Trouble in Paradise

An ignored blight of offshore tax abuse is plaguing Britain and its overseas dependencies

Small, windswept and mostly sunny: Britain's global network of imperial leftovers are not a bad place for a holiday.

Appearances of tropical bliss, however, hide their role in empowering global tax abuse, in turn fuelling political corruption and societal inequalities.

A decade on from the Panama Papers, the leak of the Pandora Papers and the scandal surrounding Sir Geoffrey Cox MP's representation of the British Virgin Islands in a corruption inquiry has returned focus to the murky world of offshore tax havens.

Far more pronounced than many realise is the importance of Britain in this whole affair.

The sun may have set on the British Empire, but tax abuse continues to run riot in Britain's remaining overseas dependencies

The sun may have set on the British Empire, but tax abuse continues to run riot in Britain's remaining overseas dependencies

Just a few months ago, Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party government looked unassailable. The so-called vaccine bounce propelled him miles ahead of the opposition in the polls, prompting talk of a 10-year spell as Prime Minister.

Now, he is clinging onto his job after a bruising series of scandals that started with allegations of sleaze against Tory MPs.

November’s botched attempt to save ex-minister Owen Paterson from a 30-day suspension by rewriting the rulebook on parliamentary standards may be the most notorious of these.

But it was Sir Geoffrey Cox’s use of his House of Commons office for private legal work that started a trickle of public discontent that has since become a torrent.

The MP for Torridge and West Devon – who made almost £900,000 in 2020 through private work as a barrister – was pictured in a virtual meeting representing the government of the British Virgin Islands from his parliamentary office.

The Labour Party reported this to the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards, arguing that it was a breach of standards as MPs cannot use their offices for “personal or financial benefit”, but no investigation was deemed necessary.

The significance of the Cox affair lies not only in the questions it raises about MPs’ second jobs, but in its implications for Britain’s relationship with its last vestiges of Empire.

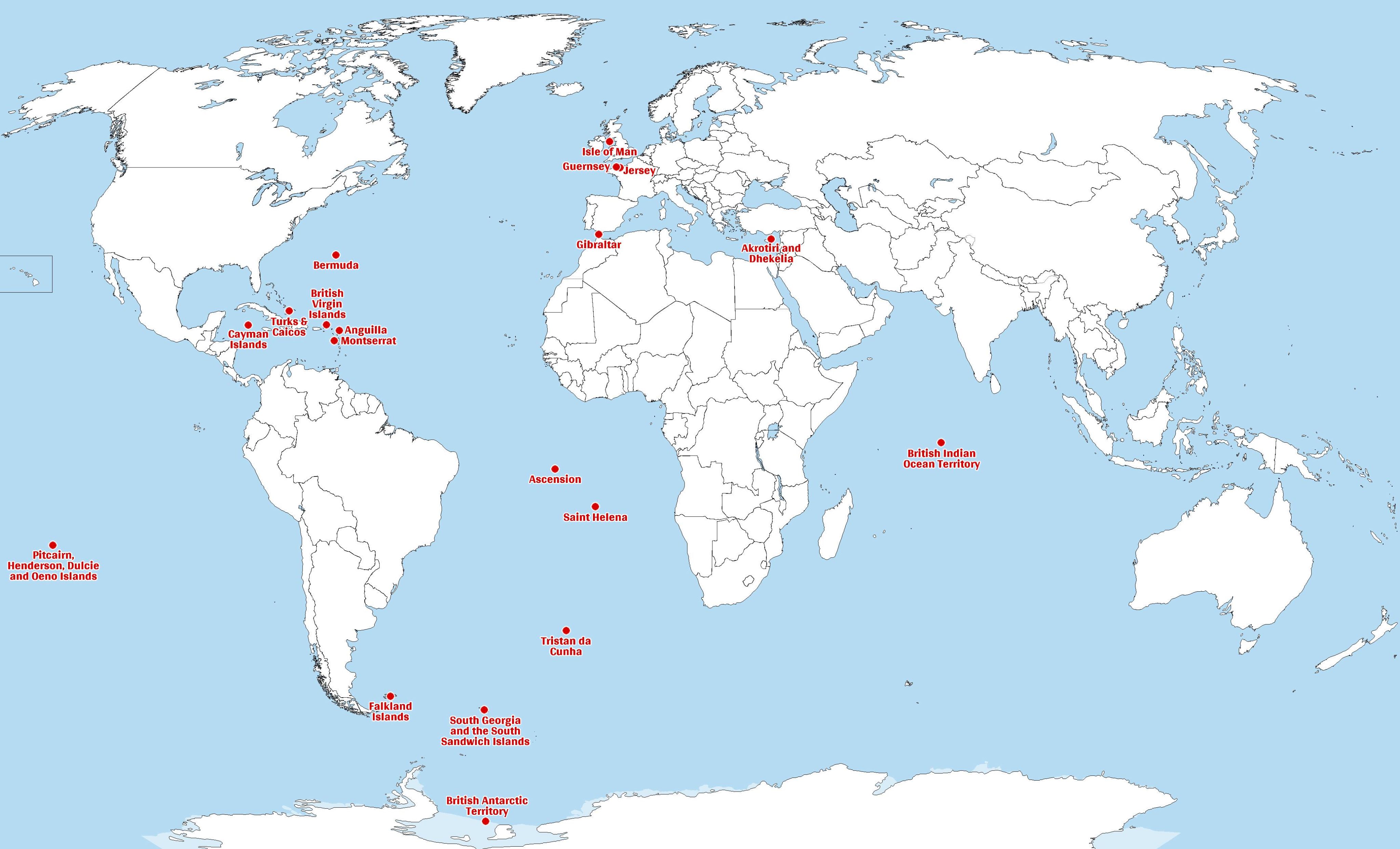

Britain's 18 Overseas Territories and dependencies

Britain's 18 Overseas Territories and dependencies

Cox, after all, was acting as counsel in a corruption inquiry against the British Virgin Islands, a Caribbean tax haven and one of the few remaining slices of the world possessed by the UK.

Britain has 14 overseas territories dotted across the oceans, from the Virgin Islands in the Caribbean and two armed forces bases on Cyprus, to the Pitcairn Islands in the Pacific and a slice of Antarctica. It also has three crown dependencies, Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man.

Most of these 17 territories are self-governing, with the UK government responsible only for defence and foreign affairs. This administrative flexibility has permitted divergence from the UK’s own tax regime, with low corporate rates rolled out and owner anonymity institutionalised.

Attracted by the resultant opportunities for secrecy and profit retention, multinational companies have flooded in.

The Tax Justice Network, an anti-tax avoidance advocacy group, estimates that eight of Britain’s territories – the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, Gibraltar, Turks and Caicos, and Anguilla – are responsible for 28% of global corporate tax abuse, despite accounting for just 0.0005% of the world’s surface and 0.0065% of its population.

In 2018, it was revealed that 237 global economic crime cases worth a total of £250bn had been enabled by 1,107 companies based in British Overseas Territories, 90% of which were in the British Virgin Islands – the government of which employed Sir Geoffrey Cox as counsel in a corruption enquiry.

For Dr Alex Cobham, the Tax Justice Network’s chief executive, the co-existence of financial crime and political corruption is no coincidence in small island states whose economies are heavily dependent on international finance.

“You get to a position where you’re so dependent on the financial sector and particular individual and corporate actors within it that you can no longer make policy decisions without making sure it works for them,” he said.

“It strips out a lot of the democratic accountability of government because you become accountable to the financial sector, rather than directly to your electorate. And that’s why so many of the UK territories, over recent decades, have fallen into such deep problems of governance.”

The effects of tax abuse in Britain’s overseas territories and dependence are not limited to these places alone.

When revenues and profits are ferried away from Britain, this country not only loses out on the proceeds of taxation that would have stemmed from it, but also the economic growth potentially spurred by their reinvestment and the positive impact of this on regional and demographic inequalities.

These effects are exacerbated by the UK’s own tax regime, one which is dominated by taxes on spending rather than wealth.

As a result, the proportion of a person’s income that is taken by tax is higher for those on lower incomes, limiting their ability to save, invest or spend on self-improvement relative to those who earn more.

As the old adage goes, it takes money to make money.

“That means worse lives for people at the bottom, but actually also worse outcomes for everyone,” explained Dr Cobham. “Inequality at the kind of level that we have in the UK results in worse social outcomes for everyone.

"We have not just worse education and lower economic growth, but also worse health outcomes across the board, including mental health, because inequality is bad for us, this isn't how we're supposed to live.”

Furthermore, these inequalities are more likely to effect women and people from ethnic minorities, as Dr Cobham explained in the below clip:

What, then, can be said about a solution?

Tax abuse is an issue that carries immense political weight. It strikes right at the heart of the sense of fairness that animates so many political debates in Britain, from migration and the quality of healthcare to lockdown restrictions and compulsory vaccination.

Those on both sides of all these debates believe they possess the ultimate trump card: that the position they support is the fairest.

Ultimately, it is the unfairness of those who choose to not pay the tax they could that motivates the public ire that Jimmy Carr, Gary Barlow and David Beckham have all faced for their part in tax dodging schemes.

An October 2021 poll by Survation found that 81% of the public believe that corporate tax avoidance is "morally wrong even if legal".

But at present, no major political party has a comprehensive policy proposal for eradicating tax loopholes or using negotiation or legislative powers to change these territories’ tax regimes from above.

Another issue entirely is how – if the political will is found – to do so in a sustainable manner that limits the impact of significant change on those who live there.

“The broader question for the UK is how it deals with this set of dependent territories around the world, all of them largely feeding money into the City of London,” said Dr Cobham. “If you were to switch that off tomorrow, it would be a massive economic shock for the UK.

“Ultimately, you'd be in a better position because you'd end up with a more balanced and fairer economy, but you don't want that kind of sharp shock.

“And similarly, you don't want to do that to any of those dependent territories where there are real people entirely dependent on those economic structures,” Dr Cobham continued.

“How do you find a way through that? How do you help the normal people in the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands and Jersey, as well as in the UK, to find alternative economic paths that are much less damaging for the rest of the world?”

That, indeed, is the million dollar question.