attempt to preserve or revive, the content contained within becomes what is known as 'lost media'.

Writer and journalist JD Shadel, who has written extensively on the subject of archiving 'lost media', stressed that the 'loss' is not just a matter of losing the digitised content itself but about the 'loss' of what that content recorded.

They said: "We lose the evidence of how we thought, communicated, and organized ourselves during pivotal historical moments."

According to Shadel, the popularity and ubiquity of online media being concentrated in so few platforms has led to a particularly vulnerable situation.

"Who owns and controls these spaces often have considerable power with the delete button", they added.

"Without preserved digital culture, future researchers won't understand how social movements formed, or how everyday people experienced major events.

"We're essentially creating massive gaps in the historical record of the early 21st century."

This sentiment was echoed by Nichole Lamerichs, a senior lecturer at HU University of Applied Sciences Utrecht, whose research focuses on play, fandom and digital culture.

'Lost media', Lamerichs said, can not only be understood as a degradation in public knowledge but also as a conduit for intense emotions linked to memory and meaning in the internet age.

She said: "The 'loss' of media is not only recorded but felt; apart from a loss of data, there is an irrevocable part of our memories of feelings that become unplaceable."

"The 'loss' of media is not only recorded but felt; apart from a loss of data, there is an irrevocable part of our memories of feelings that become unplaceable."

Digital archiving is a practice whereby digital media (webpages, videos, graphics, games etc.) are recorded and stored, overwhelmingly in other digital databases.

The preservation of online (or once online) media is therefore peculiar in that the digitised content being preserved is done so via other digitised means.

Where these archives are open and publicly available on the internet (as a great number of them are) the archived material almost seems to have been magically revived.

The open-source ethic which motivates much digital archiving in the modern era is inspired precisely by this sentiment.

By combining the rigour of traditional archiving techniques with the accessibility of the internet, digital archivists are able to construct a uniquely democratic model of media preservation.

The following are just a few examples of such major archival projects.

Flashpoint Archive

At one time it was thought the demise of Adobe Flash (outpaced by HTML 5, CSS and JavaScript) would lead to the extinction of millions of digital media, including countless online games of the early internet which relied on the early software.

However, through the concerted effort of grassroots organisations like the Flashpoint archive, alongside collaborations with legacy archival institutions (such as The Strong Museum), Flash-based media is having a small renaissance.

More than 150,000 flash games can now be readily downloaded from the Flashpoint downloadable archive, available for recreation and researching purposes.

End of Term Web Archive

The stated mission of the End of Term (EoT) Archive is to preserve the public, online activity of all three branches of the US Federal Government for posterity.

At the conclusion of every administration since 2008, volunteers at the EoT Archive have made 'harvests' of successive Governments' online presence, ensuring their survival after each transition of power.

So extensive is the archive that it has been given its own collection in index of the the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine.

The WayBack Machine is one of the most crucial tools of the amateur and expert digital archivist.

Approaching 1 trillion interactive 1 trillion interactive snapshots snapshots of webpages, the WayBack Machine is a virtual time-machine. Select a website, browse the available dates, and you may effectively see the past.

Decades old websites, even those which are long dead, have been revived.

A monumental example of the WayBack Machine's power was witnessed in the case of Apple Daily, a former Chinese- and English-language newspaper which was at the forefront of the pro-democracy protests which gripped Hong Kong in the late 2010s and early 2020s.

Set in motion by the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to the People's Republic of China, by the late 2010s the city-state's major institutions were coming under increasing pressure to surrender their independence and autonomy in line with the mainland Communist Party's 'One China' policy.

The independent press, with Apple Daily as its vanguard, was one of the last major institutions in Hong Kong to voice dissent.

Just before it was shut down for trumped-up breaches of the new 'National Security' law in 2021, scores of anonymous internet users, coders and archivists scrambled to preserve the organisation's online material.

Pages are interactive, graphics slide and navigation by internal links is preserved, all despite the paper having been forcibly removed from existence years ago.

The WayBack Machine showed it was not just an archiving tool but could also provide a major bulwark against authoritarianism and powerful government censorship.

Archiving and activism blended into one.

Apple Daily's online pages, a key historical source on the demise of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, have been saved from the void.

As mentioned by Lothian-MClean, gal-dem, was a pioneering digital publication in the UK, an outgrowth of the feminist, gender and racial justice movements of the 2010s.

While it might have become ash she said 'frozen in amber', the Internet Archive maintains an extensive catalogue of the magazine, preserving the site while the British Library's digital library recovers from an extensive cyber attack.

Preservation attempts involve the participation of countless anonymous internet users, uploading snapshots and interacting with the archival infrastructure which the Internet Archive and others provide.

Of course, this decentralised aspect of digital archiving has lent itself to independence and autonomy, channelling users' individual specialisation(s) and personal attachments.

These conditions have in turn motivated users to curate their own archival spaces, esoteric collections of or homages to digital media which would otherwise be forgotten.

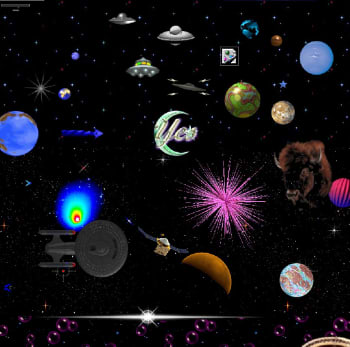

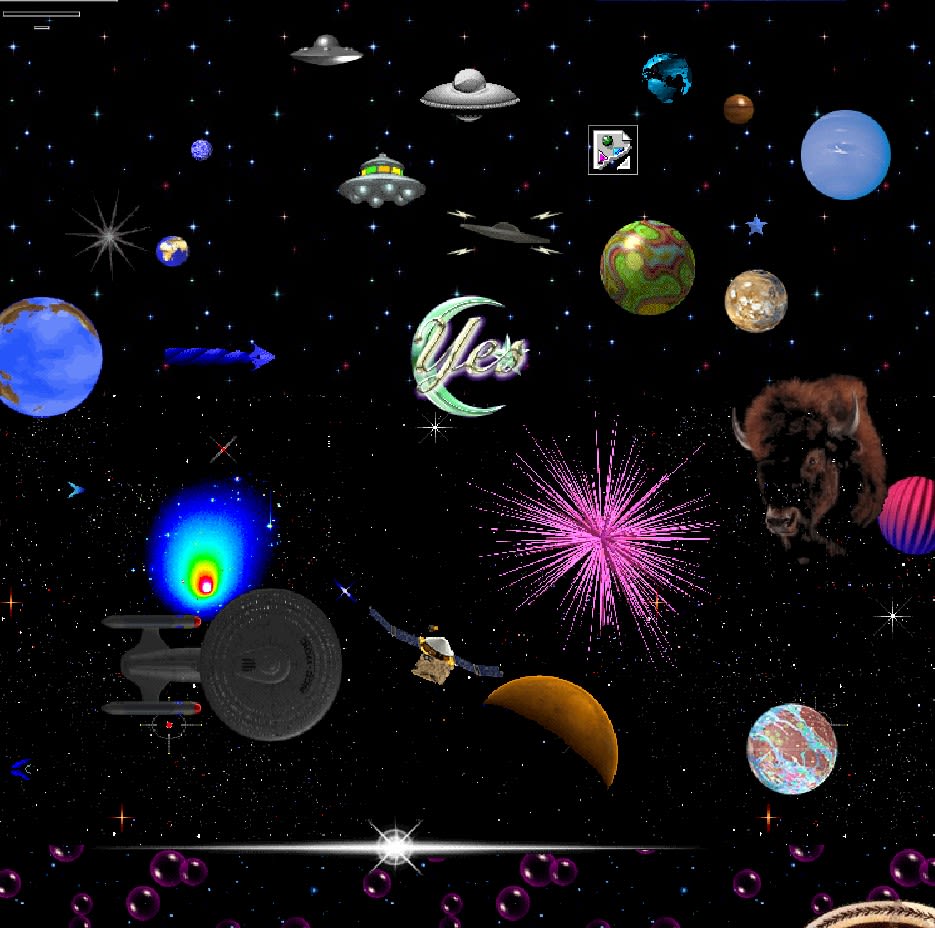

Cameron's World is just one instance of this kind of individual-nostalgic creative form of preservation.

Resplendently busy, Gifs and loud colours populate a tribute to Geocities webpages, the site hearkening back to a time before embedded media became seamless.

Another project reviving access to endangered media comes from Riley Walz's IMG_0001, a site which utilises an obsolete feature of iPhones that used to allow users to upload videos straight to Youtube from their camera roll (which appear titled as IMG_xxxx).

These short videos often have zero views, some of the more popular might have a few dozen.

The site has preserved time capsules of lives from the early 2010s: celebrations, memories, insignificant, casual or provoking events.

Despite the triviality of individual videos themselves, the site itself has succeeded in creatively asking users to tap into the notion of lost and endangered media.

The individual effort of these creators has humanised digital archiving, elevating the practice into own medium, its own artform, spurring future interest and participation.

You don't need to be a digital archivist to use the Wayback Machine to fact-check politicians or corporations who stealth-edit their public statements."

In this vein, Shadel emphasised the independence of modern digital archivists is a vital and unique strength.

They said: "The most encouraging trend is how preservation efforts are becoming more distributed and collaborative.

"Projects like the End of Term Website show institutions working together rather than trying to preserve everything in isolation.

"I'm also heartened by how preservation tools are becoming more accessible to ordinary people.

"You don't need to be a digital archivist to use the Wayback Machine to fact-check politicians or corporations who stealth-edit their public statements."

Despite the open-source, collaborative ethic of much digital archiving, huge barriers have been posed to the model.

Most immediately, the Internet Archive was recently threatened with hundred-million dollar lawsuits from the publishing and music industries, seeking assurances against what they claim is plagiarism of their content.

The evolution of online content towards short-form, disappearing formats could pose a major threat to archival efforts.

These highly time-sensitive media have increasingly become the mainstream way digitised content is communicated, especially digitised news.

"What we lose with ephemeral formats on major platforms concern me if they can't be preserved in an accessible way," Shadel added.

"Instagram stories, Tiktok videos, Discord conversations - the platforms that feel most culturally significant right now are also arguably the most resistant to preservation."

Whether archival techniques can adapt to the speed of Web 2.0 content has become perhaps the most pressing challenge for future digital media preservation.

As the volume and variety of online media accelerates exponentially, there is a danger that the opposing rate of media obsolescence, matching this rapid pace, becomes insurmountable.

As the future of digital media expands, so too does its past.

This is the paradoxical, uphill battle which digital archivists have been dealt, and the stakes could not be higher: our collective, online memories are depending on them.