The Veterans War

For many veterans, the fighting doesn't stop once you return to "civvy street."

A sudden loud noise reminiscent of gunfire, the scent of burning debris or a crowded street become portals, transporting veterans back to the frontline where they relive moments of intense fear and distress.

The invisible battle that lingers within takes the form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

For those who suffer, it seems the battleground has merely shifted from external to internal, and the war within the mind can be just as formidable.

Recognising that our veterans carry the weight of their experiences long after the uniform is retired is essential in fostering a compassionate and supportive environment that allows veterans to feel understood.

Charities are vital in providing health and welfare services to those who have served in the armed forces to help them transition back into society.

Their stories may no longer be in the headlines, but for many veterans, that does not mean they are not still at war.

Living with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): "the unwelcome companion that refuses to be left on the battlefront."

Karl Wade, 35, from Northamptonshire, joined the army with the Grenadier Guards in 2008 when he was 20 years old.

After his second tour in Afghanistan, Karl was sent on 'sick at home' leave in 2014 and was then discharged for PTSD and secondary-degree depression in 2016.

For Karl, his PTSD began after he got back from his 2012 Afghanistan tour.

“When I was going through the start of the illness, I didn’t know what was going on or how I was feeling," he said.

“I knew about PTSD but it was something that I thought wouldn't happen to me.

Karl (right) at a garden party at Buckingham Palace 2012 (Credit: Karl Wade)

Karl (right) at a garden party at Buckingham Palace 2012 (Credit: Karl Wade)

“It was like I was standing still in the middle of a motorway and everything was just rushing past real quick and I didn’t know how to get across.

“I couldn’t cope, I couldn’t deal with it, I couldn’t function.

“But obviously in the military, it’s a very man’s world so you don’t talk to anybody about your problems and you just hope that they will pass as you keep trying to get through each day and survive.

“But when I came back from the 2012 tour, I started feeling and acting different.

“I was scared of my actions.

“The day I left when I was diagnosed with PTSD in 2014 I never went back.

"It was a big blow as my career stopped instantly.

“Being diagnosed with PTSD was really hard to deal with.

“It was really hard to digest that wow there is actually something wrong with me that is out of my control."

But for Karl 'it all went really wrong' in 2018, just before his daughter’s first birthday.

“The wheels just fell off.

“My relationship ended, I closed my locksmith business down as I wasn’t well enough to go to work and I became homeless.

“I had nothing and nowhere to go.”

Alex Harrison, 36 from Lincolnshire, also served in the Grenadier Guards, which he joined when he was just 16 years old.

One early morning out on the ground, Alex was shot at point blank range in the head by a Taliban fighter waiting in an open door. The first round went through his helmet, then his temple, bounced off of the bottom of his eye socket and came out of his eye, causing instant blindness and ending his career on the ground.

“You know the only abroad holiday I’d ever gone on was to Italy," he said.

"To then go to Iraq and see the Middle East for all its glory, no pun intended, it was pretty eye-opening as an 18-year-old lad.”

Alex at his passing in parade in Harrogate, 2003 (Credit: Alex Harrison)

Alex at his passing in parade in Harrogate, 2003 (Credit: Alex Harrison)

For Alex, his severe complicated PTSD (which he wasn’t diagnosed with until 2018) started imminently after he got out of the army in 2009 and his mental health took a nose dive.

“In 2007, I lost three major things that were important to me: my eye, coinciding with my army career, one of my best friends who was killed in a car crash and my driving licence.

“It was a brutal year.

“I was keen to be 22 years a soldier and to have it all whipped away in a snap six years after joining was pretty heartbreaking.

Alex as an army cadet, 2000 (Credit: Alex Harrison)

Alex as an army cadet, 2000 (Credit: Alex Harrison)

“There were quite a few years where I was silently struggling.

“Struggling to get my head around what had happened and civilian life.

“I hit alcohol like a freight train to try and help me cope.”

But in 2013, Alex hit a really low point with his PTSD.

“I was struggling to hold jobs down and finances had changed at home.

“I was a wrecking ball.

“My Mrs turned to me and she said you need to go get help or I’m leaving with the kids.

“This cannot go on.

“You're destroying yourself and everything around you and I’m certainly not going to be letting the kids be a part of it.”

In response to his wife Sarah’s ultimatum, Alex sought help at the Archway Centre, Lincoln.

“The first therapist I ever had said to me ‘I can’t make it go away but I can make it better for you to live with'.

“That was a bitter pill to swallow.

“It almost sent me into more of a downward spiral because I realised I’ve got to live like this for the rest of my life.”

For both Karl and Alex, it wasn't their former employer, the Ministry of Defence, but charities who saved them.

When life hit an all-time low for Karl, the Colonel’s Fund stepped in and pointed him in the right direction.

Karl said: “Family and stuff in terms of as a support network wasn’t great.

“If it wasn’t for the Colonel’s Fund, I would have had nothing.

“They are the family I never knew I had.

“They remind you that you are still part of the brotherhood.”

Matt Elmer, the regimental casualty officer for the Grenadier Guards Colonel’s Fund charity, took Karl down to Veteran’s Aid, a homeless charity, in London where he lived in a hostel and saw a doctor at Harley Street who put Karl on the highest dosage (375mg) of medication for PTSD and deemed him unfit to ever work again.

The Colonel’s Fund helped Karl furnish a new flat so he could start afresh and helped him during times of overwhelming anxiety throughout a family court case and an ongoing battle for compensation against the Ministry of Defence.

However, the Colonel’s Fund Yukon 700, an ambitious, self-sufficient seven-day canoeing expedition through the Yukon waterways of Canada, has had the greatest impact on Karl.

“There is more of a spark in me since coming back from the Yukon.

“Before the Yukon, I would drop off my daughter at school and get back into bed for the rest of the day as I waited to go pick her up.

“Now I’m getting up, going out and about and I’m going to the gym.

“Doing that challenge has shown me that yes, you can be poorly, but you are still able to push yourself.”

Karl (fifth left) at the Yukon 7000, Canada (Credit: Karl Wade)

Karl (fifth left) at the Yukon 7000, Canada (Credit: Karl Wade)

Seven years after suffering quietly, Alex approached his former regiment, the Grenadier Guards, for help in 2016.

Alex was 'one of the ones who had slipped through the net' and there had been no one to catch him and support him through his return to civilian life.

The Colonels Fund insisted he would be 'squared away' and helped finance part of his landscaping company, which he has now had to close down due to his body taking its toll from his injuries.

It wasn't until Alex 'got into a bit of drama with the police and ended up in court' that he was put onto a programme with Walking with the Wounded, where the Colonel's Fund paid for 12 sessions with a psychologist, who diagnosed him with severe, complicated PTSD.

Nine years after Alex had left the army.

Alex emphasised that it was down to his rock and his wife Sarah and charities Blesma, Walking with the Wounded and the Colonel's Fund, that he is still here with us today.

Alex doing stand-up as part of Poppy Scotland's "Recovery through Comedy" (Credit: Alex Harrison)

Alex doing stand-up as part of Poppy Scotland's "Recovery through Comedy" (Credit: Alex Harrison)

“I don’t think its right that we should be reliant on charities.

“It’s about time something substantial was put in place.

“The number of suicides is not going down.

“You can send people to war but then when they come home, you’ve got to look after them.

Alex now (Credit: Alex Harrison)

Alex now (Credit: Alex Harrison)

“It's not a very nice thing to do to go and fight. It’s about time the government look after us as we are the ones they lean on to do their dirty work.”

According to new figures from the Ministry of Defence, one in eight UK forces personnel sought help with their mental health last year, a figure which has risen steadily over the past decade.

Support for these armed service personnel and veteran charities are facing challenges

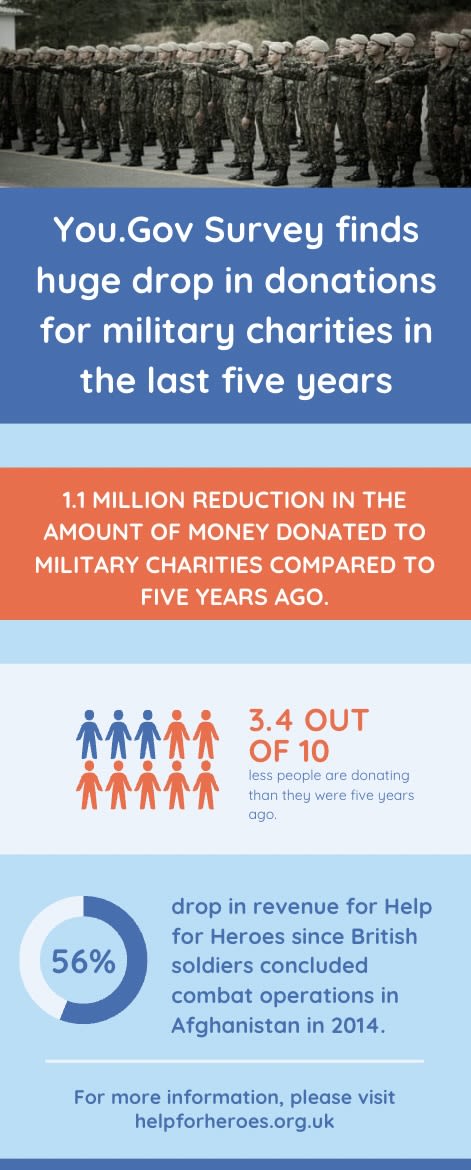

New research shows that one million fewer Brits are donating to military charities compared to five years ago.

A YouGov study conducted on behalf of the military charity Help for Heroes revealed a 1.1. million reduction in the amount of money donated to these organisations over the previous five years.

An estimated 3.2 million Brits donated to these types of charities in 2017. In 2022, that number dropped to 2.1 million.

Help for Heroes, which has seen its own revenue drop by 56% since British soldiers concluded combat operations in Afghanistan in 2014, has referred to the loss in support as 'a worrying trend because the daily struggles of our Armed Forces community are no less challenging, nor have they gone away.'

Robert Marsh, Combat Stress’ director of fundraising and veteran who served in Bosnia in the late 90s, said: “The cost-of-living crisis is far more threatening for us than Covid-19 was.

“We are reliant on our strategic partners and their benevolent funds as well as our donors.

“Some have had to withdraw their funding because they’re worried about their own coffers’, some have had to reduce it and some will not uplift it by inflation.

"We also need to see some constant and committed funding from the NHS rather than the current fluctuations.

"Scotland and England give us a grant towards helping treat veterans, but Wales and Northern Ireland give us nothing.

“Our costs have increased and so we are having to spend our reserves, which is fine as that is what they are there for.

“But we can’t keep on spending our reserves as they will run out and the worry would be well, if we are not around, who would pick up these people?

“We need more consistent statutory funding over a longer period of time so that we can plan ahead, give more hand-to-mouth services and make sure the covenant is upheld, which states that your military service should not disadvantage you.

“If you develop a mental health issue as a result of your service life, then you should be looked after properly.”

CEO of First Light Trust Dorinda Wolfe Murray felt that the £10 million funding package to support veterans' mental health services that was announced in the Autumn Statement was all well and good but added: "Even so, as a grassroots organisation, we are not going be getting the funds to consistently give the support that creates real bonds.

"It's messy. It's hard work. It's not a tick box exercise. The understanding of grassroots and community are needed to deal with the complexities of PTSD which doesn’t make for top-down funding."

To find out more ...

Listen to Talking with the wounded for more inspirational stories from veterans

Ben Stephens invites the listener into his conversations with the wounded about the moments that changed their lives.

"Headbutting Bullets" features Alex Harrison.