Wow! Have you lost weight?

Why weight-loss compliments are problematic

"Wow, have you lost weight?"

"You look great! What's your secret? Atkins?"

"I love your new look. You can really tell you've lost a bit."

"You look so much better now you've lost weight."

Complimenting someone for losing weight is problematic.

You have no idea how they got there.

They might have a chronic illness or an eating disorder.

They might have lost weight through stress or anxiety or heartbreak.

Their appetite might have dwindled because they're miserable.

You praising their weight-loss is implicitly praising those circumstances.

You don't know what their relationship with their body is like.

They might be struggling to love themselves or trying to fade into the background.

They might not appreciate you bringing attention to their weight, shape or appearance.

You don't know what your comment will do.

It might put pressure on them to keep off the weight, regardless of the consequences.

It might prompt them to view their past self as inferior or disgusting.

It might encourage them to see their new, potentially problematic behaviours or circumstances as admirable or worthwhile.

It might send them into a spiral of over-analysis, wondering what you really thought and how they really looked.

This article explores weight-loss and body image from three points of view.

Elaina has cystic fibrosis.

Martha is on the clinical team at the UK's leading eating disorder charity and has personally battled with bulimia.

I recently lost a sixth of my body weight under mysterious circumstances.

We all agree that weight-loss compliments should be avoided.

Scroll down to find out why.

Elaina Mowle

Cystic Fibrosis

Elaina has cystic fibrosis (CF), a genetic condition where her internal organs get coated in thick, sticky mucus that disrupts her digestion and leaves her susceptible to chest infections.

She discusses her experiences with chronic illness on social media, including how it affects her weight and body image.

The stereotypical CF sufferer is very slim. Regular chest infections generally cause weight-loss, partly because coughing and treatments get in the way of eating.

Even during periods of relative wellness, medicines have to be spaced out from certain foods – something Elaina described as a ‘jigsaw’ – and people with CF have to consume more food to get the same energy as someone without the disease.

Being underweight can mean more chest infections, so people with CF are instructed to eat a lot, to snack, and to choose high-calorie foods as much as possible to stay healthy.

Growing up, Elaina had no problem maintaining a healthy weight, which she found confusing.

"Here I was," she said, “having this disease which was supposedly supposed to make me really skinny and really tiny, and I never was that.”

Yet as a teenager, Elaina did become tiny. In 2018 she ended up in intensive care with a severe chest infection which caused her to lose a lot of weight.

She told me how upsetting it was to look in the mirror and see herself like that, “like a little skeleton”.

In this state, she felt she finally met the beauty standard. She noted she received more male attention and people complimented her on her physical transformation.

She said: “I looked more ‘healthy’ when the reality behind the curtain was that I was coughing so much that I was sick, I had to be on oxygen, I thought I was going to die. It was not pretty.

“I should never have reached that point. If I had had a healthy body that would have never happened.”

Elaina worked hard to put on weight, and with the help of steroids, she succeeded.

However, as she reached a healthier weight, she found it difficult to get rid of the image of her size 8 body.

She was split between longing for this apparently ‘better’ body and remembering how ill and unhappy she had been at that weight.

She said: “My physical health was the best that it had ever been but mentally I was really struggling, because every time I looked in the mirror, I didn’t like myself.”

Since then, Elaina has gained more weight, largely due to stints of steroids that increased her appetite to the point she said it sometimes felt as if she had lost control of her body. This came with better lung-health.

She said: “I’m bigger than I expected to be having CF. I’m bigger than anyone else I’ve ever seen with CF on social media.

“But I’m so healthy at the moment, physically speaking, from a lung point of view, and that is really important.”

On Instagram and YouTube, Elaina engages with the body positivity movement and chronic illness community.

She said: “Everyone can relate to the body image conversation and not liking yourself very much and feeling pressure from what you should or shouldn’t look like.

“But it’s so dangerous for it to be celebrated in something like CF because you don’t want to end up small and skinny and tiny.

“It could literally be life or death.”

Scroll down to watch the full interview.

Martha Williams

Beat Eating Disorders UK

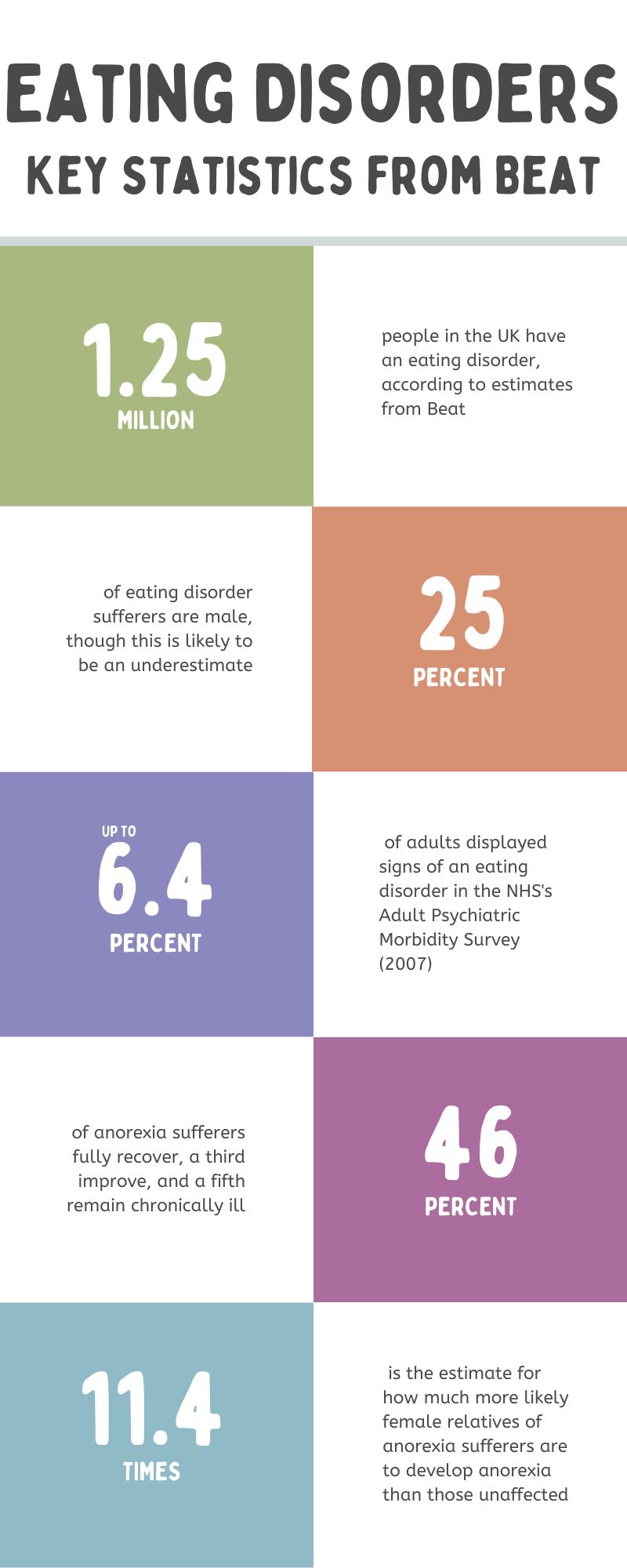

Martha is on the clinical team at Beat Eating Disorders, the UK’s leading eating disorders charity.

She’s lived in south west London her whole life, she’s training to be a psychotherapist, and she has lived experience with bulimia.

I began our interview by asking what eating disorders actually are.

Martha explained that they are diverse, complex mental health disorders.

‘Comorbidities’, or co-existing conditions, like anxiety or depression, often lie at the root of an eating disorder.

Martha said: “Eating disorders are actually not so much about the food or the weight or the shape. It’s those difficult emotions that lie beneath.

“What I like to do is think of an iceberg. At the top, the bit above the water, you might have restriction, bingeing, vomiting, over-exercising.

“And then underneath you’ve got all the really difficult feelings, the bit that you can’t see under the water, like perfectionism, low self-esteem, anxiety, depression – all of those sorts of things.”

I asked her how weight correlates with eating disorders.

Martha emphasised the importance of not judging the severity of someone’s eating disorder on their appearance.

I was interested to hear how weight-based comments and compliments might affect someone with an eating disorder.

Martha was diagnosed with bulimia in her teens.

“At the time,” she said, “I think I really struggled with that diagnosis because I wasn’t significantly underweight and I didn’t think that I was ill enough to be bulimic.”

She described the moment when she finally spoke to someone about it.

“I felt so shameful for so long about lots of the different things that I did, like the bingeing and purging and all of that, so for someone to listen to that and say, it’s okay, you’re unwell, you’ve got bulimia, was quite a relief and quite a shock at the same time.”

Martha never saw herself as fitting into the stereotype of someone with an eating disorder.

She said: “I wasn’t deathly underweight and everyone that I knew that had had an eating disorder had suffered from anorexia and it was very, very clear and very visible that they were unwell.

“That’s what I struggled with, because I didn’t necessarily look really underweight or really unwell.

“But that obviously had no impact on how I was feeling. I was in a really dark place.”

It's impossible to tell someone's relationship with their body from how they look. It's safer not to comment.

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, you can access help here.

Hatty Willmoth

My Experience

Over the past year and a half I've lost roughly a sixth of my body weight.

At least, that’s what the scales tell me. Perhaps they’re faulty.

Or maybe I was correct when I first noticed my clothes no longer fit me and theorised that exam stress was reducing my appetite.

Or maybe something else is up. More recently, I’ve had blood test after blood test and a couple of invasive medical procedures in a bid to figure out whether I have a mysterious underlying health condition.

Who knows what’s going on? I don’t.

The point is, it’s probably bad and it’s definitely not deliberate. I was healthy as a size 10 and I didn’t mean to shrink. But that’s what happened.

And it’s confusing because I like it.

Years of socialisation as a woman in a patriarchal society has taught me to believe that I look better and am more acceptable as a human being when I’m taking up less space.

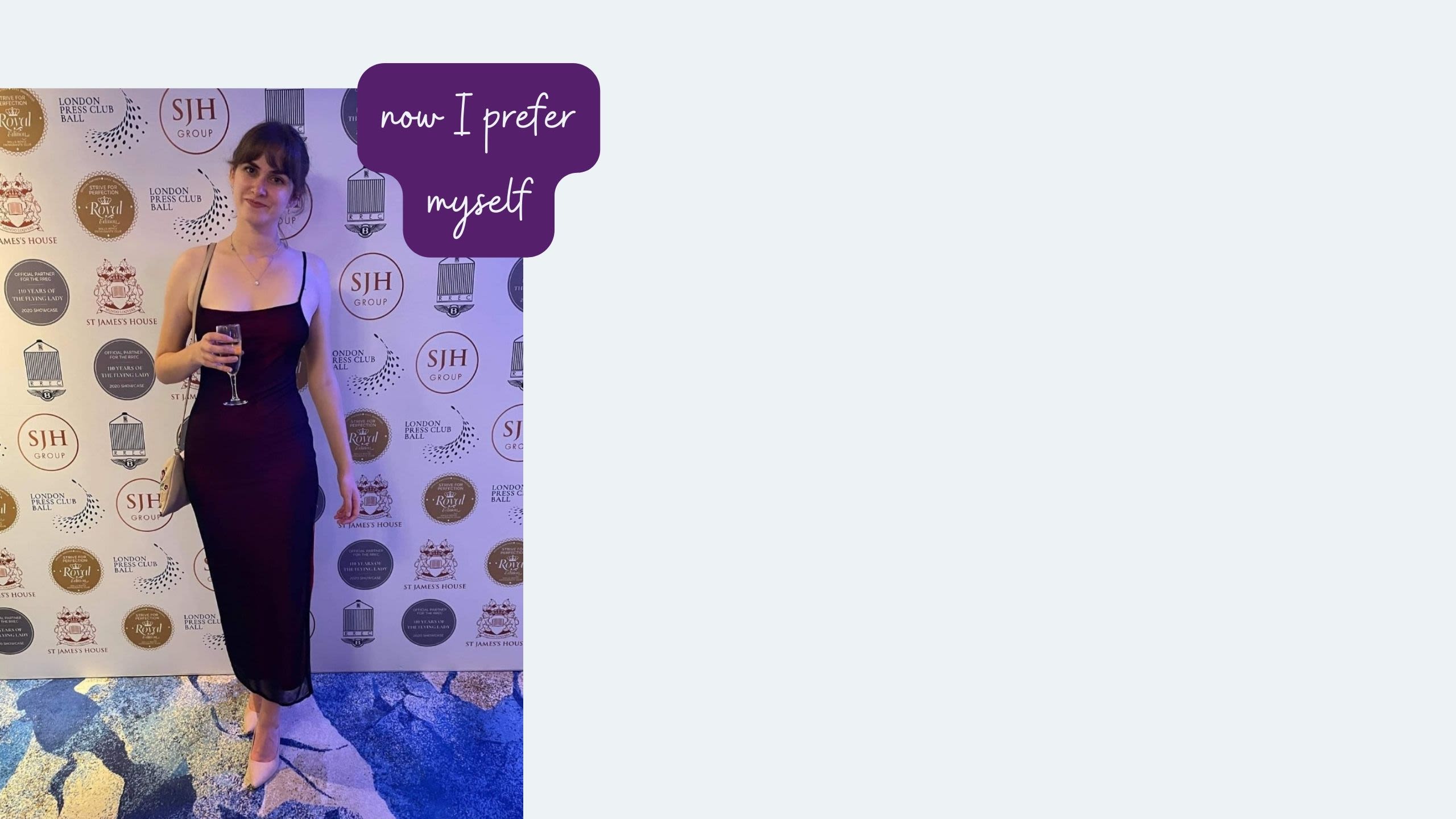

I didn’t love how I looked before. I prefer myself now. But the way that I got here was unhealthy and disorientating.

I shouldn’t be so proud of my 25-inch waist, even though I wanted it when I was bigger, and now I have it I’m glad of it.

After all, what sort of feminist does it make me to be grateful for ill-health just because it made me smaller?

The compliments don’t help. They fuel my problematic fire, reinforcing an instinctual belief that I am better now than I was before.

I know that’s not true. Bigger bodies have no less value than smaller bodies.

I shouldn’t berate my past self for having a little more tummy flab and slightly wibblier thighs.

And I shouldn’t cling onto my current size at the expense of my health.

Body positivity is so necessary. We shouldn’t strive for prescribed perfection in order to feel worthy of love.

We should strive for self-love, self-acceptance and good health in whatever size it appears.

It can be hard to overcome the long-learnt belief that a slimmer body is a better one.

But I’m trying to be the bigger person.

Over the past year and a half I've lost roughly a sixth of my body weight.

At least, that’s what the scales tell me. Perhaps they’re faulty.

Or maybe I was correct when I first noticed my clothes no longer fit me and theorised that exam stress was reducing my appetite.

Or maybe something else is up. More recently, I’ve had blood test after blood test and a couple of invasive medical procedures in a bid to figure out whether I have a mysterious underlying health condition.

Who knows what’s going on? I don’t.

The point is, it’s probably bad and it’s definitely not deliberate. I was healthy as a size 10 and I didn’t mean to shrink. But that’s what happened.

And it’s confusing because I like it.

Years of socialisation as a woman in a patriarchal society has taught me to believe that I look better and am more acceptable as a human being when I’m taking up less space.

I didn’t love how I looked before. I prefer myself now. But the way that I got here was unhealthy and disorientating.

I shouldn’t be so proud of my 25-inch waist, even though I wanted it when I was bigger, and now I have it I’m glad of it.

After all, what sort of feminist does it make me to be grateful for ill-health just because it made me smaller?

The compliments don’t help. They fuel my problematic fire, reinforcing an instinctual belief that I am better now than I was before.

I know that’s not true. Bigger bodies have no less value than smaller bodies.

I shouldn’t berate my past self for having a little more tummy flab and slightly wibblier thighs.

And I shouldn’t cling onto my current size at the expense of my health.

Body positivity is so necessary. We shouldn’t strive for prescribed perfection in order to feel worthy of love.

We should strive for self-love, self-acceptance and good health in whatever size it appears.

It can be hard to overcome the long-learnt belief that a slimmer body is a better one.

But I’m trying to be the bigger person.

Complimenting someone on losing weight has very few benefits.

It is impossible to tell how your comment will interact with that person's own hidden experiences.

Perhaps they have a chronic illness or an eating disorder, or maybe their weight-loss is a bewildering mystery.

In any case, it's not worth it. Weight-loss compliments can do a world of damage.

It's better not to bother.