What's Wrong with Wet Wipes?

Wet wipes are a staple in most households.

They can be used to clean, remove make-up, and are especially useful when it comes to children.

They are frequently used in health-care settings to sanitise as they are easily disposed of.

Eleven billion wet wipes are used in the UK each year.

And crucially, up to 90% of them contain plastic.

Wet wipes are a single use plastic, and there are increasing calls for environmental legislature to treat them like other single use plastics.

The main problem for our environment and households is when wet wipes are flushed down the toilet.

They combine with oil grease and other items to form fatbergs which block our drains and sewers.

Sewer blockages can cause flooding, have significant maintenance costs and crucially cause environmental damage to watercourses.

When our sewers are blocked and they overflow, wet wipes often end up in our rivers and on our beaches.

Not only does this affect the wildlife when the small beads of plastic end up in their stomachs, but the build up of millions of wipes can actually change the shape of the river.

The impact is phenomenal, and only recently being registered and analysed.

"It's like flushing a small plastic bag down the toilet"

When people flush wet wipes, they end up in our sewers, and form fatbergs.

The plastic in wet wipes make them sturdy enough to form these huge lumps, and cause tens of thousands of blockages each year.

Utility companies spend millions clearing these wet wipe fatbergs. Thames Water cleared 1,500km of sewer this year using shovels, hand picks and high-pressure washers.

If you look at a pack of wipes, they often have a small symbol of a toilet with a cross through it, signalling they should not be flushed down the toilet.

Some toilet wipes have a 'Fine to Flush' label, which technically means they break down in water. But the reality of that label is being questioned.

The main issue is that the labelling on packaging is unclear, and sometimes misleading.

The test to obtain the 'fine to flush' label costs money and is not mandatory, so companies often opt for other tests that show their wet wipes are instead biodegradable.

But just because wet wipes are biodegradable, doesn't meant they're okay to flush.

And just because they're fine to flush, doesn't mean they don't have plastic in them.

Companies like Thames Water are also developing technology to identify build-ups of plastic waste before they become a significant problem, but the technology hasn't kept pace with the rate in which people are improperly disposing of wipes.

Duncan Gibbons, a spokesperson from Thames Water, said: "We know many busy people and families love the ease and convenience of these products, but most are made from plastic and don't break down in the water like toilet paper does. It's like flushing a small plastic bag down the loo.

"If you're using wet wipes, even if they say they're 'flushable', please pop them in the bin instead of the toilet. 'Flushable' wipes still contain plastic, and although they might disappear down the U-bend, they can still cause blockages.

"The three Ps is the best rule to remember when it comes to what's flushable: pee, poo and toilet paper."

Clump of wet wipes being lifted from a sewer in Mogdan, near Twickenham. Credit: Thames Water

Clump of wet wipes being lifted from a sewer in Mogdan, near Twickenham.

A Thames Water worker, Vince, shovelling a broken down fatberg. Credit: Thames Water

A Thames Water worker, Vince, shovelling a broken down fatberg. Credit: Thames Water

Impact on our rivers

Everything that is in the sewer when it overflows ends up in our watercourses, including wet wipes.

This is becoming abundantly clear in the River Thames.

Environmental charity Thames21 is one of the only organisations that works to clear the Thames of litter.

But their volunteers not only pick up litter and attempt to make the river a pleasant place to be, they also record data on what sort of litter they collect.

Volunteers started noticing wet wipes on the Thames foreshore over a decade ago, and by 2014 Thames21 had set up their river watch program, where trained volunteers started counting and recording the number of wet wipes they collected.

Chief Executive of Thames21 Debbie Leach said: "We've had thousands of volunteers out there on the Thames foreshore, it's amazing.

"It's not a glamourous task. But they're out there rain or shine counting these things and removing them from the river and still we see it growing year on year. Something needs to be done about this.

"The first thing is never ever flush a wet wipe. It's going to be one of those things like remembering to put on your seatbelt when you get into a car. We all do it now without even thinking."

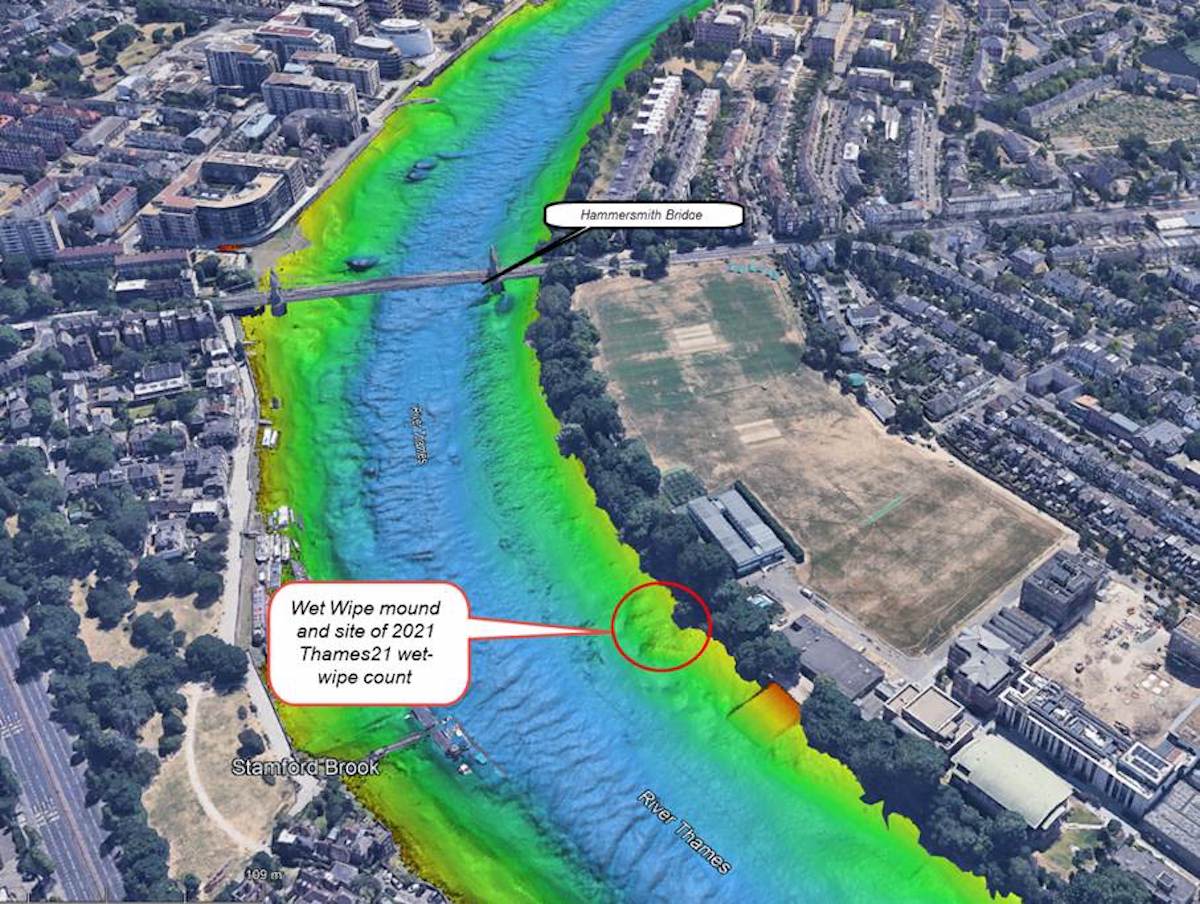

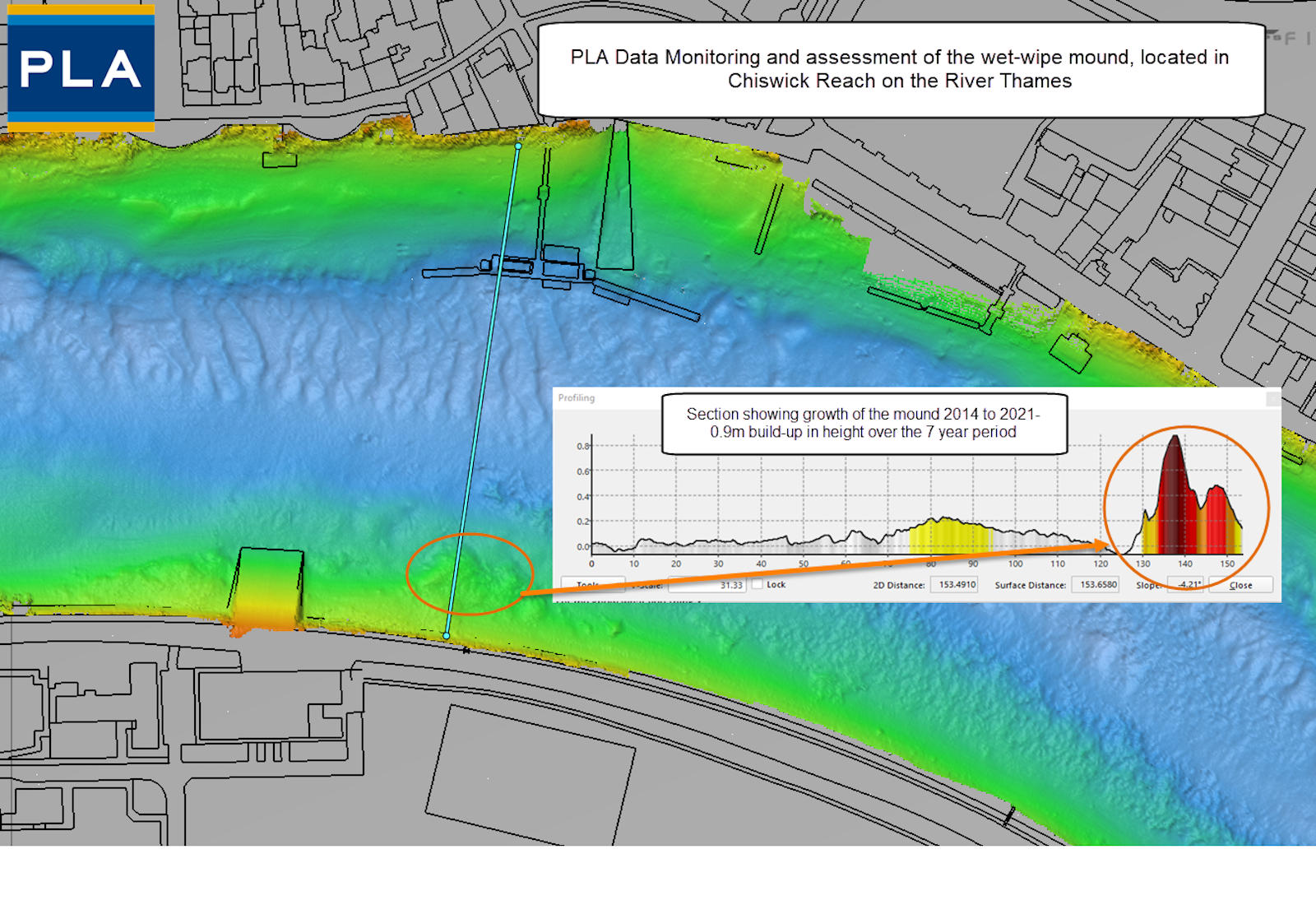

The corners of the river are natural collection points for the wet wipes, which bind together with silt and twigs to form huge mounds in the river bed.

These can actually change the shape of the river and affect its flow, and further than that, birds and fish peck and nibble at the wet wipe mounds, which has caused micro plastic beads to be found in their stomachs.

Currently at a site under Hammersmith Bridge, for example, there is a collection of wet wipes that is roughly 1000 square metres. That's about four tennis courts.

On the surface, volunteers counted 50-100 wet wipes per square meter. Given the depth of the mound, there is thought to be around one million wet wipes forming the collection.

The mound is still growing despite volunteer efforts to clean it up, and this is just one of the wet wipe sites.

It is hard for volunteers who count these wet wipes to be accurate about how many remain in the huge lumps given their depth into the river itself.

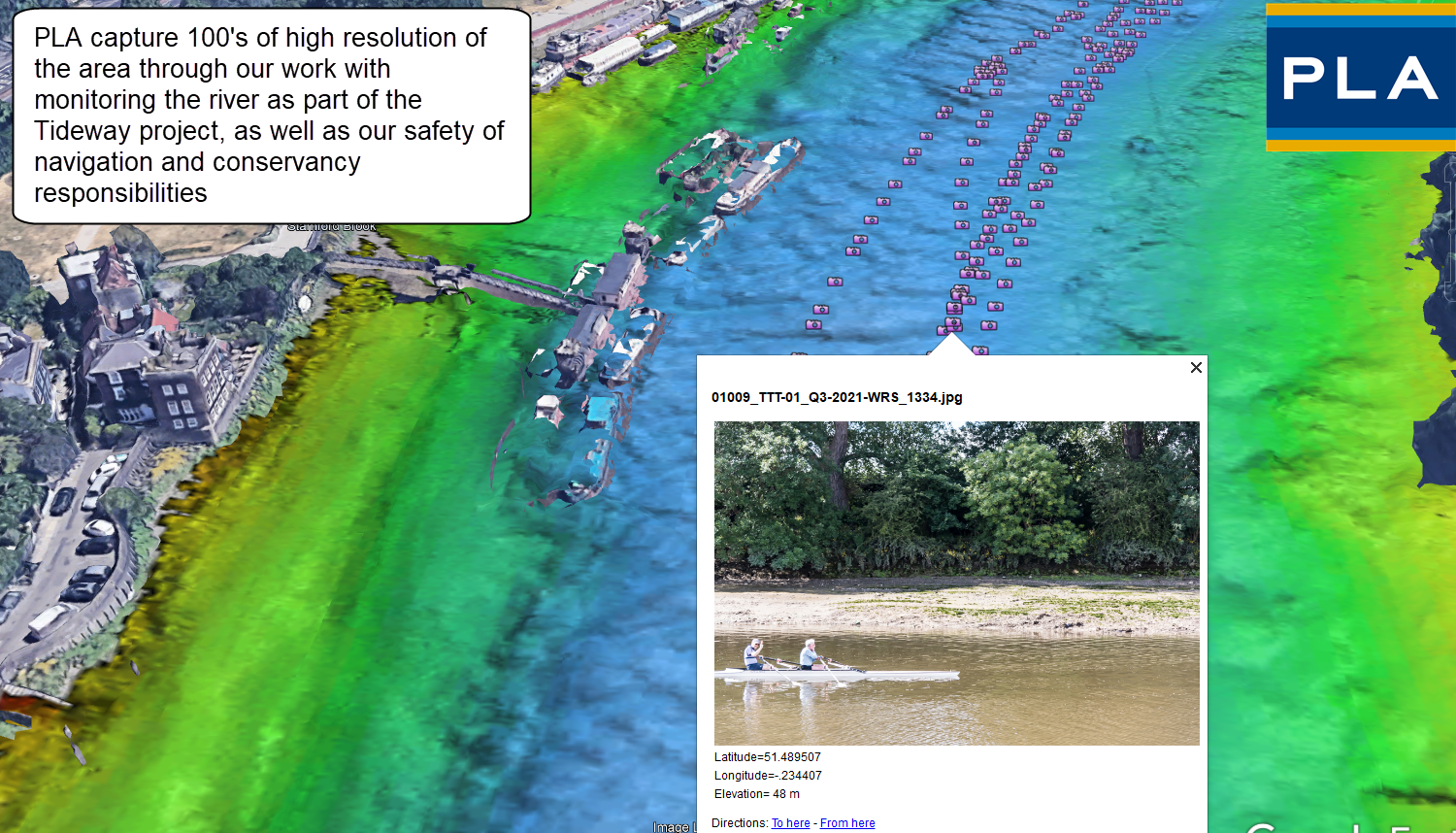

Construction company Tideway, who are building a large sewer under the Thames to prevent overspill, have been working with Thames21 to start to capture and monitor the collection of wipes at the Hammersmith Bridge site.

The technology is able to register the changing size of the lump, and also monitors the affect the lump of wipes is having to the level of the river and how it changes the shape of the river bed itself.

They share the information with the Port of London Authority (PLA) and the Environment Agency, which are significant steps in aiding Thames21's work.

John Dillon-Leetch, a hydrographer at the PLA said: "We're just helping Thames21 and Tideway to map that data and have the background to see what's happening. We will continue to monitor it going forward and look at what's changing.

"The way to stop it growing is to stop the wet wipes going into the river, which is what Tideway (the Tideway Tunnel) is about, to capture that overspill when it rains. About 80-90% of that overspill will be captured, including the wet wipes that are in the sewers. But the main thing is, bin it don't flush it.

Credit: Port of London Authority

Credit: Port of London Authority

Credit: Port of London Authority

Credit: Port of London Authority

Credit: Port of London Authority

Credit: Port of London Authority

I spoke to Debbie Leach, Chief Executive of Thames21 about their work.

I spoke to Debbie Leach, Chief Executive of Thames21 about their work.

Port of London (PLA) Hydrographer explained to MP for Putney Fleur Anderson about the way in which the PLA monitor wet wipe collection sites.

Port of London (PLA) Hydrographer explained to MP for Putney Fleur Anderson about the way in which the PLA monitor wet wipe collection sites.

Chief executive of Thames21 Debbie Leach joining volunteers in clearing up wet wipes from the Thames. Credit: Thames21

Chief executive of Thames21 Debbie Leach joining volunteers in clearing up wet wipes from the Thames. Credit: Thames21

A combined effort is being forged as plastic wet wipes are increasingly being registered as a significant problem, and this includes legislative changes.

On 2nd November, Putney MP Fleur Anderson proposed a bill to prohibit the sale and manufacture of wet wipes containing plastic to help tackle the huge problem.

This would remove a crucial element in the wet wipes that causes them to have such an impact on the sewers and environment, and eliminate them as a single use plastic.

It's the plastic in the wet wipes that is one of the main components that make them sturdy enough to form these fat bergs and mounds.

While proposing the bill, Anderson outlined the scale of the problem and praised certain retailers, such as Sainsbury's, for offering their own plastic-free options.

Referencing her own use of wet wipes as a mother of four, Anderson confirmed this wasn't a ban on wet wipes, just plastic ones.

Anderson praised the Environment Bill, which has now been passed, on its steps to reduce single-use plastics, but emphasised that wet wipes are a significant single-use plastic.

The bill was in the wake of COP26, and Anderson posed banning this plastic as another step toward preserving the environment: "If our global house is on fire, we will need many buckets of water to put it out, and here is one of them."

The bill is due for its second reading in February, but shortly after the bill was proposed, the government launched a public consultation on single use plastic.

This included plans to investigate how to limit other polluting products such as wet wipes, polystyrene cups and plastic cutlery.

I spoke to Anderson on Millbank Pier in the wake of this new public consultation.

I interviewed Fleur Anderson, who proposed the private members bill which hopes to ban the sale and manufacture of wet wipes that contain plastic.

I interviewed Fleur Anderson, who proposed the private members bill which hopes to ban the sale and manufacture of wet wipes that contain plastic.

Anderson alluded to the time pressure, and how it took such a long time for the environmental bill to be passed.

This echoes some environmental groups who have expressed frustration at the pace that these changes are happening at.

But in the mean time, the message remains the same. Don't flush wet wipes.

Debbie Leach (Thames21), John Dillon-Leetch (PLA) showing support for Fleur Anderson's wet wipe bill.

Debbie Leach (Thames21), John Dillon-Leetch (PLA) showing support for Fleur Anderson's wet wipe bill.