Turning Up the Volume

How the London music scene is fighting for survival

Grassroots music in London, and across the UK, has had yet another tough year, but there are signs that this vital industry might be getting back on track.

Although the figures continue to tell a bleak story, with venue closures still on the rise and profit margins tighter than ever, many London venues and artists are finding ways to not to just survive, but thrive.

Add this to the prospect of a Premier-League-style arrangement whereby big, arena venues donate a portion of profits to the grassroots, the future is looking brighter than it has for some years.

This not to say, by any means, that the challenges facing the industry have gone away, the cost of living crisis continues to push many venues to, and over, the edge.

However, venues are managing to find new and innovative ways to stay afloat in what are certainly choppy waters.

An industry in crisis

Since the pandemic, numbers of Grassroots Music Venues (GMVs) across the UK has dropped every year.

"The enthusiasm for live music is still there, but what you can charge for tickets or beer simply isn't enough to pay all the additional costs that have been hoisted upon live music."

The MusicVenueTrust is a charity which works to support the grassroots music scene.

It publishes annual data on the state of the music industry, including the number of GMVs that have closed.

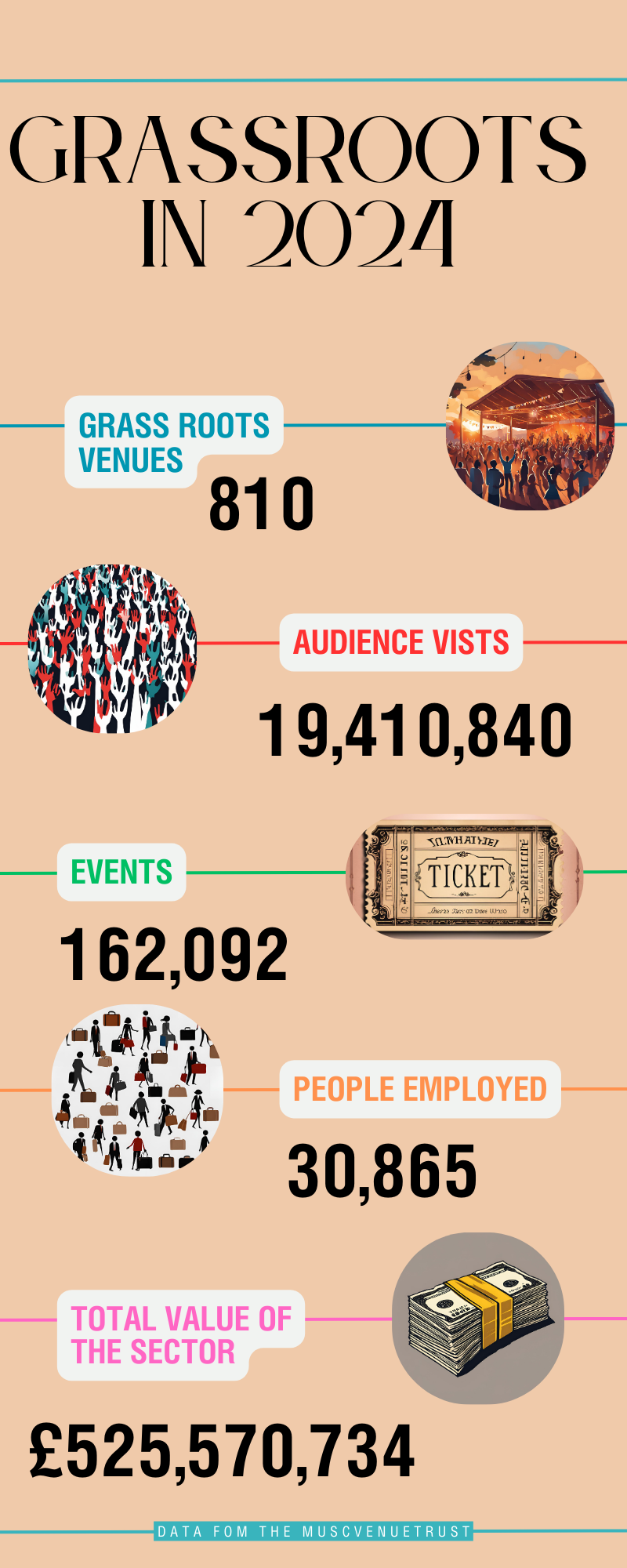

In 2024 there were a total of 810 GMVs, down from 835 the previous year and 960 in 2022.

Founder and CEO, Mark Davyd, found that the number one reason for GMV closures in 2024 was the spiralling costs associated with live music.

From hiring staff to take tickets on the door, to paying engineers to rig lighting and sound systems, to increased security due to licensing rules, doing business as a live venue is a significant investment.

What has been crippling for so many venues is the skyrocketing cost of energy and rent - challenges which have affected all pubs, bars and clubs in recent years.

Mark pointed to the 30% increase in rent and over 400% increase in energy that hit GMVs after the pandemic.

He said: "Coming out of the pandemic, they're being hit by external forces.

"Based on the data, there hasn't been a change in the appetite for live music, it's the costs that have gone through the roof."

One type of consumer behaviour Mark did identify as having changed was the consumption of alcohol.

He said: "People do not like to be seen on their social media drunk, so they're curtailing their drinking for that reason.

"People are also living healthier lifestyles, so the spend-per-head once someone is in the venue is significantly down."

However, 2024 has seen significantly fewer closures than previous years, indicating that the trend may be losing momentum.

Additionally, the numbers employed by the industry is now higher than it was in 2022, and the total value of the sector has remained consistent since the pandemic, even increasing by 5% last year.

This goes to show that in many venues, the music is far from having died.

The Half Moon

The Half Moon in Putney has remained a steadfast institution of the London grassroots scene since the 1960s and is trying innovative ways to keep music fans coming back.

This has meant putting on several acts per night, all week long, cheap tickets, free booze and slick social media to court an increasingly unpredictable consumer base.

A taste of New Music Nights at the Half Moon credit: @halfmoonputney

A taste of New Music Nights at the Half Moon credit: @halfmoonputney

New music manager at the Half Moon, Phil Atkinson, has been putting on an eclectic show of up and coming acts every Monday night since 2017.

Phil said: “You can’t just open the doors to a pub anymore and expect people to come in.

“You have to be giving people a reason to come out, whether that be food, comedy or in our case, live music.

“So, what we’ve done is really ramp it up.”

The Half Moon often puts on as many as four or five acts in a single evening and upwards of 20 per week.

Phil said: “We’re sort of saturating it, and I’ve found that for us that’s really worked.

“You’re not reliant on one audience that likes one band or one genre to come in.”

On a New Music Night, where audiences can experience a variety of genres from sometimes very different artists, the Half Moon not only charges the persuasive ticket price of just £2.50 but even throws in a free beer to boot.

But the Half Moon is in the privileged position of being able to consistently book high quality acts and bank on having a full house.

Given its rich history and recognisable name, the Half Moon is able to trade on its brand identity in a way that smaller, newer venues simply cannot.

Phil said: “ I look like I'm dead good at my job, but I'm literally just putting on these bands who've got in touch with me and they're absolutely brilliant.

“We’ve got people flying over from Los Angeles to play a Monday night selling for £2.50.

“If you're just starting out, it'd be difficult.

“I'm under no illusions that people are emailing me thinking I want to speak to Phil.

“They don't know who I am, but they know who the Half Moon is.”

For those venues which didn’t, like the Half Moon, play host to pop royalty such as the likes of The Rolling Stones and Ed Sheeran, packing the house with revellers on a weekday night can prove a taller order.

Kevin Jones, founder of the High Tide Festival and co-owner of Eel Pie Records in Twickenham, talks about the importance of grassroots music and how it's becoming a harder lifestyle to live

For a lot of people, this is what gives them the reason to live, the reason to enjoy their lives. We're particularly good at music in this country but it has been a little bit forgotten and left to wither.

Kevin Jones speaking at his shop Eel Pie Records in Twickenham. For subtitles, select 'subtitles/closed captions'.

A solution...?

In an effort to save venues that are on the brink, campaigners in the industry, notably the MusicVenueTrust, have been pushing for a Premier-League-style levy system for live music.

This would see the biggest players and profit makers, such as arena venues, superstar acts and their promoters, contribute a portion of sales to sustain the grassroots, which they rely on for the next generation of talent.

Mark, from the MusicVenueTrust, has been calling for such a system for years, a campaign which has seen the government release an official statement in November urging the industry to make this change voluntarily.

Mark said: "I have no doubt at all it will become a widespread practice.

"The only question now is will the biggest companies in the world voluntarily take part in order to support the development of new talent, which they currently don't invest in at anywhere near the level they need to."

Mark highlighted the responsibility that big companies have to the grassroots scene.

He said: "What happens is the local venues, acts and promoters invest millions into developing grassroots talent.

"If the artist's career goes well, that's when a big international company will come in and be the one to start making money.

"But the big company doesn't come in until significant money has already been put in at a grassroots level."

A levy of this kind, which is already used in France, would take £1 per ticket from arena gigs to create a centralised fund that venues, artists and promoters can apply for.

Phil, at the Half Moon, said: "I think it's a brilliant idea.

"The Premier League does it, because that's how they can get the players coming through from the grassroots

"Without the pitches you play on as a kid, you're not going to get the superstars that make you a fortune in the future.

"If they want the Taylor Swifts and the Oasis' of the future, they need to support the grassroots."

Kevin, from Eel Pie Records, said: "It's got to be a good idea, and it's got to help so I'm 100% behind it."

However, Kevin did express some doubt that the scheme would be enough, by itself, to reverse the trend of the last few years.

"It's critical that live music is where it starts and live music is where it grows from."

As the industry negotiates with both big business and the government, others are taking it upon themselves to kick-start a trend of donating to struggling venues.

Matty Whelan, 25, is a part-time musician who is planning on donating £1 from every ticket he sells in an upcoming gig (at the Half Moon) to the MusicVenueTrust.

Matty knew of the proposed levy on the biggest money makers, but realised he had yet to see a similar initiative at a grassroots level.

Matty said: "I felt that if there was something I could do at my level to support the spaces I’m playing in then I wanted to do that.

"I think there's a real movement building, it's a really exciting thing to be a part of and I want to play my part."

Matty has first-hand experience trying to make his way as a gigging artist in London, which for many is harder than ever.

He said: "The amount of venues that have closed, in the fallout of the pandemic, means there's less and less spaces for up and coming artists to cut their teeth.

" I don't feel that artists, including myself, really pin that on the venues themselves because we all recognise the kind of climate we're all trying to operate within."

Of course, not all gigging artists have the financial scope to be so generous and community minded.

Matty is able to do so because music makes up only part of his income.

He said that the idea of making a living by doing music full-time, especially at a grassroots level, is currently out of reach for most aspiring musicians.

It seems that to have any chance of success in the current climate there was one factor artists and venues neglected at their peril: social media.

Gone are the days of 'what's on in London' lists published in Time Out magazine that served as universal, night-out bibles.

Nowadays, the best way to reach the punters is through the often fickle algorithms of Instagram and TikTok.

As Matty said: "I would much rather focus on the music, but I do engage with social media, I have to engage with it.

"You have to market yourself aggressively."

Matty was keen to stress, however, that even the slickest of socials cannot make up for a lack of boots-on-the-ground stage time in front of real people.

He said: " It's critical that live music is where it starts and live music is where it grows from.

"Those are the best gigs and those are the best artists."

If we want to keep enjoying world-class music in our capital, and across our country, we're going to have to fight for it.